Live Skype chats played an invaluable role in the disaster response to Haiti but this has gone largely unnoticed by both mainstream and citizen media. I have a Word document with over 2,000 pages worth of Skype chat messages exchanged in various groups during the first 2.5 weeks after the earthquake. I have no doubt that this data will become a source of major interest for scholars seeking to evaluate the disaster response in Haiti.

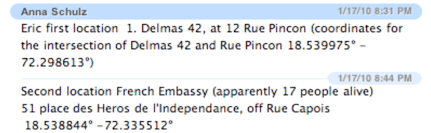

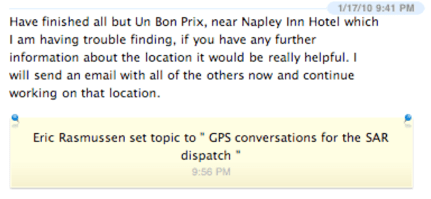

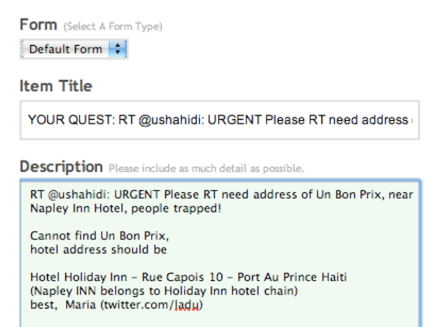

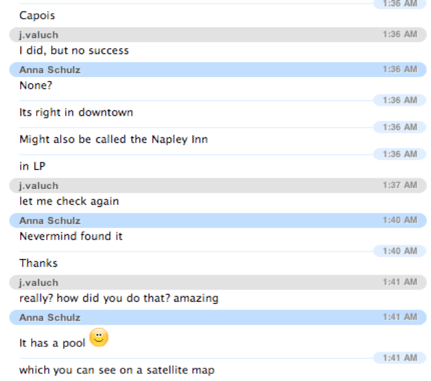

The Skype chats reveal a minute-by-minute account of the actions and decisions that organizations like Ushahidi, FrontlineSMS, InSTEDD, Sahana, Google, Thomson-Reuters and others took following the earthquake. Search and Rescue (SAR) teams in Port-au-Prince also participated in these Skype chats:

For the full story behind the above exchange between Anna, Eric and myself, please see my previous blog post. In addition to SAR staff, the US State Department, a White House liaison contact, SOUTHCOM, DAI, UN/OCHA, WFP, the US Coast Guard, a Telecom company, and so on were all on live Skype chats at one point or another. It’s actually hard to keep track of everyone who has used the various Skype chats since the earthquake.

For the full story behind the above exchange between Anna, Eric and myself, please see my previous blog post. In addition to SAR staff, the US State Department, a White House liaison contact, SOUTHCOM, DAI, UN/OCHA, WFP, the US Coast Guard, a Telecom company, and so on were all on live Skype chats at one point or another. It’s actually hard to keep track of everyone who has used the various Skype chats since the earthquake.

The most active and critical Skype Chat Groups were/are:

- Haiti Tech Ushahidi Situation Room (72 users)

- GPS Conversations for the SAR Dispatch (21 users)

- SMS Logistics (37)

- Ushahidi + US Coast Guard + SOUTHCOM (11 users)

- Urgent Response Group (13 users)

- Ushahidi Volunteer Task Force (168)

I would really like to see a discourse analysis and social network analysis of this data. Not to mention different visualizations of the data. In fact, I’d love to partner with anyone who has the time and expertise in these areas to do this. For now, lets take the first Skype chat group above, which was the most critical group during the first week, and just focus on the growth of this group in terms of users during the first week. And then lets create some Wordl visualizations based on data in this chat group.

I started the Haiti Tech Ushahidi Situation Room a couple hours after David Kobia and I launched the Ushahidi-Haiti platform. The second person I called (on my cell) after David was Chris Blow from Meedan. Chris got started on the icons for the platform right away. In the meantime, we used color-coded dots to represent the different categories/indicators.

I checked in with Chris on Skype a couple hours later. Below is the progression of users added to the Skype chat during the first week in case anyone wants to start on some simple social network analysis:

[1/12/10 9:09:55 PM] Patrick Meier: hey Chris, you there?

[1/12/10 10:00:27 PM] Patrick Meier added Brian Herbert to this chat

[1/12/10 10:02:30 PM] Patrick Meier added David Kobia to this chat

[1/12/10 10:10:39 PM] Patrick Meier added Jeffrey Villaveces to this chat

[1/12/10 10:47:41 PM] Jeffrey Villaveces added Luishernando to this chat

[1/12/10 11:42:01 PM] Jeffrey Villaveces added Gabriel Dicelis to this chat

[1/12/10 11:48:49 PM] Brian Herbert added Ory Okolloh to this chat

[1/13/10 2:00:03 AM] Patrick Meier added Kennedy Kasina to this chat

[1/13/10 2:00:11 AM] Patrick Meier: just added Ken to this chat

[1/13/10 2:00:43 AM] Ory Okolloh added Henry Addo to this chat

[1/13/10 2:02:54 AM] Brian Herbert added Henry Addo to this chat

[1/13/10 3:30:13 AM] Patrick Meier added Kaushal Jhalla to this chat

[1/13/10 8:46:07 AM] Patrick Meier added Claire U to this chat

[1/13/10 10:06:59 AM] Brian Herbert added Pablo Destefanis to this chat

[1/13/10 10:09:41 AM] Brian Herbert added Oscar Salazar to this chat

[1/13/10 10:22:02 AM] Patrick Meier added Emily Jacobi to this chat

[1/13/10 10:47:32 AM] Oscar Salazar added Nicolas et Alice BIais- Bonhomme to this chat

[1/13/10 10:51:59 AM] Patrick Meier added Rob Baker to this chat

[1/13/10 11:22:54 AM] Emily Jacobi added Mark Belinsky to this chat

[1/13/10 12:05:59 PM] Patrick Meier added Josh Marcus to this chat

[1/13/10 12:08:10 PM] Patrick Meier added Shoreh Elhami to this chat

[1/13/10 12:11:54 PM] Jeffrey Villaveces added Luke Beckman to this chat

[1/13/10 12:18:52 PM] Luke Beckman added Eduardo Jezierski, Eric Rasmussen to this chat

[1/13/10 12:38:09 PM] Brian Herbert added Erik Hersman to this chat

[1/13/10 1:29:05 PM] Luke Beckman added Brian Steckler to this chat

[1/13/10 1:41:03 PM] Erik Hersman added Caleb Bell to this chat

[1/13/10 2:32:19 PM] Erik Hersman added Jason Mule to this chat

[1/13/10 2:40:31 PM] Luke Beckman added Josh Nesbit to this chat

[1/13/10 5:32:31 PM] Claire U added Fabienne to this chat

[1/13/10 6:13:48 PM] Eduardo Jezierski added Mark Prutsalis to this chat

[1/13/10 7:28:34 PM] David Kobia added Andrew Turner to this chat

[1/13/10 10:59:49 PM] Josh Marcus added Tim Schwartz to this chat

[1/14/10 12:25:58 AM] Tim Schwartz added Ryan Brown to this chat

[1/14/10 4:00:41 AM] Erik Hersman added Meryn Stol to this chat

[1/14/10 4:25:46 AM] Erik Hersman added Victor Miclovich to this chat

[1/14/10 4:29:46 AM] Kennedy Kasina added Charles Kithika to this chat

[1/14/10 5:02:55 AM] Erik Hersman added Brian Joel Conley to this chat

[1/14/10 5:14:35 AM] Kennedy Kasina added lisudza to this chat

[1/14/10 5:21:03 AM] Erik Hersman added aliveinbaghdad to this chat

[1/14/10 1:26:56 PM] Erik Hersman added Dale Zak to this chat

[1/14/10 1:43:43 PM] Dale Zak added benrigby to this chat

[1/14/10 1:51:00 PM] benrigby added Boris Korsunsky to this chat

[1/14/10 2:00:21 PM] Brian Herbert added Abdallah Chamas to this chat

[1/14/10 3:09:37 PM] Josh Nesbit added Paul Goodman to this chat

[1/14/10 3:24:11 PM] Brian Herbert added Satchit Balsari to this chat

[1/14/10 3:37:02 PM] Satchit Balsari added ritwikdey to this chat

[1/14/10 3:50:38 PM] Satchit Balsari added Selvam Velmurugan to this chat

[1/14/10 4:12:47 PM] Josh Marcus added Sharda Sekaran to this chat

[1/14/10 5:53:19 PM] Ory Okolloh added Jonathan Greenblatt to this chat

[1/14/10 7:30:37 PM] Tim Schwartz added wendell_iii to this chat

[1/14/10 10:02:25 PM] Tim Schwartz added Christopher Csikszentmihalyi to this chat

[1/14/10 11:43:09 PM] Josh Nesbit added Robert Munro to this chat

[1/15/10 4:59:07 AM] Brian Steckler added Ryan Burke to this chat

[1/15/10 5:03:45 AM] Kennedy Kasina added joanwmaina to this chat

[1/15/10 5:39:11 AM] David Kobia added Cooper Quintin to this chat

[1/15/10 10:38:10 AM] mark.prutsalis added Chamindra de Silva to chat

[1/15/10 11:24:43 AM] Sharda Sekaran added Amir Reavis-Bey to this chat

[1/15/10 11:27:07 AM] Josh Nesbit added David Wade to this chat

[1/15/10 3:30:51 PM] Paul Goodman added Tapan Parikh to this chat

[1/15/10 7:02:37 PM] Mark Belinsky added Philip Ashlock to this chat

[1/15/10 8:02:39 PM] Brian Steckler added Michael D. McDonald to chat

[1/15/10 10:15:38 PM] mark.prutsalis added David Bitner to this chat

[1/16/10 12:26:11 PM] mark.prutsalis added lifeeth to this chat

[1/16/10 9:23:24 PM] Rob Baker added Rachel Weidinger to this chat

[1/17/10 11:36:20 AM] Josh Nesbit added Lisa Lamanna to this chat

[1/18/10 3:54:06 PM] Luke Beckman added doshi.sd to this chat

[1/18/10 4:18:09 PM] Tim Schwartz added Christina Xu to this chat

[1/19/10 12:10:19 PM] Jeffrey Villaveces added Amaury to this chat

[1/19/10 6:05:19 PM] Ryan Burke added Randy Maule to this chat

[1/19/10 10:24:21 PM] Tapan Parikh added david.notkin to this chat

Here’s the Wordl rendition of the above text:

Below is the Wordl visualization of all the data in the Haiti Chat group, i.e., not only users being added but also the full content of all the chats between 9pm on January 12th through 9pm on January 30th. This constitutes over 300 pages of content in a Word document. Of course, dates and individual names still come up most frequently.

The Wordl visualization below draws on the first week of data but with all names, dates and times removed. This enables us to focus exclusively on the content or dialogue exchanged between users.

I like the fact that the word “thanks” stands out fairly prominently. Stay tuned for more Wordl visualizations on the other Skype chat groups. In the meantime, if you want to get started on some more statistical discourse analysis or social network analysis, please feel free to get in touch. Thanks!

I like the fact that the word “thanks” stands out fairly prominently. Stay tuned for more Wordl visualizations on the other Skype chat groups. In the meantime, if you want to get started on some more statistical discourse analysis or social network analysis, please feel free to get in touch. Thanks!

Patrick Philippe Meier