When I came across the Whistle Goblins (a.k.a. Whistle Avengers) last month, I had flashbacks to the early days of digital humanitarians (some 15 years ago). The latter were also the most ragtag group of people I’d ever met. They too used crowdsourcing and digital technology (to support humanitarian efforts, starting with their response to the 2010 Haiti Earthquake). They, too, formed strong bonds that spurred many to engage in adjacent social causes, such as human rights projects (e.g., in Syria) and digital activism (e.g., in Russia). Digital humanitarians also got pushback and learned some hard lessons along the way.

Might some of those setbacks and the evolution of digital humanitarians potentially be of value to members of the Whistle Resistance? I don’t know, but maybe it’s worth exploring? Disclaimer: I was one of the many early digital humanitarians and authored the book Digital Humanitarians (Taylor & Francis Press, 2015).

The Sound of Resistance

But first, the Whistle Resistance! Here’s what they’re up to in one (longish) sentence:

These Goblins & Avengers (there are nearly 200 of them) are 3D-printing free whistles at scale (500,000+ in less than 2 months and radically accelerating) and shipping them for free across 49 US states and Puerto Rico (80% of orders go out within 4 days) in response to requests from a wide range of individuals and local communities who use these whistles to alert their neighbors when ICE and Border Patrol are nearby.

(These communities range from a local pet shop in Denver to libraries, community centers, coffee shops, bookstores, and others on the front lines of keeping their neighborhoods safe).

One of the Goblins, Dan, explains that the whistles serve as:

“[An] alert system built entirely at street-level and massively deployed to serve two purposes: bring your neighbors out to witness the abuses of ICE and to let those that are more at risk to know to stay in or to find shelter immediately.”

More from Dan:

“There’s a simple code system that goes along with the whistles: short staccato bursts if ICE is seen in the area and long blows if they’re actively snatching someone (though, honestly, in my experience you just blow like hell).”

Another Goblin, Heidi, who goes by Courtney Milan on Bluesky, notes that 3D-printed whistles allow “people to exercise their First Amendment right to assemble and to redress the government for grievances.” The whistles thus serve to crowdsource the application of the First Amendment, communicate early warnings to those at-risk, and bear witness (from multiple angles) to dispute false narratives. (As an aside, one of the primary technologies used by digital humanitarians of old was Ushahidi, Swahili for “witness”.)

More from Heidi: “While whistles may not stop bullets, they can stop bullies,” by making it clear that we’ll “stand up and we will watch, and we will judge you [bullies] and will remember, and you will [ultimately] not get away with it.”

From Sean, a fellow Goblin on Bluesky:

“Renee Good and Alex Pretti were surrounded by the blasts of whistles, and they’re no longer here.

I print whistles because they make neighbors because they make neighbors come running, ensure enough people are recording, so we can believe our eyes.

But whistles mean more than that. […] many of these whistles will never get blown – but wearing one, handing one out, shows that you’re here for your neighbors.”

Sean, quoting Em, another Goblin on Bluesky: “Even if all I can do in the moment is get someone’s name, that means their family knows what happened to them.”

Never underestimate the collective power of hearing dozens of whistles, not only as deterrence to bullies (think “sousveillance”, there are more of us than you and we’re watching your every move), but also as empowering to witnesses (I am not alone, I have friends everywhere). These activities synchronize action and coordination, which can be a powerful display of resistance.

While there are multiple examples of whistles making a difference, perhaps further proof of their impact can be seen in responses from anti-Avenger types, e.g., they’re literally calling for the banning of whistles and referring to them as weapons: “hearing loss causing machines that terrorists are using against ICE.”

Their Superpower

But what is most striking to me (and equally important as the whistles themselves) is the *very* diverse cross-section of people who make up the Goblin-Avenger network. To quote Dan again, “these people include romance authors and nerdy engineers and crusty old punks and internet weirdos and every other type of person imaginable […].” Heidi, mentioned above, is a former US Supreme Court law clerk.

More from Dan:

“Across the country there are whistle packing parties happening in church basements and bars and nonprofit offices and pretty much anywhere else that can hold some people, some tables, and boxes of whistles, zines, and bags to put them all in.”

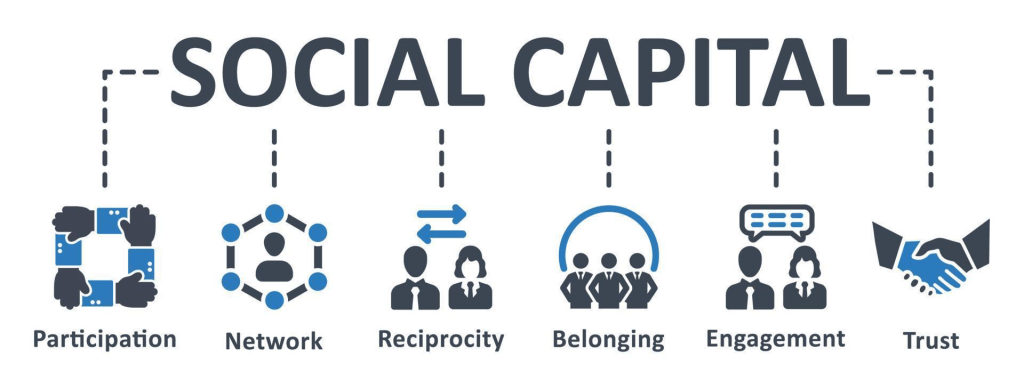

This is ultimately their superpower, i.e., not the technology, not the whistles, but the highly diverse and caring community they’re co-creating with strong social ties and grounded in a set of shared values. This was also the superpower behind digital humanitarians. And if past is prologue, this power will outlive the whistles by a long shot.

The technology, the 3D printers, didn’t all of a sudden decide to spontaneously print whistles. People cared, which is why some turned to 3D printers. It is the human emotion that makes all this possible, from the whistle makers to those brave souls on the frontlines in the streets. From Heidi: “It is the communities that fight fascism. The whistles are just a way to aid communities in becoming communities. And the thing we do is just a tiny part of that.”

Like digital humanitarians of old, who saw a massive earthquake in Haiti in January 2012, and wanted more than anything to find a way to help, to do something, in the case of the Whistle Resistance, “So many people were so upset and they didn’t know what to do, and we could say, here is something you can do,” says Kit, yet another Goblin (one of the romance-writers who goes by Mostly Bree on Bluesky).

The takeaway, here, is that the human act of caring is evenly distributed (across age, gender, birthplace, etc.), hence the diversity we see among Goblins and Avengers. It is a feature, and a vital one. 3D printing technology creates the opportunity to act on our innate human emotions. Technology, in this sense, can extend our humanity, creating the opportunity to display that humanity in 3D. (It can also do the exact opposite, of course. More on that later).

Back to Dan. What he writes below is also an accurate description of the early days of digital humanitarians:

“It’s all so chaotic and loosely organized as to feel like it might fly off the rails at any moment, but impossibly, it hasn’t (thanks in large part to the efforts of a small group of core members). It all runs on a handful of chats that fill with messages so quickly that I think most people put them on mute immediately. It’s all jokes and troubleshooting and moments of real human earnestness shared between folks who don’t even know each others actual names for the most part.”

These very interactions build the social ties and cohesion that can lead to the launch and support of other mutual-aid networks because the social capital has been built through this shared experience around whistles. That’s what I mean by the caring outliving the whistles; about the caring spilling out into other forms of direct nonviolent action.

We saw this time and time again with digital humantiarians. Once they had built the social capital within their networks, and honed their skills in response to earthquakes and other humanitarian crises, they applied them to nonviolent civil resistance, election monitoring, and even to wildlife conservation.

The Multiplier Effect

Like digital humanitarians, the Whistle Resistance is also “regenerative” in that it’s inspiring other goblins to the cause; serving as a springboard for expanded agency:

What’s more, they’re supporting a wide range of other causes.

I didn’t get into the costs of 3D printing, etc., but it should come as no surprise that the Whistle Resistance is using crowdfunding to keep the whistles and shipping free. If you’re new to 3D printing, one key ingredient is filament, pictured below.

Think of filament as the equivalent of ink for regular printers. No ink, no 2D printing. No filament, no 3D printing. So they’re sourcing massive amounts of filament through crowdfunding and partnerships.

(Side note: Remember Ethan Zuckerman’s “Cute Cat Theory of Digital Activism? Think “Cute 3D-printed Cat Theory”. Also, 3D printing has become a critical, high-growth component of specialized US manufacturing, a market valued at some $6 billion and growing rapidly. Cue a light version of Ethan’s “dictator’s dilemma”?)

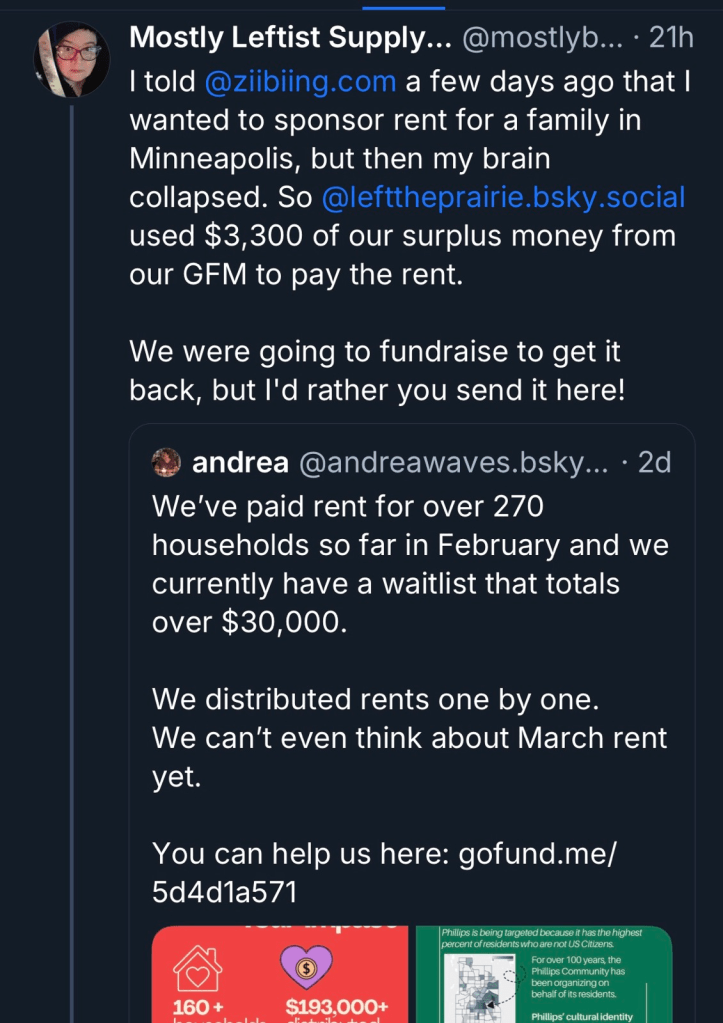

In any case, when the Globlins have funding left over, they put this money to good use, showing additional positive spill-over effects of their 3D-printing bonanza:

As another Bluesky user added, “let’s not assume that all the people […] passing out whistles are doing nothing else. People – ‘wine moms,” “knitters,” who else do you think has ready access to breast milk? – are working behind the scenes for good.” They’re just not “all crowing about it on social media.” Spot on, and let’s not assume that whistle makers are doing nothing else either.

Like Digital Humanitarians

As Whistle Goblins & Avengers will be the first to say, they’re just a ragtag group of people, just like you and me; they’re not special. They simply care and together have demonstrated that yes, we can act. We can help. All of us. Everything else follows from this. This here is from Kit:

These points also reflect the early ethos among digital humanitarians. Digital humanitarians weren’t trained humanitarians; the vast majority had never been engaged in disaster response. They didn’t ask the UN or Red Cross for permission to launch their efforts in the wake of the 2010 Earthquake; they just got it done, and at a speed and with such agility that established humanitarian organizations were simply not designed to match. This sparked quite a pushback against digital humanitarians (including accusations of being “crowd-sorcerers”). Some criticisms were based on misunderstandings, others were driven by ulterior motives, but some criticisms were absolutely valid.

As this post is already long enough, I’ll write a sequel post to share the strong pushback some pro-whistle activists are facing and, more importantly, to humbly consider potential ways forward based on lessons from digital humanitarians.