I’ve written about crisis mapping on this blog and elsewhere so what I want to do here is simply reflect on where we’ve been in the field and on what I’d like to see happening over the coming weeks, months and years. For a “Brief History of Crisis Mapping” click here and for a “Video Primer on Crisis Mapping” please follow this link.

What follows is thus a brief personal account of the field of operational crisis mapping as I have experienced it over the past five years. I also add three (TED) wishes for the future of crisis mapping, which, when fulfilled, should usher in the next logical step in the field, namely Mobile Crisis Mapping (MCM).

I first began thinking about crisis maps in 2003 when consulting for the OSCE on the Environmental Security Initiative (EnvSec), which made extensive use of social mapping to assess environmental security dynamics in Central Asia. I was impressed by the notable added value that the maps brought to that project (particularly at the community level) and wanted to do the same for the field of conflict prevention and early warning.

I therefore toyed around with the idea of “FAST Maps” in 2003 when setting up FAST International’s United Nations (UN) Liaison Office in New York. FAST was one of the leading pioneers of conflict monitoring and early warning analysis. At the time, however, FAST was only producing conflict barometers, or baselines, i.e., time series frequency analysis of conflict (and peace) events. I therefore followed up with a series of proposals on “FAST Maps” sharing them with Jeffrey Sachs at Columbia University’s Earth Institute amongst others.

Here is how I defined FAST Maps back in 2003:

Unfortunately, Swisspeace was unable to secure funding to see this project through, so in 2004 I joined the CEWARN team in the Horn of Africa and set up a GIS Unit in Addis Ababa to map cross-border conflicts in the region. When I left my full time consulting work to pursue my PhD at The Fletcher School, the team in Addis did not have the resources to expand let alone sustain the mapping component of CEWARN.

The main hurdles were threefold: (1) GIS tools were anything but user-friendly and particularly difficult to teach to colleagues who did not have a background in GIS; (2) the cost of the ArcView license was prohibitive; and (3) many in the field of conflict early warning, including donors, still did not get the point of crisis mapping, which meant (amongst other things) that our field monitors in the Horn were never equipped with handheld GPS units, a suggestion I had made in 2005.

In sum, crisis mapping faced a number of hurdles between 2003-2006, but we’ve come a long way since. Although the ideas were being developed as early as 2003, more intuitive and accessible mapping technology was not yet available and an understanding of the value-added of crisis mapping had not fully materialized.

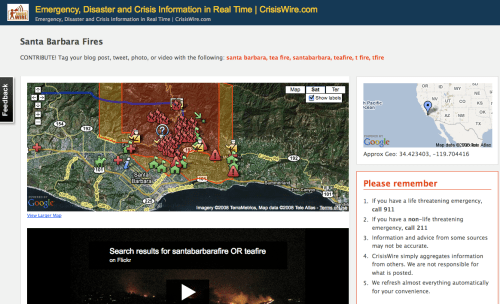

Five years later, crisis mapping is all the buzz, and the technology is finally here to make it happen. The Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) has been engaged in major applied research project on crisis mapping for almost two years. And new donors like Humanity United are excited about the potential of crisis mapping. A new initiative, CrisisMappers, set up by Erik Hersman and myself seeks to facilitate the exchange of best practices and to ensure interoperability across mapping platforms.

Thanks to Google Maps and Google Earth, we’ve moved from static hardcopy maps, to dynamic, interactive and multi-layer digital maps like Ushahidi. OpenLayers and GeoDjango are two recently released tools that further facilitate our efforts.

There is still some way to go, however, at least in terms of the ideas I had back in 2003. So here are my three wishes for the immediate future of crisis mapping:

First wish: we need to think of maps not simply as dynamic tools for improving situational awareness but also as communication tools. The example I’ve used over the past two years:

A local NGO in Somalia encounters a roadblock, they take a picture or video using their camera phone and/or write a quick text message using the format: [town*message] or [lat*long*message]. They send the info to a designated number. Better yet, they have a pre-installed application on their phone (like the iPhone app for Ushahidi) that automatically geo-references and sends the text/picture/video.

Once sent, the text/picture/video gets geo-referenced in real-time on a dedicated Google Maps platform like the SensorWeb.

An icon denoting a security-related event pops up on the map. Anyone monitoring the SensorWeb clicks on the icon, a box opens with the identity (name/picture) of the person who sent the message, the actual message (SMS/video/text), and location.

Within that box are four links: Call, Reply, Broadcast and Tag. Selecting “Call” automatically calls the person back via Skype or similar VoIP tool. Selecting “Reply” or “Broadcast” prompts the user for the preferred mode of communication, i.e, by “SMS” or “Email”. This allows the user to access an address book, select contacts and, for example, to use SMS broadcasting to forward the text (or picture) right back to the field with the option of adding to the text a set of instructions for early response.

The point here is that the user never needs to navigate away from the map, which is what turns the map into a communication tool. The user is at most 3 clicks of the mouse away from facilitating real-time networked communication. Being on the Board of Advisers for Ushahidi and on the SensorWeb team, I hope this is a functionality that both projects will seriously consider and implement.

Second wish: RSS feeds need to be an integral part of mapping platforms, much like they are for Google Reader. If done well, the feeds can automate the process outlined above. For example, local communities should be able to subscribe to Ushahidi in order to receive (and also submit) information via email and/or SMS on specific events, e.g., robbery or to all events within a specific geographic area, say Kibera. This new approach can help us shift away from traditional hierarchical approaches (that characterize the majority of current conflict early warning/response initiatives) and foster a more distributed approach to conflict prevention. For only then will we be able to facilitate the crowdsourcing of information AND response.

Third wish: this has to do with data security and connectivity. In terms of security, Mobile Crisis Mapping (MCM) platforms should integrate encrypted SMS and email communication. Users should also be given the option of remaining anonymous. As for connectivity, future MCM platforms should promote peer-to-peer mobile phone technology that enables mobile phone users to communicate directly between one another without the need for cell phone towers. This technology is currently being developed out of MIT and, in my opinion, has the potential to have even more far reaching consequences in the telephony sector than Napster (file sharing) did in the music industry.

In conclusion, we’ve come a long way since 2003 but there is still plenty to do. We need more creative thinking and innovative applications. As Columbia University Professor Michael Cervieri recently noted in Kenya’s leading national newspaper regarding Ushahidi and the election violence, people in proximity to violent conflict are not going to be sitting at their computers (the very few who have access to computers) waiting to get information, “they are going to run.” This is obvious and why the future of crisis mapping belongs to Mobile Crisis Mapping.

In addition, future Mobile Crisis Mapping platforms should use spiders to craw the web (newswires and blogs) to populate the map in addition to having individuals in the field adding relevant information to the map. We need both. For the automated feeds, I’m thinking of an approach similar to Havaria and HealthMap which I’ve written about here.

I am relying on the Ushahidi team to help pave the way forward and to continue pioneering the field of Mobile Crisis Mapping over the next few months and years. At the same time, I will rely on the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) to help develop the field of Crisis Mapping Analytics (CMA) in collaboration with Ushahidi and partners. In sum, the future of Crisis Mapping = Mobile Technology + Crisis Mapping Analytics = Mobile Crisis Mapping.

Patrick Philippe Meier