I’m in Mumbai for the next 10 days to work on a flood early warning and response project. Here’s a quick overview of the project:

The Monsoon Project

In Mumbai and Ahmedabad, we will see what kind of qualitative data people have reported. The next step is to to expand the data collection exercise to discreet objective data points that may expedite rescue and response in real-time. Can farmers sitting atop roofs in the flooded villages of Orissa use their cell phones to transmit simple, discreet, data points that would help plot a real-time map of events as they unfold? Can such a platform be created? How far are we in terms of technology and collaboration? At HHI, the Crisis Mapping Project is well underway, with small projects at multiple locations in different stages of development.

The Monsoon project is one such: To pilot such an interactive platform we need a predictable, controlled model within which to test such an instrument. In recent years, the monsoons in Mumbai have invariably brought the city to a stand-still. What we want to do now is to see if we can develop simple indicators that the common man can identify (“early warning signs”) to alert their communities to an impending “bad-floods day” in Mumbai. This monsoon Gregg Greenough and Patrick Meier from HHI will be in Mumbai to meet with the faculty at the Geography Dept of Mumbai University to explore ways to collaborate on developing these indicators. Site visits in Mumbai before and after the workshop.

Action points: Request MU/ AIDMI / CEE to identify local partners in India that should be invited to the workshop. Once the indicators are identified, the goal is to test the technology on a local platform, amongst pre-selected volunteers across the city, during the monsoons of 2009.

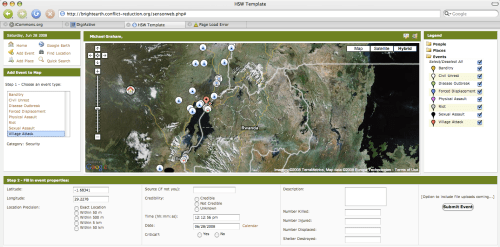

My role, as part of the HHI team, is simply to provide a conceptual and technical overview of other crisis early warning projects that make use of mobile technologies. For example, I got the green light from Ory Okolloh to consider a potential partnership with the team in Mumbai should making use of the Ushahidi platform make sense for the Monsoon Project. (Incidentally, congratulations to the Ushahidi team on launching their most recent version of the platform!) In addition to Ushahidi and a number of other related initiatives, I will share the latest maps of Bihar on Google Earth to stimulate a dialogue on whether this type of dynamic mapping is operationally useful (the map I’ve linked to here is not particularly impressive). In conclusion, I will share relevant best practices and lessons “learned” in the field of early warning and response.

It may not be a coincidence that the National Geographic channel was just featuring a documentary on the great Mumbai floods of July 2005 yesterday. Watching these pictures and those of Bihar over the past two weeks, I’m starting to get some sense of the challenge ahead, not least because the topic of disaster management is an area I have more academic than practical experience in; so I’ll be doing a lot of listening and learning. Before leaving for Mumbai, I had the opportunity to touch base with a friend at the Fletcher School who just returned from working on flood preparedness and response in Bihar.

In any case, I wanted to share some of my own observations. The government’s response to the devastation in the northeast of the country has been particularly slow, with just one military helicopter spotted once or twice in two weeks, according to a BBC report I saw yesterday.

If we are to make good on the UNISDR’s call for a shift towards people-centered early warning, then flood early warning/response systems ought to empower local communities to get out of harm’s way and minimize loss of livelihood. This shift in discourse and operational mandate is an important one in my opinion. Centralized, state-centered, top-down, external responses to crises are apparently increasingly ineffective.

In the case of the devastating floods of 2005, part of the problem was the late warning. The rains had already begun when India’s meteorological department realized that unlike monsoon storms, this storm had clouds as tall as 15 kilometers as opposed to the usual 8 kilometers. Even if the warning had been disseminated hours or even days earlier, would the most vulnerable populations in Mumbai have had the capacity to get out of harm’s way? I don’t know what the Indian government’s operational plans look like for this type of disaster, but I hope to learn soon.

Another question on my mind is if/how mobile technology might empower vulnerable communities in Mumbai during the Monsoon season? As it happens, the front page of today’s (Sunday print edition) of The Times of India figured an article on mobile phones: “A Mobile in Every Hand by 2020.” I include some sections below:

Today, one in four Indians has a mobile phone. […] From the villager sitting atop his half-drowned hut calling for help in flood-hit Bihar, to the kabadiwallah who eagerly hands you his number, it’s mobile networking like never before.

“[…] the mobile phone’s ‘greatest impact [will] be on those people with professions that are time, location and information sensitive. […] fishermen wanting a weather update or the location of the best catch; hospitals contacting patients without a permanent address; SMSes on the Sensex.”

“It is true that network coverage and mobile penetration are still limited to certain areas. But, interestingly, as a study by the Center for Knowledge Societies (CKS) showed in Maharashtra, Up and Karnataka, many new mobile users belong to poorer areas with scarce infrastructure, high levels of illiteracy and low PC and internet penetration.”

I remember an interesting conversation I had last year with Suha Ulgen, the coordinator of the UN Geographic Information Working Group Secretariat (UNGIWIG), regarding an earthquake preparedness and response project he had worked on in Turkey. The team involved in the project used mobile technologies and GPS units to map the most vulnerable areas (e.g., buildings, bridges, etc) in various neighborhoods across the city. Together with local volunteers, they documented the neighborhoods in great detail during the day, and would upload all their data directly on to a dynamic mapping platform in the evenings.

This approach appeals to me for several reasons. First, the approach comes close to local crowdsourcing. Tapping into local knowledge is critical. As mentioned in this article (PDF) I wrote for Monday Developments (April/2007), “From Disaster to Conflict Early Warning: A People-Centered Approach,” the non-local community (a.k.a. international community) has a lot to learn when it comes indigenous early warning and response practices:

In Swaziland, for example, we are taught floods can be predicted from the height of bird nests near rivers, while moth numbers predict drought. Because these indicators are informal, they rarely figure in peer-reviewed journals and remain invisible to the international humanitarian community.

I’m looking forward to learning more about the corresponding local know how in Mumbai. Second, vulnerability mapping is an important component of preparedness training, contingency planning and disaster response. Third, geo-referencing pockets of vulnerability using a dynamic platform provides a host of new possibilities for disaster response including automated and subscription-based SMS alerts, rapid disaster impact assessments and more networked forms of communication in crisis zones. In addition to mapping areas of vulnerability, one could also map potential shelter areas, sources of clean water, etc.

This may or may not make sense within the context of flooding and/or Mumbai, which is why I’ll definitely be doing a lot of listening and learning in the coming days. Any feedback and guidance in the meantime would certainly be of value.

Patrick Philippe Meier