Traditional conflict analysis indicators have ranged from low per capita GNI and ethnic diversity to high youth unemployment and restricted political rights. These indicators are generally drawn from government statistics, which are rarely updated more than once a year. This national-level data is useful for understanding “why, when and how conflict originate,” but the data is actually “less useful in explaining or predicting when or how violent interactions will occur…” (1).

In other words, recognizing patterns in structural data is inherently difficult since the aggregate nature of such data means that intra-annual and sub-national data variation is particularly muted. In sum, one cannot solely rely on the statistics produced by leading international development agencies to monitor potential for conflict escalation.

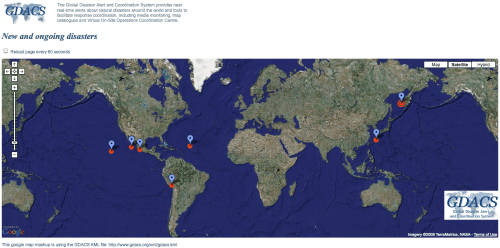

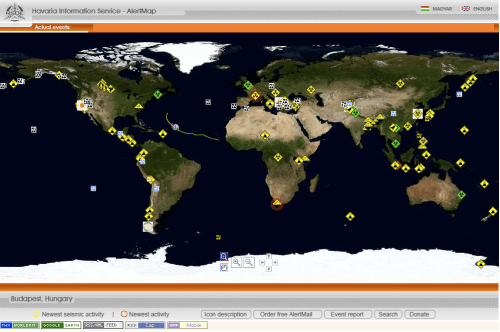

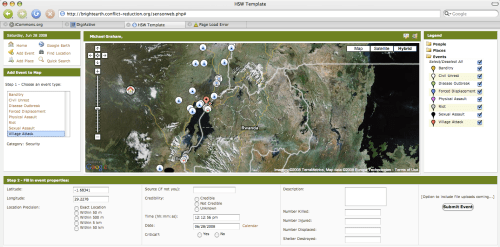

Location, location, location. The purpose of crisis mapping is to shift away from structural and tabular conflict analysis towards more dynamic, real-time and geo-referenced modeling. Think of Serious Gaming such as “A Force More Powerful” or “Food Force” only with real spatial data on real actors and in quasi-real time—a.k.a. reality mining.

“Reality Mining” is a relatively new concept pioneered by MIT.

[The term] defines the collection of machine-sensed environmental data pertaining to human social behavior. This new paradigm of data mining makes possible the modeling of conversation context, proximity sensing, and temporospatial location throughout large communities of individuals. Mobile phones (and similarly innocuous devices) are used for data collection, opening social network analysis to new methods of empirical stochastic modeling.

This approach facilitates in-situ pattern recognition and simulation by capturing “the view from below,” which means we need to rethink what constitutes an indicator since the underlying data sets required are not readily available. However, the recent study, “Tracking Genocide using Remote Sensing,” shows the untapped potential of remote sensing technology and data to identify patterns in humanitarian crises.

An analogy worth noting here is the field of earthquake physics. Geophysicists have long struggled to predict the place and time of major earthquakes by drawing on seismic data, rock composition and fault lines. A few weeks ago, however, NASA scientists revealed that they could be on the verge of a break through in their efforts to forecast conflict.

Researchers say they have found a close link between electrical disturbances on the edge of our atmosphere and impending quakes on the ground below. Just such a signal was spotted in the days leading up to the recent devastating event in China.

Of course, human behavior and social systems are also highly complex systems. But we are creatures of habit and conditioned by social norms, or patterns. Tactics employed by perpetrators are none other than patterns. If violence is organized, there is pattern. Just this month, the journal Nature published findings from a research project that drew on mobile phone data from 100,000 individuals in a European country “and found that most follow very predictable routines. Knowing those routines means that you can set probabilities for them, and track how they change” (2).

Clearly, accessing mobile phone data in conflict zones is not presently feasible, and may not be for a while. However, location-aware social networking technology may provide new data not heretofore available. Remote sensing and GIS data may also capture proxy indicators that reveal underlying patterns and their associated probabilities in future conflict situations. The point is that as new consumer-based location-aware information communication technologies become more widespread, new data sets may become available. Besides, as the Tracking Genocide study evidently shows, geo-referenced, time-stamped data sets already exists.

Making sense of this data is admittedly no small feat. But initiatives such as Sense Networks, a new software company in New York, is seeking to do just that. The company recently released Macrosense, “a tool that applies complex statistical algorithms to sift through the growing heaps of data about location and to make predictions or recommendations on various questions…” (3). We’re note quite there yet vis-a-vis conflict analysis, but the concept of crisis mapping is becoming increasingly talked about in the humanitarian technology community. Crisis mapping is also gaining donor attention, as evidenced by the momentum behind Ushahidi.

The new field of Crisis Mapping Analytics (CMA) is in its infancy and requires a strong academic base, such as Harvard University, to serve as an incubator. Ultimately, the success of CMA resides on whether or not this methodology is more effective in galvanizing early and effective response, both top-town and bottom-up. Moreover, prediction alone will rarely ensure effective response. Just like disaster management in the case of earthquakes, preparedness and contingency planning at the local level will continue to be key for crisis response to save lives.

Patrick Philippe Meier