Update: Public version of Libya Crisis Map now available:

We activated the Standby Volunteer Task Force (SBTF) on March 1st and quickly launched a Crisis Map of Libya to support humanitarian preparedness opera-tions. This is the largest deployment of the Task Force since it was formed at the 2010 International Conference on Crisis Mapping in Boston (ICCM 2010). Task Force partners include CrisisMappers, CrisisCommons, Humanity Road, ICT4Peace, Open Street Map and MapAction. The Task Force currently has trained 166 volunteers. I’m amazed at how far we’ve come since the response to the Haiti earthquake.

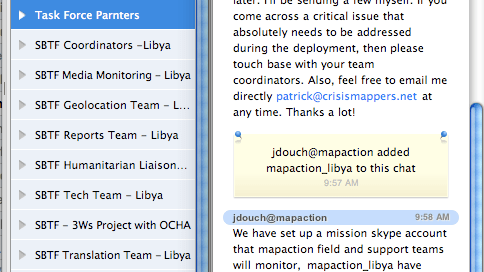

Crisis mapping Libya is definitely no Haiti, for many reasons. The first is that unlike Haiti, we didn’t have to recruit crisis mapping volunteers from scratch. We didn’t have to spend a third of our time training volunteers. We didn’t have to develop new work flows and protocols from thin air. All we had to do was activate the Standby Task Force and everyone knew what to do, like set up dedicated Skype chats (communicating via email is too slow in these scenarios, networked communication is the way to go). Our volunteer CrisisMappers had already been trained and had even participated in an official UN crisis simulation exercise with OCHA in Colombia a few months earlier.

The second reason why this is no Haiti is because the request for activation of the Standby Task Force to provide live crisis mapping support came directly from the UN OCHA’s Information Management unit in Geneva. This was not the case in Haiti since there was no precedent for the crisis mapping efforts we launched at the time. We did not have buy in from the humanitarian community and the latter was reluctant to draw on anything other than official sources of information. Crowdsourcing and social media were unchartered territories. OCHA also reached out to CrisisCommons and OpenStreetMap and we are all working together more closely than ever before.

Contrast this to the case of Libya this week which saw an established humanitarian organization specifically request a volunteer technical community for a live map of reports generated from Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, YouTube and mainstream media sources. Seriously, I have never been more impressed by the humanitarian community than I am today. The pro-active approach they have taken and their constructive engagement is absolutely remarkable. This is truly spectacular and the group deserve very high praise.

From the official annoucement:

OCHA, UNOSAT and NetHope have been collaborating with the Volunteer Technical Community (VTC) specifically including the CrisisMappers, Crisis Commons, Open Street Map, and the Google Crisis Response Team over the past week. The CrisisMappers Standby Task Force has been undertaking a mapping of social media and new reports from within Libya and along the borders at the request of OCHA. As well, the Task Force is aiding in the collection and mapping of 3W information for the response. UNOSAT is kindly hosting the Common Operational Datasets to be used during the emergency (http://www.unitar.org/unosat/libya). Interaction with these groups is being coordinated by OCHA’s Information Services Section. Focal Point: Andrej Verity [verity@un.org].

The third reason this is no Haiti is because we are creating a live map of a hostile situation still unfolding. Haiti provided a permissive environment, politically and geographically. Libya couldn’t be more different. We experienced the serious challenges of crisis mapping a hostile environment when we created a crisis map of Khartoum at the request of local Sudanese activists. This was a stressful deployment but one that was able to provide an important window into what was happening in Khartoum.

In the case of Libya, our humanitarian partner requested that the crisis map be password protected. We intend to make the map public after this phase of the humanitarian operations is over. In the meantime, the screenshots below provide a good picture of what the platform looks like. In the first 48 hours since the activation of the Task Force, over 220 individual reports have been mapped, many including pictures and some with video footage.

We also pulled in the data from the Google Map created by @Arasmus to complement our own live mapping:

None of the above would be possible without such a dedicated network of skilled crisis mapping volunteers. They are truly outstanding and a testament to what civic engagement can do online from thousands of miles away. There’s no doubt that our approach can still be improved. But there’s equally no doubt that all the learning we did in Haiti, Chile and Pakistan went beyond just recommendations but were actually put into practice in a big way thanks to the Task Force.

The Task Force has over 160 volunteers from 18 different countries. Do you want to become one of those crisis mappers? If so, please send an email to join@standbytaskforce.com and we’ll train you on how to become a real pro in crisis mapping.