The following is a presentation that I recently gave at the 2014 Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems Conference (RPAS 2014) held in Brussels, Belgium. The case studies on the Philippines and Haiti are also featured in my upcoming book on “Digital Humanitarians: How Big Data is Changing the Face of Humanitarian Response.” The book is slated to be published in January/February 2015.

Good afternoon and many thanks to Peter van Blyenburgh for the kind invitation to speak on the role of UAVs in humanitarian contexts beyond the European region. I’m speaking today on behalf of the Humanitarian UAV Network, which brings together seasoned humanitarian professionals with UAV experts to facilitate the use of UAVs in humanitarian settings. I’ll be saying more about the Humanitarian UAV Network (UAViators, pronounced “way-viators”) at the end of my talk.

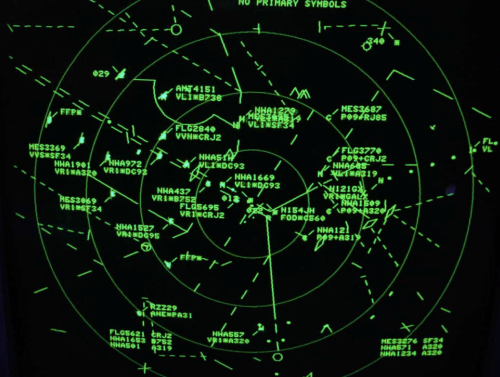

The view from above is key for humanitarian response. Indeed, satellite imagery has played an important role in relief operations since Hurricane Mitch in 1998. And the Indian Ocean Tsunami was the first to be captured from space as the way was still propagating. Some 650 images were produced using data from 15 different sensors. During the immediate aftermath of the Tsunami, satellite images were used at headquarters to assess the extent of the emergency. Later, satellite images were used in the field directly, distributed by the Humanitarian Information Center (HIC) and others to support and coordinate relief efforts.

Satellites do present certain limitations, of course. These include cost, the time needed to acquire images, cloud cover, licensing issues and so on. In any event, two years after the Tsunami, an earlier iteration of the UN’s DRC Mission (MONUC) was supported by a European force (EUFOR), which used 4 Belgian UAVs. But I won’t be speaking about this type of UAV. For a variety of reasons, particularly affordability, ease of transport, regulatory concerns, and community engagement, UAVs used in humanitarian response are smaller systems or micro-UAVs that weigh just a few kilograms, such as one fixed-wing displayed below.

The World Food Program’s UAVs were designed and built at the University of Torino “way back” in 2007. But they’ve been grounded until this year due to lack of legislation in Italy.

In June 2014, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) purchased a small quadcopter for use in humanitarian response and advocacy. Incidentally, OCHA is on the Advisory Board of the Humanitarian UAV Network, or UAViators.

Now, there are many uses cases for the operation of UAVs in humanitarian settings (those listed above are only a subset). All of you here at RPAS 2014 are already very familiar with these applications. So let me jump directly to real world case studies from the Philippines and Haiti.

Typhoon Haiyan, or Yolanda as it was known locally, was the most powerful Typhoon in recorded human history to make landfall. The impact was absolutely devastated. I joined UN/OCHA in the Philippines following the Typhoon and was struck by how many UAV projects were being launched. What follows is just a few of said projects.

Danoffice IT, a company based in Lausanne, Switzerland, used the Sky-Watch Huginn X1 Quadcopter to support the humanitarian response in Tacloban. The rotary-wing UAV was used to identify where NGOs could set up camp. Later on, the UAV was used to support a range of additional tasks such as identifying which roads were passable for transportation/logistics. The quadcopter was also flown up the coast to assess the damage from the storm surge and flooding and to determine which villages had been most affected. This served to speed up the relief efforts and made the response more targeted vis-a-vis the provision of resources and assistance. Danoffice IT is also on the Board of the Humanitarian UAV Network (UAViators).

A second UAV project was carried out by local UAV start-up called CorePhil DSI. The team used an eBee to capture aerial imagery of downtown Tacloban, one of the areas hardest-hit by Typhoon Yolanda. They captured 22 Gigabytes of imagery and shared this with the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) who are also on the Board of UAViators. HOT subsequently crowdsourced the tracing of this imagery (and satellite imagery) to create the most detailed and up-to-date maps of the area. These maps were shared with and used by multiple humanitarian organizations as well as the Filipino Government.

In a third project, the Swiss humanitarian organization Medair partnered with Drone Adventures to create a detailed set of 2D maps and 3D terrain models of the disaster-affected areas in which Medair works. These images were used to inform the humanitarian organization’s recovery and reconstruction programs. To be sure, Medair used the maps and models of Tacloban and Leyte to assist in assessing where the greatest need was and what level of assistance should be given to affected families as they continued to recover. Having these accurate aerial images of the affected areas allowed the Swiss organization to address the needs of individual households and—equally importantly—to advocate on their behalf when necessary.

Drone Adventures also flew their fixed-wing UAVs (eBee’s) over Dulag, just north of Leyte, where more than 80% of homes and croplands were destroyed during the Typhoon. Medair is providing both materials and expertise to help build new shelters in Dulag. So the aerial imagery is proving invaluable to identify just how much material is needed and where. The captured imagery is also enabling community members themselves to better understand both where the greatest needs are an also what the potential solutions might be.

The partners are also committed to Open Data. The imagery captured was made available online and for free, enabling community leaders and humanitarian organizations to use the information to coordinate other reconstruction efforts. In addition, Drone Adventures and Medair presented locally-printed maps to community leaders within 24 hours of flying the UAVs. Some of these maps were printed on rollable, water proof banners, which make them more durable when used in the field.

In yet another UAV project, the local Filipino start-up SkyEye Inc partnered with the University of the Philippines in Manila to develop expendable UAVs or xUAVs. The purpose of this initiative is to empower grassroots communities to deploy their own low-cost xUAVs and thus support locally-deployed response efforts. The team has trained 4 out of 5 teams across the Philippines to locally deploy UAVs in preparation for the next Typhoon season. In so doing, they are also transferring math, science and engineering skills to local communities. It is worth noting that community perceptions of UAVs in the Philippines and elsewhere has always been very positive. Indeed, local communities perceive small UAVs as toys more than anything else.

SkyEye worked with this group from the University of Hawaii to create disaster risk reduction models of flood-prone areas.

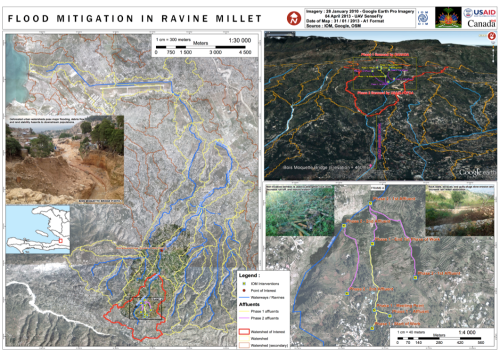

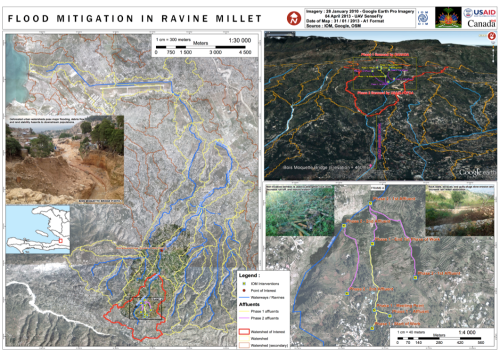

Moving to Haiti, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has partnered with Drone Adventures and other to produce accurate topographical and 3D maps of disaster prone areas in the Philippines. These aerial images have been used to inform disaster risk reduction and community resilience programs. The UAVs have also enabled IOM to assess destroyed houses and other types of damage caused by floods and droughts. In addition, UAVs have been used to monitor IDP camps, helping aid workers identify when shelters are empty and thus ready to be closed. Furthermore, the high resolution aerial imagery has been used to support a census survey of public building, shelters, hospitals as well as schools.

After Hurricane Sandy, for example, aerial imagery enabled IOM to very rapidly assess how many houses had collapsed near Rivière Grise and how many people were affected by the flooding. The aerial imagery was also used to identify areas of standing water where mosquitos and epidemics could easily thrive. Throughout their work with UAVs, IOM has stressed that regular community engagement has been critical for the successful use of UAVs. Indeed, informing local communities of the aerial mapping projects and explaining how the collected information is to be used is imperative. Local capacity building is also paramount, which is why Drone Adventures has trained a local team of Haitians to locally deploy and maintain their own eBee UAV.

The pictures above and below are some of the information products produced by IOM and Drone Adventures. The 3D model above was used to model flood risk in the area and to inform subsequent disaster risk reduction projects.

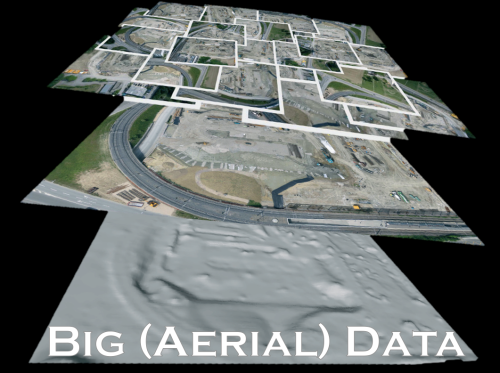

Several colleagues of mine have already noted that aerial imagery presents a Big Data challenge. This means that humanitarian organizations and others will need to use advanced computing (human computing and machine computing) to make sense of Big (Aerial) Data.

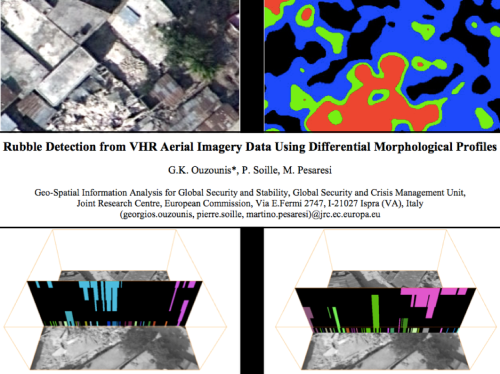

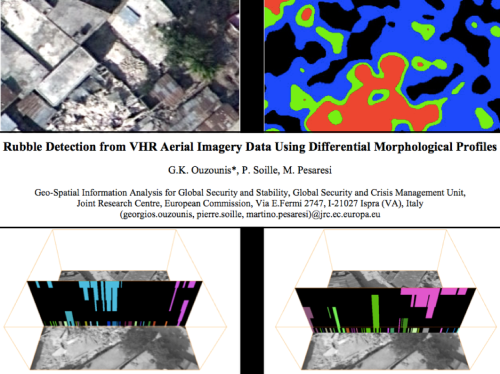

My colleagues at the European Commission’s Joint Research Center (JRC) are already beginning to apply advanced computing to automatically analyze aerial imagery. In the example from Haiti below, the JRC deployed a machine learning classifier to automatically identify rubble left over from the massive earthquake that struck Port-au-Prince in 2010. Their classifier had an impressive accuracy of 92%, “suggesting that the method in its simplest form is sufficiently reliable for rapid damage assessment.”

Human computing (or crowdsourcing) can also be used to make sense of Big Data. My team and I at QCRI have partnered with the UN (OCHA) to create the MicroMappers platform, which is a free and open-source tool to make sense of large datasets created during disasters, like aerial data. We have access to thousands of digital volunteers who can rapidly tag and trace aerial imagery; the resulting analysis of this tagging/tracing can be used to increase the situational awareness of humanitarian organizations in the field.

Digital volunteers can trace features of interest such as shelters without roofs. Our plan is to subsequently use these traced features as training data to develop machine learning classifiers that can automatically identify these features in future aerial images. We’re also exploring the second use-case depicted below, ie, the rapid transcription of imagery, which can then be automatically geo-tagged and added to a crisis map.

The increasing use of UAVs during humanitarian disasters is why UAViators, the Humanitarian UAV Network, was launched. Recall the relief operations in response to Typhoon Yolanda; an unprecedented number of UAV projects were in operation. But most operators didn’t know about each other, so they were not coordinating flights let alone sharing imagery with local communities. Since the launch of UAViators, we’ve developed the first ever Code of Conduct for the use of UAVs in humanitarian settings, which includes guidelines on data protection and privacy. We have also drafted an Operational Check-List to educate those who are new to humanitarian UAVs. We are now in the process of carrying out a comprehensive evaluation of UAV models along with cameras, sensors, payload mechanism and image processing software. The purpose of this evaluation is to identify which are the best fit for use by humanitarians in the field. Since the UN and others are looking for training and certification programs, we are actively seeking partners to provide these services.

The above goals are all for the medium to long term. More immediately, UAViators is working to educate humanitarian organizations on both the opportunities and challenges of using UAVs in humanitarian settings. UAViators is also working to facilitate the coordinate UAV flights during major disasters, enabling operators to share their flight plans and contact details with each other via the UAViators website. We are also planning to set up an SMS service to enable direct communication between operators and others in the field during UAV flights. Lastly, we are developing an online map for operators to easily share the imagery/videos they are collecting during relief efforts.

Data collection (imagery capture) is certainly not the only use case for UAVs in humanitarian contexts. The transportation of payloads may play an increasingly important role in the future. To be sure, my colleagues at UNICEF are actively exploring this with a number of partners in Africa.

Other sensors also present additional opportunities for the use of UAVs in relief efforts. Sensors can be used to assess the impact of disasters on communication infrastructure, such as cell phone towers, for example. Groups are also looking into the use of UAVs to provide temporary communication infrastructure (“aerial cell phone towers”) following major disasters.

The need for Sense and Avoid systems (a.k.a. Detection & Avoid solutions) has been highlighted in almost every other presentation given at RPAS 2014. We really need this new technology earlier rather than later (and that’s a major understatement). At the same time, it is important to emphasize that the main added value of UAVs in humanitarian settings is to capture imagery of areas that are overlooked or ignored by mainstream humanitarian relief operations; that is, of areas that are partially or completely disconnected logistically. By definition, disaster-affected communities in these areas are likely to be more vulnerable than others in urban areas. In addition, the airspaces in these disconnected regions are not complex airspaces and thus present fewer challenges around safety and coordination, for example.

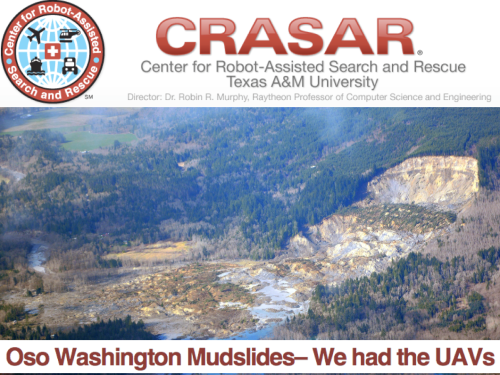

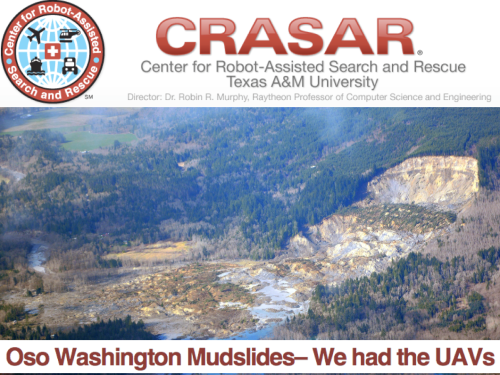

UAVs were ready to go following the mudslides in Oso, Washington back in March of this year. The UAVs were going to be used to look for survivors but the birds were not allowed to fly. The decision to ground UAVs and bar them from supporting relief and rescue efforts will become increasingly untenable when lives are at stake. I genuinely applaud the principle of proportionality applied by the EU and respective RPAS Associations vis-a-vis risks and regulations, but there is one very important variable missing in the proportionality equation: social benefit. Indeed, the cost benefit calculus of UAV risk & regulation in the context of humanitarian use must include the expected benefit of lives saved and suffering alleviated. Let me repeat this to make sure I’m crystal clear: risks must be weighed against potential lives saved.

At the end of the day, the humanitarian context is different from precision agriculture or other commercial applications of UAVs such as film making. The latter have no relation to the Humanitarian Imperative. Having over-regulation stand in the way of humanitarian principles will simply become untenable. At the same time, the principle of Do No Harm must absolutely be upheld, which is why it features prominently in the Humanitarian UAV Network’s Code of Conduct. In sum, like the Do No Harm principle, the cost benefit analysis of proportionality must include potential or expected benefits as part of the calculus.

To conclude, a new (forthcoming) policy brief by the UN (OCHA) publicly calls on humanitarian organizations to support initiatives like the Humanitarian UAV Network. This is an important, public endorsement of our work thus far. But we also need support from non-humanitarian organizations like those you represent in this room. For example, we need clarity on existing legislation. Our partners like the UN need to have access to the latest laws by country to inform their use of UAVs following major disasters. We really need your help on this; and we also need your help in identifying which UAVs and related technologies are likely to be a good fit for humanitarians in the field. So if you have some ideas, then please find me during the break, I’d really like to speak with you, thank you!

See Also:

- Crisis Map of UAV/Aerial Videos for Disaster Response [link]

- How UAVs are Making a Difference in Disaster Response [link]

- Humanitarians Using UAVs for Post Disaster Recovery [link]

- Grassroots UAVs for Disaster Response [link]

- Using UAVs for Search & Rescue [link]

- Debrief: UAV/Drone Search & Rescue Challenge [link]

- Crowdsourcing Analysis of UAV Imagery for Search/Rescue [link]

- Check-List for Flying UAVs in Humanitarian Settings [link]

Picture Credits:

- Danoffice IT; Drone Adventures, SkyEye, JRC