Guest blog post: Bart Stidham is an enterprise architect committed to bringing positive change to the world via better information systems architecture. He has served as CTO of four companies including one of the largest communications companies in the world, been a senior executive at Accenture, and served as CIO of the largest NGO funded by USAID. He is an independent consultant and can be found in Washington, DC when he is not traveling.

This blog post builds off of and supports Patrick Meier’s previous post on developing an SMS Code of Conduct for Humanitarian Response. Patrick raises many important issues in his post and it is clear that with the success of Ushahidi-Haiti it is likely we will see a vast increase in the use of similar SMS based information management systems in the future. While the deployment of such systems and all communications systems is likely to be orderly and well structured in normal circumstances, it is likely that during crises such order may break down and these systems may negatively impact one another. For this reason I applaud Patrick’s effort to raise this issue but my hope is that the “normal order” imposed by governments and societies will help prevent the potential disruption of communications systems from occurring in disasters, emergencies, and crises.

I believe Patrick’s concerns are best discussed in the larger issue of frequency spectrum management. This is a huge issue and one that needs substantial education within the entire response space. It is a growing problem across each and every communications system not just in crises but also globally as we humans desire to communicate more in more ways and with more devices. There are limits to the amount of information that can be “pushed” through any communications system and those limits increasingly have to do with the laws of physics, not just the design of the systems.

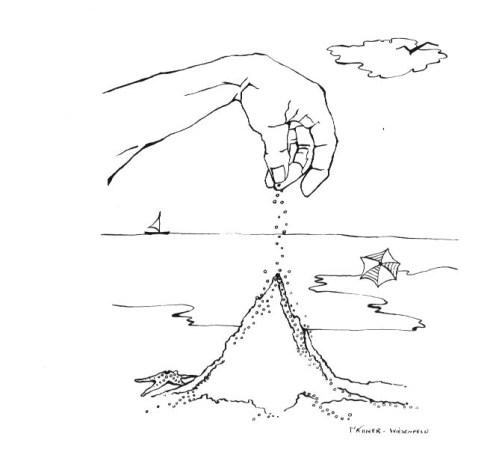

The electromagnetic frequency spectrum (EF) is the basis of all wireless communication. We started our use of it the late 1800s with the first use of radio. Long ago we exhausted the entire spectrum and are now trying to find ways to reuse parts of it more efficiently. However it is critical that we protect this “public commons” on which so many of our communications systems depend.

Every communications system needs a “physical channel” and this varies widely but they all share some common characteristics. One is the problem of “collisions” which are bad because that means that the information is not delivered successfully. As humans using the physical channel of sound and speech we encounter this in our normal conversations whenever we meet in groups. A simple example of a collision is when two or more people are talking loudly over each other with the result being that no one understands what either is saying.

There are multiple ways to deal with collisions and every communications system must manage collisions or the system collapses. One way is to have a token and you are only allowed to talk if you hold the token. This method of managing communications was used brilliantly by various Native American tribes when discussing heated issues such as war – if you are not in possession of the peace pipe (the token) you are not allowed to speak. This forces everyone to listen to what you are saying and to politely take turns speaking. It is passed back and forth and everyone gets a turn. There are several types of network architecture that use this exact method for avoiding collisions.

Another method is collision avoidance by assigning each speaker a window of time to speak in. This is roughly the approach used by GSM for instance. Yet another method is collision detection where you allow for a certain statistical overlap and all parties know that the last “conversation” collided with another and the information was lost. The system then corrects the problem. This is not as efficient but is easy to do and cheap to implement. This is what Ethernet uses.

Finally as systems are deployed and interact with each other in a certain physical space they need to divide up the space. This can be done by frequency or cables or physical area or by time or all of the above.

In our discussion SMS are best likened to frequencies (although this is not an exact analogy). The advantage of them is that no two NGOs can ever end up with the same long code as this is handled by the carriers and their agreements. Internationally no two carriers can ever issue the same phone number or long code globally. If all NGOs stuck with long codes or full phone numbers we could avoid the problem Patrick is rightly concerned with.

NGOs and other organizations can problematically and mistakenly issue the same short code within a geographic area and we should all be concerned about this exactly as Patrick is. This problem can happen because short codes are for humans – not for the system itself. If the carriers are using different underlying cell phone technologies they can both issue the same short code and neither will interfere technically with the other one. Unfortunately it could have disastrous consequences for the socialization of the short codes to the local or larger population if they cross either technical or geographic lines. This is a problem largely unique to SMS and the plethora of technologies,carriers, bands (or frequencies) that can be deployed in a large physical area and the fact that short codes are for human convenience.

Right now there are 14 frequency bands just within the GSM voice system (thankfully quad band phones support all the widely used ones) and another 14 for data (furthermore the data “bands” actually cover a huge range of frequencies). This is why it is possible to have within one region, country or city with two “overlapping” short codes on two or more different carriers – the codes will each work only on the carrier that operates on that actual GSM frequency band. The system doesn’t care but it can be confusing to us humans.

Another thing Patrick has raised as a concern is actually “subject matter frequency” overlap (or collisions) and the confusion that can result to us simpleminded humans.

It makes no difference how many SMS codes are used as long as they are long codes OR if private and on short codes. The only time there is a problem is when two groups set up short codes that become public (meaning they are advertised in some way to the general public) as “the right number for X” where X is the same subject matter area.

In order to speed response many countries do NOT follow the US 911 system which uses a single short number for all emergencies. For instance Austria uses no less than 9 “short code” voice numbers each for a separate emergency type. That’s great if you live there and have them all memorized and know that for extreme sports there is a number just for “alpine rescue” to get your friend off some ledge that he crashed into in his para-glider. It speeds vital response and gets the right team dispatched in the least time. It does however require a massive amount of public education.

In the US the government decided to have a “one number fits all” system. This was in response to the fact that previously we had thousands of local numbers for each fire and police department, hospital and ambulance service. Without a local phone book it wasn’t possible to know who to call in an emergency. We designed the 911 system as a way to solve this problem and looped all three major responders into the one system. This was then deployed on a county by county basis across the US. There is no national 911 system. The system scales by dividing itself into small geographic sections.

SMS systems tend to be larger in size because SMS carriers are geographically larger that the old local phone POP (point of presence) that became the basis of the US 911 system. Another major concern for SMS design is the total carrying capacity of the carrier SMS system itself. SMS is NOT designed to be use for “one to many” messages. That was never part of the design and the system can be knocked out if the overall limits of the system are exceeded. At that point the SMS systems themselves collapse under the load and start failing and can cause a cascade failure of the entire carrier network in a region – this means that SMS can knock out voice. It does appear that such a failure occurred in Haiti to one of the local carriers that implemented an SMS emergency broadcast system in conjunction with an NGO so this is a real problem.

Getting back to Patrick’s identified concern – we should be worried when multiple SMS “subject channels” are socialized via the mass media and it confuses the public. In Haiti that didn’t happen because there was only one due largely to the work and efforts of the 4636 Haiti.Ushahidi community.

I believe in the future that is also unlikely to happen because I hope the mass media outlets will simply refuse to say “use any of the following SMS codes for health and these for x and y and z.” I think they won’t do this haphazardly. Doing so (meaning confusing the public) could endanger their (mass media) operating license from the host country.

Furthermore countries and cities are typically aware of this whole discussion and carefully control the distribution of short codes (but this does vary widely from region to region). The country that issues the carrier the license to operate the infrastructure is the ultimate authority for this and reserves the right to yank someone off the air or kick them out of the country for failure to follow the rules. Frequency spectrum must be managed for the greater public good or the classic “crisis of the commons” will result. This is the concern Patrick has brought to light.

One can not and should not assume that the rules, laws and policies we (individuals) are used to operating under in our home country apply elsewhere. The term “sovereign nation” means exactly that – they set their own laws concerning how things operate – including technology and communications systems. For instance WiFi is NOT WiFi everywhere and a WiFI router sold in Japan is illegal to operate in the US.

Some well meaning but largely uneducated NGOs deployed systems in Haiti that badly broke rules, laws, policies, etc and the Government of Haiti (and the US Government on behalf of the Haitian Government) was very polite to them. They stepped all over local businesses and disrupted them. Had this happened in the US the FCC would have issued huge fines to them – fines that likely would drive them out of business – and for good reason. They are exploiting the “public commons” for their own advantage. Whether they meant to or not is irrelevant just as ignorance of the law is no excuse.

In the past most responders to such emergencies were large NGOs with trained communications teams that knew they must coordinate their use of various communications platforms with each other or everyone would suffer. In this past this was easy and obvious because NGOs, governments and businesses made extensive use of UHF and VHF radios for communications. Because these systems were voice based it was obvious when you had a problem and when someone was on your assigned frequency. Furthermore you frequently had the opportunity to yell at them over that same communications system.

In the era of digital communications systems we no longer have the ability to yell at anyone and in fact both the designed legal and official user and the illegal user may be unaware that they are colliding and causing both systems to fail. This is a huge problem because it means that both parties have no way to know even know they are interfering with each other much less how or where to resolve the problem.

In conclusion, I applaud Patrick’s efforts as he has raised an important issue that all NGOs that respond to emergencies (both in the US and abroad) must to be aware of. Education is critical. Please tell your organization that they must contact and coordinate with the official frequency manager, typically the local government’s communications agency or ministry, prior to deploying any communications equipment. Failing to do so is typically illegal and can have grave consequences in emergencies, crises and disasters.