There were a number of mapping-related papers, posters and demo’s at ICTD2009. One paper in particular caught my intention given the topic’s direct relevance to my ongoing consulting work with the UN’s Threat and Risk Mapping Analysis (TRMA) project in the Sudan and the upcoming ecosystem project in Liberia with Ushahidi and Humanity United.

Introduction

Entitled “Folksomaps – Towards Community Intelligent Maps for Developing Regions,” the paper outlines a community-driven approach for creating maps by drawing on “Web 2.0 principles” and “Semantic Web technologies” but without having to rely entirely on a web-based interface. Indeed, Folksomaps “makes use of web and voice applications to provide access to its services.”

I particularly value the authors’ aim to “provide map-based services that represent user’s intuitive way of finding locations and directions in developing regions.” This is an approach that definitely resonates with me. Indeed, it is our responsibility to adapt and customize our community-based mapping tools to meet the needs, habits and symbology of the end user; not the other way around.

I highly recommend this paper (or summary below) to anyone doing work in the crisis mapping field. In fact, I consider it required reading. The paper is co-authored by Arun Kumar, Dipanjan Chakraborty, Himanshu Chauhan, Sheetal Agarwal and Nitendra Rajput of IBM India Research Lab in New Delhi.

Background

Vast rural areas of developing countries do not have detailed maps or mapping tools. Rural populations are generally semi-literate, low-income and non-tech savvy. They are hardly like to have access to neogeography platforms like Google Earth. Moreover, the lack of electricity access and Internet connection also complicates the situation.

We also know that cities, towns and villages in developing countries “typically do not have well structured naming of streets, roads and houses,” which means “key landmarks become very important in specifying locations and directions.”

Drawing on these insights, the authors seek to tap the collective efforts of local communities to populate, maintain and access content for their own benefit—an approach I have described as crowdfeeding.

Surveys of Tech and Non-Tech Users

The study is centered on end-user needs, which is rather refreshing. The authors carried out a series of surveys to be better understand the profiles of end-users, e.g., tech and non-tech users.

The first survey sought to identify answers to the following questions:

- How do people find out points of interest?

- How do much people rely on maps versus people on the streets?

- How do people provide local information to other people?

- Whether people are interested in consuming and feeding information for a community-driven map system?

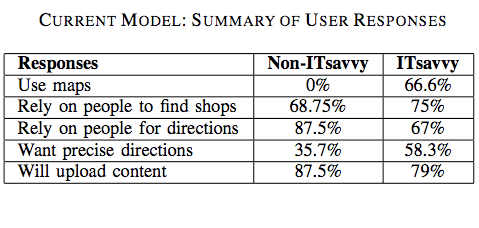

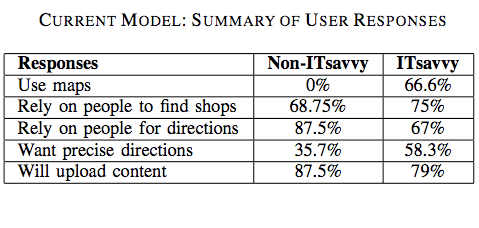

The results are listed in the table below:

Non-tech savvy users did not use maps to find information about locations and only 36% of these users required precise information. In addition, 75% of non-tech respondents preferred the choice of a phone-based interface, which really drives home the need for what I have coined “Mobile Crisis Mapping” or MCM.

Tech-users also rely primarily on others (as opposed to maps) for location related information. The authors associate this result with the lack of signboards in countries like India. “Many a times, the maps do not contain fine-grained information in the first place.”

Most tech-users responded that a phone-based location and direction finding system in addition to a web-based interface. Almost 80% expressed interest in “contributing to the service by uploading content either over the phone or though a web-based portal.”

The second survey sought to identify how tech and non-tech users express directions and local information. For example:

- How do you give directions to people on the road or to friends?

- How do you describe proximity of a landmark to another one?

- How do you describe distance? Kilometers or using time-to-travel?

The results are listed in the table below:

The majority of non-tech savvy participants said they make use of landmarks when giving directions. “They use names of big roads […] and use ‘near to’, ‘adjacent to’, ‘opposite to’ relations with respect to visible and popular landmarks […].” Almost 40% of responders said they use time only to describe the distance between any two locations.

Tech-savvy participants almost always use both time and kilometers as a measure to represent distance. Only 10% or so of participants used kilometers only to represent distance.

The Technology

The following characteristics highlight the design choices that differentiate Folksomaps from established notions of map systems:

- Relies on user generated content rather than data populated by professionals;

- Strives for spatial integrity in the logical sense and does not consider spatial integrity in the physical sense as essential (which is a defining feature of social maps);

- Does not consider visual representation as essential, which is important considering the fact that a large segment of users in developing countries do not have access to Internet (hence my own emphasis on mobile crisis mapping);

- Is non-static and intelligent in the sense that it infers new information from what is entered by the users.

- User input is not verified by the system and it is possible that pieces of incorrect information in the knowledgebase may be present at different points of time. Folksomaps adopts the Wiki model and allows all users to add, edit and remove content freely while keeping maps up-to-date.

Conceptual Design

Folksomaps uses “landmark” as the basic unit in the mapping knowledgebase model while “location” represents more coarse-grained geographical areas such as a village, city or country. The model then seeks to capture a few key logical characteristics of locations such as direction, distance, proximity and reachability and layer.

The latter constitutes the granularity of the geographic area that a location represents. “The notion of direction and distance from a location is interpreted with respect to the layer that the location represents. In other words, direction and distance could be viewed as binary operator over locations of the same level. For instance, ‘is towards left of ’ would be appropriate if the location pair being considered is <Libya, Egypt>,” but not if the pair is <Nairobi, India>.

The knowledgebase makes use of two modules, the Web Ontology Language (OWL) and a graph database, to represent and store the above concepts. The Semantic Web language OWL is used to model the categorical characteristics of a landmark (e.g., direction, proximity, etc), and thence infer new relationships not explicitly specified by users of the system. In other words, OWL provides an ontology of locations.

The graph database is used represent distance (numerical relationships) between landmarks. “The locations are represented by nodes and the edges between two nodes of the graph are labeled with the distance between the corresponding locations.” Given the insights gained from user surveys, precise distances and directions are not integral components of community-based maps.

The two modules are used to generate answers to queries submitted by users.

User Interaction

The authors rightly recognize that the user interface design is critical to the success of community-based mapping projects. To be sure, users of may be illiterate, or semi-illiterate and not very tech-savvy. Furthermore, users will tend to query the map system when they need it most, e.g., “when they are stuck on the road looking for directions […] and would be pressed for time.” This very much holds true for crisis mapping as well.

Users can perform three main tasks with the system: “find place”, “trace path” and “add info.” In addition, some or all users may be granted the right to edit or remove entries from the knowledgebase. The Folksomaps system can also be bootstrapped from existing databases to populate instances of location types. “Two such sources of data in the absence of a full-fledged Geographical Information System (GIS) come from the Telecom Industry and the Postal Department.”

How the users interface with the system to carry out these tasks will depend on how tech-savvy or literate they are and what type of access they have to information and communication technologies.

Folksomaps thus provides three types of interface: web-based, voice-based and SMS-based. Each interface allows the user to query and update the database. The web-based interface was developed using Java Server Pages (JSP) while the voice-based interface uses JSPs and VoiceXML.

I am particularly interested in the voice-based interface. The authors point to previous studies that suggest a voice-based interaction works well with users who are illiterate or semi-illiterate and who cannot afford to have high-end devices but can use ordinary low-end phones.

I will share this with the Ushahidi development team with the hopes that they will consider adding a voice-based interface for the platform later this year. To be sure, could be very interesting to integrate Freedom Fone’s work in this area.

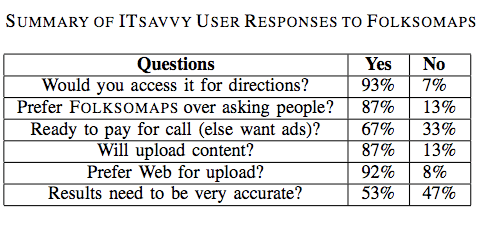

Insights from User Studies

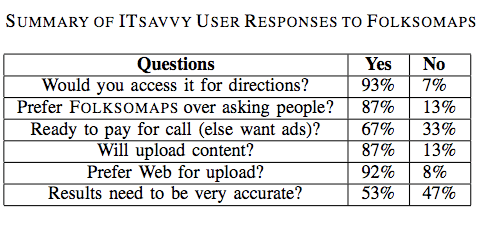

The authors conducted user studies to verify the benefit and acceptability of Folksomaps. Tech-savvy used the web-based interface while non-tech savvy participants used the voice-based interface. The results are shown in the two tables below.

Several important insights surfaced from the results of the user studies. For example, an important insight gained from the non-tech user feedback was “the sense of security that they would get with such a system. […] Even though asking for travel directions from strangers on the street is an option, it exposes the enquirer to criminal elements […].”

Another insight gain was the fact that many non-tech savvy participants were willing to pay for the call even a small premium over normal charges as they saw value to having this information available to them at all times.” That said, the majority of participants “preferred the advertisement model where an advertisement played in the beginning of the call pays for the entire call.”

Interestingly, almost all participants preferred the voice-based interface over SMS even though the former led to a number of speech recognition errors. The reason being that “many people are either not comfortable using SMS or not comfortable using a mobile phone itself.”

There were also interesting insights on the issue of accuracy from the perspective of non-tech savvy participants. Most participants asked for full accuracy and only a handful were tolerant of minor mistakes. “In fact, one of the main reasons for preferring a voice call over asking people for directions was to avoid wrong directions.”

This need for high accuracy is driven by the fact that most people use public transportation, walk or use a bicycle to reach their destination, which means the cost of incorrect information is large compared to someone who owns a car.

This is an important insight since the authors had first assumed that tolerance for incorrect information was higher. They also learned that meta information is as important to non-tech savvy users as the landmarks themselves. For instance, low-income participants were more interested in knowing the modes of available transportation, timetables and bus route numbers than the road route from a source to a destination.

In terms of insights from tech-savvy participants, they did not ask for fine-grained directions all the time. “They were fight with getting high level directions involving major landmarks.” In addition, the need for accuracy was not as strong as for the non-tech savvy respondents and they preferred the content from the queries sent to them via SMS so they could store it for future access, “pointing out that it is easy to forget the directions if you just hear it.”

Some tech-savvy participants also suggested that the directions provided by Folksomaps should “take into consideration the amount of knowledge the subject already has about the area, i.e., it should be personalized based upon user profile. Other participants mentioned that “frequent changes in road plans due to constructions should be captured by such a system—thus making it more usable than just getting directions.”

Conclusion

In sum, the user interface of Folksomaps needs to be “rich and adaptive to the information needs of the user […].” To be sure, given user preference towards “voice-based interface over SMS, designing an efficient user-friendly voice-based user interface […].” In addition, “dynamic and real-time information augmented with traditional services like finding directions and locations would certainly add value to Folksomaps.” Furthermore, the authors recognize that Folksomaps can “certainly benefit from user interface designs,” and “multi-model front ends.”

Finally, the user surveys suggest “the community is very receptive towards the concept of a community-driven map,” so it is important that the TRMA project in the Sudan and the ecosystem Liberia project build on the insights and lessons learned provided in this study.

Patrick Philippe Meier