Published by ALNAP, the 2012 State of the Humanitarian System report is an important evaluation of the humanitarian community’s efforts over the past two years. “I commend this report to all those responsible for planning and delivering life saving aid around the world,” writes UN Under-Secretary General Valerie Amos in the Preface. “If we are going to improve international humanitarian response we all need to pay attention to the areas of action highlighted in the report.” Below are some of the highlighted areas from the 100+ page evaluation that are ripe for innovative interventions.

Accessing Those in Need

Operational access to populations in need has not improved. Access problems continue and are primarily political or security-related rather than logistical. Indeed, “UN security restrictions often place sever limits on the range of UN-led assessments,” which means that “coverage often can be compromised.” This means that “access constraints in some contexts continue to inhibit an accurate assessment of need. Up to 60% of South Sudan is inaccessible for parts of the year. As a result, critical data, including mortality and morbidity, remain unavailable. Data on nutrition, for example, exist in only 25 of 79 countries where humanitarian partners have conducted surveys.”

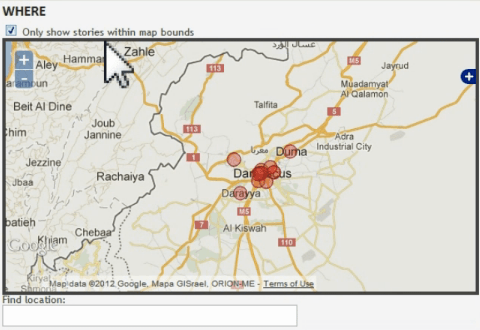

Could satellite and/or areal imagery be used to measure indirect proxies? This would certainly be rather imperfect but perhaps better than nothing? Could crowdseeding be used?

Information and Communication Technologies

“The use of mobile devices and networks is becoming increasingly important, both to deliver cash and for communication with aid recipients.” Some humanitarian organizations are also “experimenting with different types of communication tools, for different uses and in different contexts. Examples include: offering emergency information, collecting information for needs assessments or for monitoring and evaluation, surveying individuals, or obtaining information on remote populations from an appointed individual at the community level.”

“Across a variety of interventions, mobile phone technology is seen as having great potential to increase efficiency. For example, […] the governments of Japan and Thailand used SMS and Twitter to spread messages about the disaster response.” Naturally, in some contexts, “traditional means like radios and call centers are most appropriate.”

In any case, “thanks to new technologies and initiatives to advance commu-nications with affected populations, the voices of aid recipients began, in a small way, to be heard.” Obviously, heard and understood are not the same thing–not to mention heard, understood and responded to. Moreover, as disaster affected communities become increasingly “digital” thanks to the spread of mobile phones, the number of voices will increase significantly. The humanitarian system is largely (if not completely) unprepared to handle this increase in volume (Big Data).

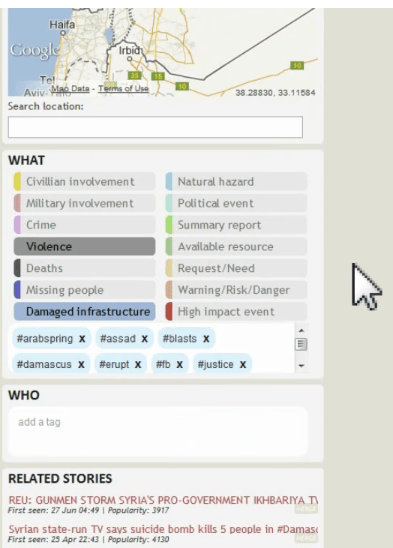

Consulting Local Recipients

Humanitarian organizations have “failed to consult with recipients […] or to use their input in programming.” Indeed, disaster-affected communities are “rarely given opportunities to assess the impact of interventions and to comment on performance.” In fact, “they are rarely treated as end-users of the service.” Aid recipients also report that “the aid they received did not address their ‘most important needs at the time.'” While some field-level accountability mechanisms do exist, they were typically duplicative and very project oriented. To this end, “it might be more efficient and effective to have more coordination between agencies regarding accountability approaches.”

While the ALNAP report suggests that these shortcomings could “be addressed in the near future by technical advances in methods of needs assessment,” the challenge here is not simply a technical one. Still, there are important efforts underway to address these issues.

Improving Needs Assessments

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s (IASC) Needs Assessment Task Force (NAFT) and the International NGO-led Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS) are two such exempts of progress. OCHA serves as the secretariat for the NAFT through its Assessment and Classification of Emergencies (ACE) Team. ACAPS, which is a consortium of three international NGOs (X, Y and Z) and a member of NATF, aims to “strengthen the capacity of the humanitarian sector in multi-sectoral needs assessment.” ACAPS is considered to have “brought sound technical processes and practical guidelines to common needs assessment.” Note that both ACAPS and ACE have recently reached out to the Digital Humanitarian Network (DHNetwork) to partner on needs-assessment projects in South Sudan and the DRC.

Another promising project is the Humanitarian Emergency Settings Perceived Needs Scale (HESPER). This join initiative between WHO and King’s College London is designed to rapidly assess the “perceived needs of affected populations and allow their views to be taken into consideration. The project specifically aims to fill the gap between population-based ‘objective’ indicators […] and/or qualitative data based on convenience samples such as focus groups or key informant interviews.” On this note, some NGOs argue that “overall assessment methodologies should focus far more at the community (not individual) level, including an assessment of local capacities […],” since “far too often international aid actors assume there is no local capacity.”

Early Warning and Response

An evaluation of the response in the Horn of Africa found “significant disconnects between early warning systems and response, and between technical assessments and decision-makers.” According to ALNAP, “most commentators agree that the early warning worked, but there was a failure to act on it.” This disconnect is a concern I voiced back in 2009 when UN Global Pulse was first launched. To be sure, real-time information does not turn an organization into a real-time organization. Not surprisingly, most of the aid recipients surveyed for the ALNAP report felt that “the foremost way in which humanitarian organizations could improve would be to: ‘be faster to start delivering aid.'” Interestingly, “this stands in contrast to the survey responses of international aid practitioners who gave fairly high marks to themselves for timeliness […].”

Rapid and Skilled Humanitarians

While the humanitarian system’s surge capacity for the deployment of humanitarian personnel has improved, “findings also suggest that the adequate scale-up of appropriately skilled […] staff is still perceived as problematic for both operations and coordination.” Other evaluations “consistently show that staff in NGOs, UN agencies and clusters were perceived to be ill prepared in terms of basic language and context training in a significant number of contexts.” In addition, failures in knowledge and understanding of humanitarian principles were also raised. Furthermore, evaluations of mega-disasters “predictably note influxes or relatively new staff with limited experience.” Several evaluations noted that the lack of “contextual knowledge caused a net decrease in impact.” This lend one senior manager noted:

“If you don’t understand the political, ethnic, tribal contexts it is difficult to be effective… If I had my way I’d first recruit 20 anthropologists and political scientists to help us work out what’s going on in these settings.”

Monitoring and Evaluation

ALNAP found that monitoring and evaluation continues to be a significant shortcoming in the humanitarian system. “Evaluations have made mixed progress, but affected states are still notably absent from evaluating their own response or participating in joint evaluations with counterparts.” Moreover, while there have been important efforts by CDAC and others to “improve accountability to, and communication with, aid recipients,” there is “less evidence to suggest that this new resource of ground-level information is being used strategically to improve humanitarian interventions.” To this end, “relatively few evaluations focus on the views of aid recipients […].” In one case, “although a system was in place with results-based indicators, there was neither the time nor resources to analyze or use the data.”

The most common reasons cited for failing to meet community expectations include the “inability to meet the full spectrum of need, weak understanding of local context, inability to understand the changing nature of need, inadequate information-gathering techniques or an inflexible response approach.” In addition, preconceived notions of vulnerability have “led to inappropriate interventions.” A major study carried out by Tufts University and cited in the ALNAP report concludes that “humanitarian assistance remains driven by ‘anecdote rather than evidence’ […].” One important exception to this is the Danish Refugee Council’s work in Somalia.

Leadership, Risk and Principles

ALNAP identifies an “alarming evidence of a growing tendency towards risk aversion” and a “stifling culture of compliance.” In addition, adherence to humanitarian principles were found to have weakened as “many humanitarian organizations have willingly compromised a principled approach in their own conduct through close alignment with political and military activities and actors.” Moreover, “responses in highly politicized contexts are viewed as particularly problematic for the retention of humanitarian principles.” Humanitarian professionals who were interviewed by ALNAP for this report “highlighted multiple occasions when agencies failed to maintain an impartial response when under pressure from strong states, such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka.”