This blog entry was inspired by Ory’s recent blog post on “Covering the DRC – challenges for Ushahidi.” The thoughts that follow were originally intended for the comments section of Ushahidi’s blog but they surreptitiously morphed into a more in depth reflection. First, however, many thanks to Ory for taking the time to share the team’s experience in the DRC over the past few weeks.

Much of what Ory writes resonates with my own experience in conflict early warning/response. While several factors contribute to the challenge of Ushahidi’s deployment, I think one in particular regrettably remains a constant in my own experience: the link to early response, or rather the lack thereof. The main point I want to make is this: if Ushahidi addresses the warning-response gap, then Ushahidi-DRC is likely to get far more traction on the ground than it currently is.

To explain, if Ushahidi is going to provide a platform that enables the crowdsourcing of crisis information, then it must also facilitate the crowdsourcing of response. Why? For otherwise the tool is of little added value to the individuals who constitute said crowd, ie, the Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP) in conflict zones. If individuals at the BoP don’t personally benefit from Ushahidi, then they should not be spending time/resources on communicating alerts. As one of my dissertation committee members, Peter Walker wrote in 1991 vis-a-vis famine early warning/response systems in Africa:

It must be clearly understood that the informants are the most important part of the information system. It is their information […] upon which the rest of the system is based […]. The informant must be made to feel, quite rightly, that he or she is an important part of the system, not just a minion at the base, for ever giving and never receiving.

In 1988 (that’s write ’88), Kumar Rupesinghe published a piece on disaster early warning systems in which he writes that civil society has

… a vital role to play in the development of a global, decentralized early warning system. They now need the capacity to build information systems and to provide the basis for rapid information exchange. In general [civil society] will have to confront the monopolization of information with a demand for the democratic access to information technology.

Information on local concerns must be available to the local structures in society. The right to be informed and the right to information have to find entry into international discussions.

Ushahidi’s crowdsourcing approach has the potential to reverse the monopolization of information and thereby create a demand for access to conflict information. Indeed, Ushahidi is starting to influence the international discourse on early warning (forthcoming reports by the EC and OECD). However, it is the mobile crowdsourcing of response that will create value and thereby demand by the BoP for Ushahidi.

Put it this way, Twitter would be far less useful if it were limited to one (and only one) global website on which all tweets were displayed. What makes Twitter valuable is the ability to select specific feeds, and to have those feeds pushed to us effortlessly, using Twhirl or similar programs, and displayed (in less than 141 characters) on our computer screens in real time. At the moment, Ushahidi does the equivalent of the former, but not the latter.

Yet the latter is precisely where the added value to the individual lies. An NGO may be perfectly content with Ushahidi’s current set up, but NGOs do not constitute the BoP; they are not the “fundamental unit” of crowdsourcing—individuals are. (Just imagine if Wikipedia entries could only be written/edited by NGOs).

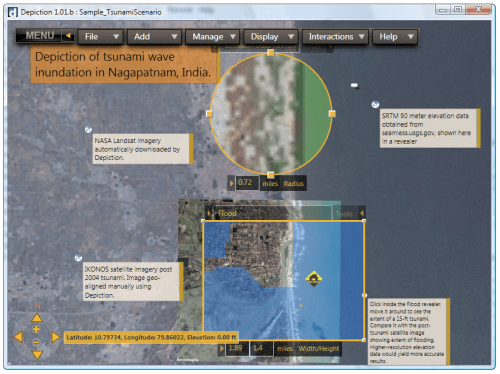

This mismatch in fundamental units is particularly prevalent in the conflict early warning/response field. NGOs do not have the same incentive structures as individuals. If individuals in at-risk communities were to receive customized alerts on incidents in/near their own town (if they themselves send alerts to Ushahidi), then that response presents a far more direct and immediate return on investment. Receiving geo-specific alerts in quasi real-time improves situational awareness and enables an individual to take a more informed decision about how to respond to the alerts. That is added value. The BoP would have an incentive, empowerment, to crowdsource crisis information.

Here’s a scenario: if an individual texts in an alert for the first time, Ushahidi should: (1) contact that person as soon as possible to thank them for their alert and, (2) ask them what SMS alerts they would like to receive and for what town(s). I guarantee you this person will spread the word through their own social network and encourage others to send in alerts so that they too may receive alerts. (Incidentally, Erik, this is the strategy I would recommend in places like Jos, Nigeria).

In summary, while the Ushahidi team faces a multitude of other challenges in the DRC deployment, I believe that addressing the early response dimension will render the other challenges more manageable. While the vast majority of conflict early warning systems are wired vertically (designed by outsiders for outsiders), the genius of Ushahidi is the paradigm shift to horizontally wired, local early warning/response, aka crowdsourcing.

In a way, it’s very simple: If Ushahidi can create value for the BoP, the client base will necessarily expand (substantially). To this end, Ushahidi should not be pitched as an early warning system, but rather as an early response service. This is one of the reasons why I am trying hard to encourage the operationalization of mobile crisis mapping.