Can microblogged data fit the information needs of humanitarian organizations? This is the question asked by a group of academics at Pennsylvania State University’s College of Information Sciences and Technology. Their study (PDF) is an important contribution to the discourse on humanitarian technology and crisis information. The applied research provides key insights based on a series of interviews with humanitarian professionals. While I largely agree with the majority of the arguments presented in this study, I do have questions regarding the framing of the problem and some of the assertions made.

The authors note that “despite the evidence of strong value to those experiencing the disaster and those seeking information concerning the disaster, there has been very little uptake of message data by large-scale, international humanitarian relief organizations.” This is because real-time message data is “deemed as unverifiable and untrustworthy, and it has not been incorporated into established mechanisms for organizational decision-making.” To this end, “committing to the mobilization of valuable and time sensitive relief supplies and personnel, based on what may turn out be illegitimate claims, has been perceived to be too great a risk.” Thus far, the authors argue, “no mechanisms have been fashioned for harvesting microblogged data from the public in a manner, which facilitates organizational decisions.”

I don’t think this latter assertion is entirely true if one looks at the use of Twitter by the private sector. Take for example the services offered by Crimson Hexagon, which I blogged about 3 years ago. This successful start-up launched by Gary King out of Harvard University provides companies with real-time sentiment analysis of brand perceptions in the Twittersphere precisely to help inform their decision making. Another example is Storyful, which harvests data from authenticated Twitter users to provide highly curated, real-time information via microblogging. Given that the humanitarian community lags behind in the use and adoption of new technologies, it behooves us to look at those sectors that are ahead of the curve to better understand the opportunities that do exist.

Since the study principally focused on Twitter, I’m surprised that the authors did not reference the empirical study that came out last year on the behavior of Twitter users after the 8.8 magnitude earthquake in Chile. The study shows that about 95% of tweets related to confirmed reports validated that information. In contrast only 0.03% of tweets denied the validity of these true cases. Interestingly, the results also show that “the number of tweets that deny information becomes much larger when the information corresponds to a false rumor.” In fact, about 50% of tweets will deny the validity of false reports. This means it may very well be posible to detect rumors by using aggregate analysis on tweets.

On framing, I believe the focus on microblogging and Twitter in particular misses the bigger picture which ultimately is about the methodology of crowdsourcing rather than the technology. To be sure, the study by Penn State could just as well have been titled “Seeking the Trustworthy SMS.” I think this important research on microblogging would be stronger if this distinction were made and the resulting analysis tied more closely to the ongoing debate on crowdsourcing crisis information that began during the response to Haiti’s earthquake in 2010.

Also, as was noted during the Red Cross Summit in 2010, more than two-thirds of respondents to a survey noted that they would expect a response within an hour if they posted a need for help on a social media platform (and not just Twitter) during a crisis. So whether humanitarian organizations like it or not, crowdsourced social media information cannot be ignored.

The authors carried out a series of insightful interviews with about a dozen international humanitarian organizations to try and better understand the hesitation around the use of Twitter for humanitarian response. As noted earlier, however, it is not Twitter per se that is a concern but the underlying methodology of crowdsourcing.

As expected, interviewees noted that they prioritize the veracity of information over the speed of communication. “I don’t think speed is necessarily the number one tool that an emergency operator needs to use.” Another interviewee opined that “It might be hard to trust the data. I mean, I don’t think you can make major decisions based on a couple of tweets, on one or two tweets.” What’s interesting about this latter comment is that it implies that only one channel of information, Twitter, is to be used in decision-making, which is a false argument and one that nobody I know has ever made.

Either way, the trade-off between speed and accuracy is a well known one. As mentioned in this blog post from 2009, information is perishable and accuracy is often a luxury in the first few hours and days following a major disaster. As the authors for the study rightly note, “uncertainty is ‘always expected, if sometimes crippling’ (Benini, 1997) for NGOs involved in humanitarian relief.” Ultimately, the question posed by the authors of the Penn study can be boiled down to this: is some information better than no information if it cannot be immediately verified? In my opinion, yes. If you have some information, then at least you can investigate it’s veracity which may lead to action. I also believe that from this philosophical point of view, the answer would still be yes.

Based on the interviews, the authors found that organizations engaged in immediate emergency response were less likely to make use of Twitter (or crowdsourced information) as a channel for information. As one interviewee put it, “Lives are on the line. Every moment counts. We have it down to a science. We know what information we need and we get in and get it…” In contrast, those organizations engaged in subsequent phases of disaster response were thought more likely to make use of crowdsourced data.

I’m not entirely convinced by this: “We know what information we need and we get in and get it…”. Yes, humanitarian organizations typically know but whether they get it, and in time, is certainly not a given. Just look at the humanitarian responses to Haiti and Libya, for example. Organizations may very well be “unwilling to trade data assurance, veracity and authenticity for speed,” but sometimes this mindset will mean having absolutely no information. This is why OCHA asked the Standby Volunteer Taskforce to provide them with a live crowdsourced social media may of Libya. In Haiti, while the UN is not thought to have used crowdsourced SMS data from Mission 4636, other responders like the Marine Corps did.

Still, according to one interviewee, “fast is good, but bad information fast can kill people. It’s got to be good, and maybe fast too.” This assumes that no information doesn’t kill people. Also good information that is late, can also kill people. As one of the interviewees admitted when using traditional methods, “it can be quite slow before all that [information] trickles through all the layers to get to us.” The authors of the study also noted that, “Many [interviewees] were frustrated with how slow the traditional methods of gathering post-disaster data had remained despite the growing ubiquity of smart phones and high quality connectivity and power worldwide.”

On a side note, I found the following comment during the interviews especially revealing: “When we do needs assessments, we drive around and we look with our eyes and we talk to people and we assess what’s on the ground and that’s how we make our evaluations.” One of the common criticisms leveled against the use of crowdsourced information is that it isn’t representative. But then again, driving around, checking things out and chatting with people is hardly going to yield a representative sample either.

One of the main findings from this research has to do with a problem in attitude on the part of humanitarian organizations. “Each of the interviewees stated that their organization did not have the organizational will to try out new technolo-gies. Most expressed this as a lack of resources, support, leadership and interest to adopt new technologies.” As one interview noted, “We tried to get the president and CEO both to use Twitter. We failed abysmally, so they’re not– they almost never use it.” Interestingly, “most of the respondents admitted that many of their technological changes were motivated by the demands of their donors. At this point in time their donors have not demanded that these organizations make use of microblogged data. The subjects believed they would need to wait until this occurred for real change to begin.”

For me the lack of will has less to do with available resources and limited capacity and far more to do with a generational gap. When today’s young professionals in the humanitarian space work their way up to more executive positions, we’ll see a significant change in attitude within these organizations. I’m thinking in particular of the many dozens of core volunteers who played a pivotal role in the crisis mapping operations in Haiti, Chile, Pakistan, Russia and most recently Libya. And when attitude changes, resources can be reallocated and new priorities can be rationalized.

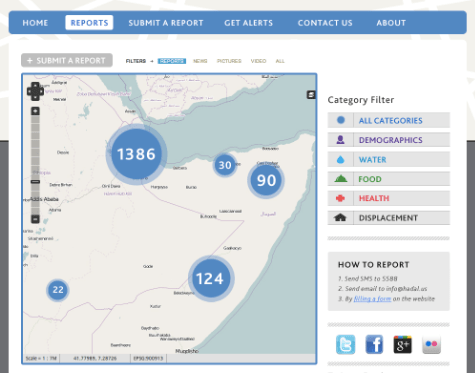

What’s interesting about these interviews is that despite all the concerns and criticisms of crowdsourced Twitter data, all interviewees still see microblogged data as a “vast trove of potentially useful information concerning a disaster zone.” One of the professionals interviewed said, “Yes! Yes! Because that would – again, it would tell us what resources are already in the ground, what resources are still needed, who has the right staff, what we could provide. I mean, it would just – it would give you so much more real-time data, so that as we’re putting our plans together we can react based on what is already known as opposed to getting there and discovering, oh, they don’t really need medical supplies. What they really need is construction supplies or whatever.”

Another professional stated that, “Twitter data could potentially be used the same way… for crisis mapping. When an emergency happens there are so many things going on in the ground, and an emergency response is simply prioritization, taking care of the most important things first and knowing what those are. The difficult thing is that things change so quickly. So being able to gather information quickly…. <with Twitter> There’s enormous power.”

The authors propose three possible future directions. The first is bounded microblogging, which I have long referred to as “bounded crowdsourcing.” It doesn’t make sense to focus on the technology instead of the methodology because at the heart of the issue are the methods for information collection. In “bounded crowdsourcing,” membership is “controlled to only those vetted by a particular organization or community.” This is the approach taken by Storyful, for example. One interviewee acknowledge that “Twitter might be useful right after a disaster, but only if the person doing the Tweeting was from <NGO name removed>, you know, our own people. I guess if our own people were sending us back Tweets about the situation it could help.”

Bounded crowdsourcing overcomes the challenge of authentication and verification but obviously with a tradeoff in the volume of data collected “if an additional means were not created to enable new members through an automatic authentication system, to the bounded microblogging community.” However, the authors feel that bounded crowdsourcing environments “undermine the value of the system” since “the power of the medium lies in the fact that people, out of their own volition, make localized observations and that organizations could harness that multitude of data. The bounded environment argument neutralizes that, so in effect, at that point, when you have a group of people vetted to join a trusted circle, the data does not scale, because that pool by necessity would be small.”

That said, I believe the authors are spot on when they write that “Bounded environments might be a way of introducing Twitter into the humanitarian centric organizational discourse, as a starting point, because these organizations, as seen from the evidence presented above, are not likely to initially embrace the medium. Bounded environments could hence demonstrate the potential for Twitter to move beyond the PR and Communications departments.”

The second possible future direction is to treat crowdsourced data is ambient, “contextual information rather than instrumental information, (i.e., factual in nature).” This grassroots information could be considered as an “add-on to traditional, trusted institutional lines of information gathering.” As one interviewee noted, “Usually information exists. The question is the context doesn’t exist…. that’s really what I see as the biggest value [of crowdsourced information] and why would you use that in the future is creating the context…”.

The authors rightly suggest that “that adding contextual information through microblogged data may alleviate some of the uncertainty during the time of disaster. Since the microblogged data would not be the single data source upon which decisions would be made, the standards for authentication and security could be less stringent. This solution would offer the organization rich contextual data, while reducing the need for absolute data authentication, reducing the need for the organization to structurally change, and reducing the need for significant resources.” This is exactly how I consider and treat crowdsourced data.

The third and final forward-looking solution is computational. The authors “believe better computational models will eventually deduce informational snippets with acceptable levels of trust.” They refer to Ushahidi’s SwiftRiver project as an example.

In sum, this study is an important contribution to the discourse. The challenges around using crowdsourced crisis information are well known. If I come across as optimistic, it is for two reasons. First, I do think a lot can be done to address the challenges. Second, I do believe that attitudes in the humanitarian sector will continue to change.