Revised! I have edited this article several dozen times since posting the initial draft. I have also made a number of substantial changes to the flow of the article after discovering new connections, synergies and insights. In addition, I have greatly benefited from reader feedback as well as the very rich conversa-tions that took place during the PopTech & Rockefeller workshop—a warm thank you to all participants for their important questions and feedback!

Introduction

I’ve been invited by PopTech and the Rockefeller Foundation to give the opening remarks at an upcoming event on interdisciplinary dimensions of resilience, which is being hosted at Georgetown University. This event is connected to their new program focus on “Creating Resilience Through Big Data.” I’m absolutely de-lighted to be involved and am very much looking forward to the conversations. The purpose of this blog post is to summarize the presentation I intend to give and to solicit feedback from readers. So please feel free to use the comments section below to share your thoughts. My focus is primarily on disaster resilience. Why? Because understanding how to bolster resilience to extreme events will provide insights on how to also manage less extreme events, while the converse may not be true.

terminology

One of the guiding questions for the meeting is this: “How do you understand resilience conceptually at present?” First, discourse matters. The term resilience is important because it focuses not on us, the development and disaster response community, but rather on local at-risk communities. While “vulnerability” and “fragility” were used in past discourse, these terms focus on the negative and seem to invoke the need for external protection, overlooking the fact that many local coping mechanisms do exist. From the perspective of this top-down approach, international organizations are the rescuers and aid does not arrive until these institutions mobilize.

In contrast, the term resilience suggests radical self-sufficiency, and self-sufficiency implies a degree of autonomy; self-dependence rather than depen-dence on an external entity that may or may not arrive, that may or may not be effective, and that may or may not stay the course. The term “antifragile” just recently introduced by Nassim Taleb also appeals to me. Antifragile sys-tems thrive on disruption. But lets stick with the term resilience as anti-fragility will be the subject of a future blog post, i.e., I first need to finish reading Nassim’s book! I personally subscribe to the following definition of resilience: the capacity for self-organization; and shall expand on this shortly.

(See the Epilogue at the end of this blog post on political versus technical defini-tions of resilience and the role of the so-called “expert”. And keep in mind that poverty, cancer, terrorism etc., are also resilient systems. Hint: we have much to learn from pernicious resilience and the organizational & collective action models that render those systems so resilient. In their book on resilience, Andrew Zolli and Ann Marie Healy note the strong similarities between Al-Qaeda & tuber-culosis, one of which are the two systems’ ability to regulate their metabolism).

Hazards vs Disasters

In the meantime, I first began to study the notion of resilience from the context of complex systems and in particular the field of ecology, which defines resilience as “the capacity of an ecosystem to respond to a perturbation or disturbance by resisting damage and recovering quickly.” Now lets unpack this notion of perturbation. There is a subtle but fundamental difference between disasters (processes) and hazards (events); a distinction that Jean-Jacques Rousseau first articulated in 1755 when Portugal was shaken by an earthquake. In a letter to Voltaire one year later, Rousseau notes that, “nature had not built [process] the houses which collapsed and suggested that Lisbon’s high population density [process] contributed to the toll” (1). In other words, natural events are hazards and exogenous while disas-ters are the result of endogenous social processes. As Rousseau added in his note to Voltaire, “an earthquake occurring in wilderness would not be important to society” (2). That is, a hazard need not turn to disaster since the latter is strictly a product or calculus of social processes (structural violence).

And so, while disasters were traditionally perceived as “sudden and short lived events, there is now a tendency to look upon disasters in African countries in particular, as continuous processes of gradual deterioration and growing vulnerability,” which has important “implications on the way the response to disasters ought to be made” (3). (Strictly speaking, the technical difference between events and processes is one of scale, both temporal and spatial, but that need not distract us here). This shift towards disasters as processes is particularly profound for the creation of resilience, not least through Big Data. To under-stand why requires a basic introduction to complex systems.

complex systems

All complex systems tend to veer towards critical change. This is explained by the process of Self-Organized Criticality (SEO). Over time, non-equilibrium systems with extended degrees of freedom and a high level of nonlinearity become in-creasingly vulnerable to collapse. Social, economic and political systems certainly qualify as complex systems. As my “alma mater” the Santa Fe Institute (SFI) notes, “The archetype of a self-organized critical system is a sand pile. Sand is slowly dropped onto a surface, forming a pile. As the pile grows, avalanches occur which carry sand from the top to the bottom of the pile” (4). That is, the sand pile becomes increasingly unstable over time.

Consider an hourglass or sand clock as an illustration of self-organized criticality. Grains of sand sifting through the narrowest point of the hourglass represent individual events or natural hazards. Over time a sand pile starts to form. How this process unfolds depends on how society chooses to manage risk. A laisser-faire attitude will result in a steeper pile. And grain of sand falling on an in-creasingly steeper pile will eventually trigger an avalanche. Disaster ensues.

Why does the avalanche occur? One might ascribe the cause of the avalanche to that one grain of sand, i.e., a single event. On the other hand, a complex systems approach to resilience would associate the avalanche with the pile’s increasing slope, a historical process which renders the structure increasingly vulnerable to falling grains. From this perspective, “all disasters are slow onset when realisti-cally and locally related to conditions of susceptibility”. A hazard event might be rapid-onset, but the disaster, requiring much more than a hazard, is a long-term process, not a one-off event. The resilience of a given system is therefore not simply dependent on the outcome of future events. Resilience is the complex product of past social, political, economic and even cultural processes.

dealing with avalanches

Scholars like Thomas Homer-Dixon argue that we are becoming increasingly prone to domino effects or cascading changes across systems, thus increasing the likelihood of total synchronous failure. “A long view of human history reveals not regular change but spasmodic, catastrophic disruptions followed by long periods of reinvention and development.” We must therefore “reduce as much as we can the force of the underlying tectonic stresses in order to lower the risk of synchro-nous failure—that is, of catastrophic collapse that cascades across boundaries between technological, social and ecological systems” (5).

Unlike the clock’s lifeless grains of sand, human beings can adapt and maximize their resilience to exogenous shocks through disaster preparedness, mitigation and adaptation—which all require political will. As a colleague of mine recently noted, “I wish it were widely spread amongst society how important being a grain of sand can be.” Individuals can “flatten” the structure of the sand pile into a less hierarchical but more resilience system, thereby distributing and diffusing the risk and size of an avalanche. Call it distributed adaptation.

operationalizing resilience

As already, the field of ecology defines resilience as “the capacity of an ecosystem to respond to a perturbation or disturbance by resisting damage and recovering quickly.” Using this understanding of resilience, there are at least 2 ways create more resilient “social ecosystems”:

- Resist damage by absorbing and dampening the perturbation.

- Recover quickly by bouncing back or rather forward.

Resisting Damage

So how does a society resist damage from a disaster? As hinted earlier, there is no such thing as a “natural” disaster. There are natural hazards and there are social systems. If social systems are not sufficiently resilient to absorb the impact of a natural hazard such as an earthquake, then disaster unfolds. In other words, hazards are exogenous while disasters are the result of endogenous political, economic, social and cultural processes. Indeed, “it is generally accepted among environmental geographers that there is no such thing as a natural disaster. In every phase and aspect of a disaster—causes, vulnerability, preparedness, results and response, and reconstruction—the contours of disaster and the difference between who lives and dies is to a greater or lesser extent a social calculus” (6).

So how do we apply this understanding of disasters and build more resilient communities? Focusing on people-centered early warning systems is one way to do this. In 2006, the UN’s International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) recognized that top-down early warning systems for disaster response were increasingly ineffective. They thus called for a more bottom-up approach in the form of people-centered early warning systems. The UN ISDR’s Global Survey of Early Warning Systems (PDF), defines the purpose of people-centered early warning systems as follows:

“… to empower individuals and communities threatened by hazards to act in sufficient time and in an appropriate manner so as to reduce the possibility of personal injury, loss of life, damage to property and the environment, and loss of livelihoods.”

Information plays a central role here. Acting in sufficient time requires having timely information about (1) the hazard/s, (2) our resilience and (3) how to respond. This is where information and communication technologies (ICTs), social media and Big Data play an important role. Take the latter, for example. One reason for the considerable interest in Big Data is prediction and anomaly detection. Weather and climatic sensors provide meteorologists with the copious amounts of data necessary for the timely prediction of weather patterns and early detection of atmospheric hazards. In other words, Big Data Analytics can be used to anticipate the falling grains of sand.

Now, predictions are often not correct. But the analysis of Big Data can also help us characterize the sand pile itself, i.e., our resilience, along with the associated trends towards self-organized criticality. Recall that complex systems tend towards instability over time (think of the hourglass above). Thanks to ICTs, social media and Big Data, we now have the opportunity to better characterize in real-time the social, economic and political processes driving our sand pile. Now, this doesn’t mean that we have a perfect picture of the road to collapse; simply that our picture is clearer than ever before in human history. In other words, we can better measure our own resilience. Think of it as the Quantified Self move-ment applied to an entirely different scale, that of societies and cities. The point is that Big Data can provide us with more real-time feedback loops than ever before. And as scholars of complex systems know, feedback loops are critical for adaptation and change. Thanks to social media, these loops also include peer-to-peer feedback loops.

An example of monitoring resilience in real-time (and potentially anticipating future changes in resilience) is the UN Global Pulse’s project on food security in Indonesia. They partnered with Crimson Hexagon to forecast food prices in Indonesia by analyzing tweets referring to the price of rice. They found an inter-esting relationship between said tweets and government statistics on food price inflation. Some have described the rise of social media as a new nervous system for the planet, capturing the pulse of our social systems. My colleagues and I at QCRI are therefore in the process of appling this approach to the study of the Arabic Twittersphere. Incidentally, this is yet another critical reason why Open Data is so important (check out the work of OpenDRI, Open Data for Resilience Initiative. See also this post on Demo-cratizing ICT for Development with DIY Innovation and Open Data). More on open data and data philanthropy in the conclusion.

Finally, new technologies can also provide guidance on how to respond. Think of Foursquare but applied to disaster response. Instead of “Break Glass in Case of Emergency,” how about “Check-In in Case of Emergency”? Numerous smart-phone apps such as Waze already provide this kind of at-a-glance, real-time situational awareness. It is only a matter of time until humanitarian organiza-tions develop disaster response apps that will enable disaster-affected commu-nities to check-in for real time guidance on what to do given their current location and level of resilience. Several disaster preparedness apps already exist. Social computing and Big Data Analytics can power these apps in real-time.

Quick Recovery

As already noted, there are at least two ways create more resilient “social eco-systems”. We just discussed the first: resisting damage by absorbing and dam-pening the perturbation. The second way to grow more resilient societies is by enabling them to rapidly recover following a disaster.

As Manyena writes, “increasing attention is now paid to the capacity of disaster-affected communities to ‘bounce back’ or to recover with little or no external assistance following a disaster.” So what factors accelerate recovery in eco-systems in general? In ecological terms, how quickly the damaged part of an ecosystem can repair itself depends on how many feedback loops it has to the non- (or less-) damaged parts of the ecosystem(s). These feedback loops are what enable adaptation and recovery. In social ecosystems, these feedback loops can be comprised of information in addition to the transfer of tangible resources. As some scholars have argued, a disaster is first of all “a crisis in communicating within a community—that is, a difficulty for someone to get informed and to inform other people” (7).

Improving ways for local communities to communicate internally and externally is thus an important part of building more resilient societies. Indeed, as Homer-Dixon notes, “the part of the system that has been damaged recovers by drawing resources and information from undamaged parts.” Identifying needs following a disaster and matching them to available resources is an important part of the process. Indeed, accelerating the rate of (1) identification; (2) matching and, (3) allocation, are important ways to speed up overall recovery.

This explains why ICTs, social media and Big Data are central to growing more resilient societies. They can accelerate impact evaluations and needs assessments at the local level. Population displacement following disasters poses a serious public health risk. So rapidly identifying these risks can help affected populations recover more quickly. Take the work carried out by my colleagues at Flowminder, for example. They empirically demonstrated that mobile phone data (Big Data!) can be used to predict population displacement after major disasters. Take also this study which analyzed call dynamics to demonstrate that telecommunications data could be used to rapidly assess the impact of earthquakes. A related study showed similar results when analyzing SMS’s and building damage Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

Resilience as Self-Organization and Emergence

Connection technologies such as mobile phones allow individual “grains of sand” in our societal “sand pile” to make necessary connections and decisions to self-organize and rapidly recover from disasters. With appropriate incentives, pre-paredness measures and policies, these local decisions can render a complex system more resilient. At the core here is behavior change and thus the importance of understanding behavior change models. Recall also Thomas Schelling’s observation that micro-motives can lead to macro-behavior. To be sure, as Thomas Homer-Dixon rightly notes, “Resilience is an emergent property of a system—it’s not a result of any one of the system’s parts but of the synergy between all of its parts. So as a rough and ready rule, boosting the ability of each part to take care of itself in a crisis boosts overall resilience.” (For complexity science readers, the notions of transforma-tion through phase transitions is relevant to this discussion).

In other words, “Resilience is the capacity of the affected community to self-organize, learn from and vigorously recover from adverse situations stronger than it was before” (8). This link between resilience and capacity for self-organization is very important, which explains why a recent and major evaluation of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake disaster response promotes the “attainment of self-sufficiency, rather than the ongoing dependency on standard humanitarian assistance.” Indeed, “focus groups indicated that solutions to help people help themselves were desired.”

The fact of the matter is that we are not all affected in the same way during a disaster. (Recall the distinction between hazards and disasters discussed earlier). Those of use who are less affected almost always want to help those in need. Herein lies the critical role of peer-to-peer feedback loops. To be sure, the speed at which the damaged part of an ecosystem can repair itself depends on how many feedback loops it has to the non- (or less-) damaged parts of the eco-system(s). These feedback loops are what enable adaptation and recovery.

Lastly, disaster response professionals cannot be every where at the same time. But the crowd is always there. Moreover, the vast majority of survivals following major disasters cannot be attributed to external aid. One study estimates that at most 10% of external aid contributes to saving lives. Why? Because the real first responders are the disaster-affected communities themselves, the local popula-tion. That is, the real first feedback loops are always local. This dynamic of mutual-aid facilitated by social media is certainly not new, however. My colleagues in Russia did this back in 2010 during the major forest fires that ravaged their country.

While I do have a bias towards people-centered interventions, this does not mean that I discount the importance of feedback loops to external actors such as traditional institutions and humanitarian organizations. I also don’t mean to romanticize the notion of “indigenous technical knowledge” or local coping mechanism. Some violate my own definition of human rights, for example. However, my bias stems from the fact that I am particularly interested in disaster resilience within the context of areas of limited statehood where said institutions and organizations are either absent are ineffective. But I certainly recognize the importance of scale jumping, particularly within the context of social capital and social media.

RESILIENCE THROUGH SOCIAL CAPITAL

Information-based feedback loops general social capital, and the latter has been shown to improve disaster resilience and recovery. In his recent book entitled “Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery,” Daniel Aldrich draws on both qualitative and quantitative evidence to demonstrate that “social resources, at least as much as material ones, prove to be the foundation for resilience and recovery.” His case studies suggest that social capital is more important for disaster resilience than physical and financial capital, and more important than conventional explanations. So the question that naturally follows given our interest in resilience & technology is this: can social media (which is not restricted by geography) influence social capital?

Building on Daniel’s research and my own direct experience in digital humani-tarian response, I argue that social media does indeed nurture social capital during disasters. “By providing norms, information, and trust, denser social networks can implement a faster recovery.” Such norms also evolve on Twitter, as does information sharing and trust building. Indeed, “social ties can serve as informal insurance, providing victims with information, financial help and physical assistance.” This informal insurance, “or mutual assistance involves friends and neighbors providing each other with information, tools, living space, and other help.” Again, this bonding is not limited to offline dynamics but occurs also within and across online social networks. Recall the sand pile analogy. Social capital facilitates the transformation of the sand pile away (temporarily) from self-organized criticality. On a related note vis-a-vis open source software, “the least important part of open source software is the code.” Indeed, more important than the code is the fact that open source fosters social ties, networks, communities and thus social capital.

(Incidentally, social capital generated during disasters is social capital that can subsequently be used to facilitate self-organization for non-violent civil resistance and vice versa).

RESILIENCE through big data

My empirical research on tweets posted during disasters clearly shows that while many use twitter (and social media more generally) to post needs during a crisis, those who are less affected in the social ecosystem will often post offers to help. So where does Big Data fit into this particular equation? When disaster strikes, access to information is equally important as access to food and water. This link between information, disaster response and aid was officially recognized by the Secretary General of the International Federation of Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies in the World Disasters Report published in 2005. Since then, disaster-affected populations have become increasingly digital thanks to the very rapid and widespread adoption of mobile technologies. Indeed, as a result of these mobile technologies, affected populations are increasingly able to source, share and generate a vast amount of information, which is completely transforming disaster response.

In other words, disaster-affected communities are increasingly becoming the source of Big (Crisis) Data during and following major disasters. There were over 20 million tweets posted during Hurricane Sandy. And when the major earth-quake and Tsunami hit Japan in early 2011, over 5,000 tweets were being posted every second. That is 1.5 million tweets every 5 minutes. So how can Big Data Analytics create more resilience in this respect? More specifically, how can Big Data Analytics accelerate disaster recovery? Manually monitoring millions of tweets per minute is hardly feasible. This explains why I often “joke” that we need a local Match.com for rapid disaster recovery. Thanks to social computing, artifi-cial intelligence, machine learning and Big Data Analytics, we can absolutely develop a “Match.com” for rapid recovery. In fact, I’m working on just such a project with my colleagues at QCRI. We are also developing algorithms to auto-matically identify informative and actionable information shared on Twitter, for example. (Incidentally, a by-product of developing a robust Match.com for disaster response could very well be an increase in social capital).

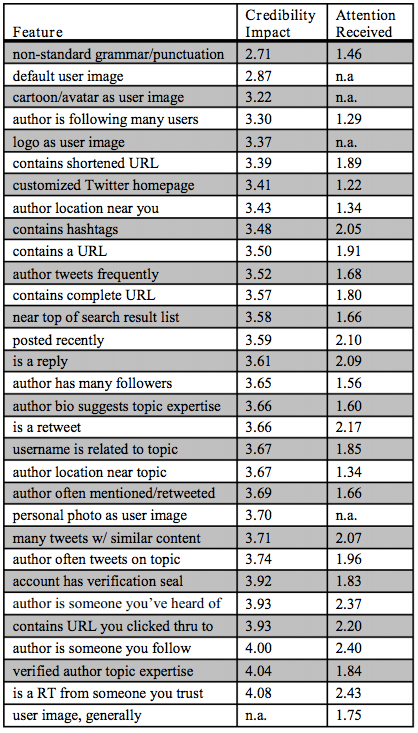

There are several other ways that advanced computing can create disaster resilience using Big Data. One major challenge is digital humanitarian response is the verification of crowdsourced, user-generated content. Indeed, misinforma-tion and rumors can be highly damaging. If access to information is tantamount to food access as noted by the Red Cross, then misinformation is like poisoned food. But Big Data Analytics has already shed some light on how to develop potential solutions. As it turns out, non-credible disaster information shared on Twitter propagates differently than credible information, which means that the credibility of tweets could be predicted automatically.

Conclusion

In sum, “resilience is the critical link between disaster and development; monitoring it [in real-time] will ensure that relief efforts are supporting, and not eroding […] community capabilities” (9). While the focus of this blog post has been on disaster resilience, I believe the insights provided are equally informa-tive for less extreme events. So I’d like to end on two major points. The first has to do with data philanthropy while the second emphasizes the critical importance of failing gracefully.

Big Data is Closed and Centralized

A considerable amount of “Big Data” is Big Closed and Centralized Data. Flow-minder’s study mentioned above draws on highly proprietary telecommunica-tions data. Facebook data, which has immense potential for humanitarian response, is also closed. The same is true of Twitter data, unless you have millions of dollars to pay for access to the full Firehose, or even Decahose. While access to the Twitter API is free, the number of tweets that can be downloaded and analyzed is limited to several thousand a day. Contrast this with the 5,000 tweets per second posted after the earthquake and Tsunami in Japan. We therefore need some serious political will from the corporate sector to engage in “data philanthropy”. Data philanthropy involves companies sharing proprietary datasets for social good. Call it Corporate Social Responsibility (CRS) for digital humanitarian response. More here on how this would work.

Failing Gracefully

Lastly, on failure. As noted, complex systems tend towards instability, i.e., self-organized criticality, which is why Homer-Dixon introduces the notion of failing gracefully. “Somehow we have to find the middle ground between dangerous rigidity and catastrophic collapse.” He adds that:

“In our organizations, social and political systems, and individual lives, we need to create the possibility for what computer programmers and disaster planners call ‘graceful’ failure. When a system fails gracefully, damage is limited, and options for recovery are preserved. Also, the part of the system that has been damaged recovers by drawing resources and information from undamaged parts.” Homer-Dixon explains that “breakdown is something that human social systems must go through to adapt successfully to changing conditions over the long term. But if we want to have any control over our direction in breakdown’s aftermath, we must keep breakdown constrained. Reducing as much as we can the force of underlying tectonic stresses helps, as does making our societies more resilient. We have to do other things too, and advance planning for breakdown is undoubtedly the most important.”

As Louis Pasteur famously noted, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” Preparing for breakdown is not defeatist or passive. Quite on the contrary, it is wise and pro-active. Our hubris—including our current infatuation with Bid Data—all too often clouds our better judgment. Like Macbeth, rarely do we seriously ask our-selves what we would do “if we should fail.” The answer “then we fail” is an option. But are we truly prepared to live with the devastating consequences of total synchronous failure?

In closing, some lingering (less rhetorical) questions:

- How can resilience can be measured? Is there a lowest common denominator? What is the “atom” of resilience?

- What are the triggers of resilience, creative capacity, local improvisation, regenerative capacity? Can these be monitored?

- Where do the concepts of “lived reality” and “positive deviance” enter the conversation on resilience?

- Is resiliency a right? Do we bear a responsibility to render systems more resilient? If so, recalling that resilience is the capacity to self-organize, do local communities have the right to self-organize? And how does this differ from democratic ideals and freedoms?

- Recent research in social-psychology has demonstrated that mindfulness is an amplifier of resilience for individuals? How can be scaled up? Do cultures and religions play a role here?

- Collective memory influences resilience. How can this be leveraged to catalyze more regenerative social systems?

Epilogue: Some colleagues have rightfully pointed out that resilience is ultima-tely political. I certainly share that view, which is why this point came up in recent conversations with my PopTech colleagues Andrew Zolli & Leetha Filderman. Readers of my post will also have noted my emphasis on distinguishing between hazards and disasters; that the latter are the product of social, economic and political processes. As noted in my blog post, there are no natural disasters. To this end, some academics rightly warn that “Resilience is a very technical, neutral, apolitical term. It was initially designed to characterize systems, and it doesn’t address power, equity or agency… Also, strengthening resilience is not free—you can have some winners and some losers.”

As it turns out, I have a lot say about the political versus technical argument. First of all, this is hardly a new or original argument but nevertheless an important one. Amartya Senn discussed this issue within the context of famines decades ago, noting that famines do not take place in democracies. In 1997, Alex de Waal published his seminal book, “Famine Crimes: Politics and the Disaster Relief In-dustry in Africa.” As he rightly notes, “Fighting famine is both a technical and political challenge.” Unfortunately, “one universal tendency stands out: technical solutions are promoted at the expense of political ones.” There is also a tendency to overlook the politics of technical actions, muddle or cover political actions with technical ones, or worse, to use technical measures as an excuse not to undertake needed political action.

De Waal argues that the use of the term “governance” was “an attempt to avoid making the political critique too explicit, and to enable a focus on specific technical aspects of government.” In some evaluations of development and humanitarian projects, “a caveat is sometimes inserted stating that politics lies beyond the scope of this study.” To this end, “there is often a weak call for ‘political will’ to bridge the gap between knowledge of technical measures and action to implement them.” As de Waal rightly notes, “the problem is not a ‘missing link’ but rather an entire political tradition, one manifestation of which is contemporary international humanitarianism.” In sum, “technical ‘solutions’ must be seen in the political context, and politics itself in the light of the domi-nance of a technocratic approach to problems such as famine.”

From a paper I presented back in 2007: “the technological approach almost always serves those who seek control from a distance.” As a result of this technological drive for pole position, a related “concern exists due to the separation of risk evaluation and risk reduction between science and political decision” so that which is inherently politically complex becomes depoliticized and mechanized. In Toward a Rational Society (1970), the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas describes “the colonization of the public sphere through the use of instrumental technical rationality. In this sphere, complex social problems are reduced to technical questions, effectively removing the plurality of contending perspectives.”

To be sure, Western science tends to pose the question “How?” as opposed to “Why?”What happens then is that “early warning systems tend to be largely conceived as hazard-focused, linear, topdown, expert driven systems, with little or no engagement of end-users or their representatives.” As De Waal rightly notes, “the technical sophistication of early warning systems is offset by a major flaw: response cannot be enforced by the populace. The early warning information is not normally made public.” In other words, disaster prevention requires “not merely identifying causes and testing policy instruments but building a [social and] political movement” since “the framework for response is inherently political, and the task of advocacy for such response cannot be separated from the analytical tasks of warning.”

Recall my emphasis on people-centered early warning above and the definition of resilience as capacity for self-organization. Self-organization is political. Hence my efforts to promote greater linkages between the fields of nonviolent action and early warning years ago. I have a paper (dated 2008) specifically on this topic should anyone care to read. Anyone who has read my doctoral dissertation will also know that I have long been interested in the impact of technology on the balance of power in political contexts. A relevant summary is available here. Now, why did I not include all this in the main body of my blog post? Because this updated section already runs over 1,000 words.

In closing, I disagree with the over-used criticism that resilience is reactive and about returning to initial conditions. Why would we want to be reactive or return to initial conditions if the latter state contributed to the subsequent disaster we are recovering from? When my colleague Andrew Zolli talks about resilience, he talks about “bouncing forward”, not bouncing back. This is also true of Nassim Taleb’s term antifragility, the ability to thrive on disruption. As Homer-Dixon also notes, preparing to fail gracefully is hardly reactive either.