Authored by Kate Crawford, Patrick Meier, Claudia Perlich, Amy Luers, Gustavo Faleiros and Jer Thorp, 2013 PopTech & Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Fellows.

Update: See also “Big Data, Communities and Ethical Resilience: A Framework for Action” written by the above Fellows and available here (PDF).

The following is a draft “Code of Conduct” that seeks to provide guidance on best practices for resilience building projects that leverage Big Data and Advanced Computing. These seven core principles serve to guide data projects to ensure they are socially just, encourage local wealth- & skill-creation, require informed consent, and be maintainable over long timeframes. This document is a work in progress, so we very much welcome feedback. Our aim is not to enforce these principles on others but rather to hold ourselves accountable and in the process encourage others to do the same. Initial versions of this draft were written during the 2013 PopTech & Rockefeller Foundation workshop in Bellagio, August 2013.

1. Open Source Data Tools

Wherever possible, data analytics and manipulation tools should be open source, architecture independent and broadly prevalent (R, python, etc.). Open source, hackable tools are generative, and building generative capacity is an important element of resilience. Data tools that are closed prevent end-users from customizing and localizing them freely. This creates dependency on external experts which is a major point of vulnerability. Open source tools generate a large user base and typically have a wider open knowledge base. Open source solutions are also more affordable and by definition more transparent. Open Data Tools should be highly accessible and intuitive to use by non-technical users and those with limited technology access in order to maximize the number of participants who can independently use and analyze Big Data.

2. Transparent Data Infrastructure

Infrastructure for data collection and storage should operate based on transparent standards to maximize the number of users that can interact with the infrastructure. Data infrastructure should strive for built-in documentation, be extensive and provide easy access. Data is only as useful to the data scientist as her/his understanding of its collection is correct. This is critical for projects to be maintained over time, regardless of team membership, otherwise projects will collapse when key members leave. To allow for continuity, the infrastructure has to be transparent and clear to a broad set of analysts – independent of the tools they bring to bear. Solutions such as hadoop, JSON formats and the use of clouds are potentially suitable.

3. Develop and Maintain Local Skills

Make “Data Literacy” more widespread. Leverage local data labor and build on existing skills. The key and most constraint ingredient to effective data solutions remains human skill/knowledge and needs to be retained locally. In doing so, consider cultural issues and language. Catalyze the next generation of data scientists and generate new required skills in the cities where the data is being collected. Provide members of local communities with hands-on experience; people who can draw on local understanding and socio-cultural context. Longevity of Big Data for Resilience projects depends on the continuity of local data science teams that maintain an active knowledge and skills base that can be passed on to other local groups. This means hiring local researchers and data scientists and getting them to build teams of the best established talent, as well as up-and-coming developers and designers. Risks emerge when non-resident companies are asked to spearhead data programs that are connected to local communities. They bring in their own employees, do not foster local talent over the long-term, and extract value from the data and the learning algorithms that are kept by the company rather than the local community.

4. Local Data Ownership

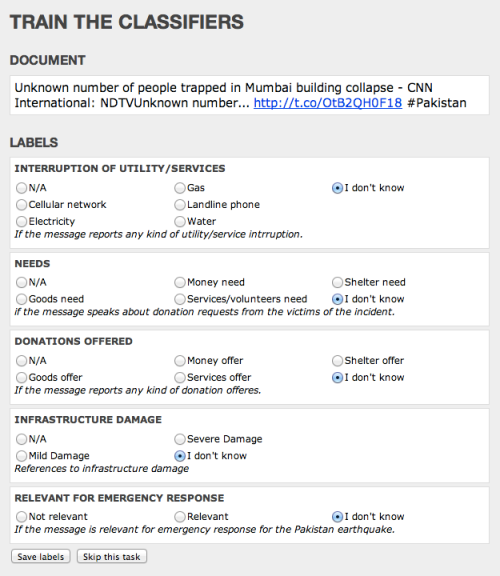

Use Creative Commons and licenses that state that data is not to be used for commercial purposes. The community directly owns the data it generates, along with the learning algorithms (machine learning classifiers) and derivatives. Strong data protection protocols need to be in place to protect identities and personally identifying information. Only the “Principle of Do No Harm” can trump consent, as explicitly stated by the International Committee of the Red Cross’s Data Protection Protocols (ICRC 2013). While the ICRC’s data protection standards are geared towards humanitarian professionals, their core protocols are equally applicable to the use of Big Data in resilience projects. Time limits on how long the data can be used for should be transparently stated. Shorter frameworks should always be preferred, unless there are compelling reasons to do otherwise. People can give consent for how their data might be used in the short to medium term, but after that, the possibilities for data analytics, predictive modelling and de-anonymization will have advanced to a state that cannot at this stage be predicted, let alone consented to.

5. Ethical Data Sharing

Adopt existing data sharing protocols like the ICRC’s (2013). Permission for sharing is essential. How the data will be used should be clearly articulated. An opt in approach should be the preference wherever possible, and the ability for individuals to remove themselves from a data set after it has been collected must always be an option. Projects should always explicitly state which third parties will get access to data, if any, so that it is clear who will be able to access and use the data. Sharing with NGOs, academics and humanitarian agencies should be carefully negotiated, and only shared with for-profit companies when there are clear and urgent reasons to do so. In that case, clear data protection policies must be in place that will bind those third parties in the same way as the initial data gatherers. Transparency here is key: communities should be able to see where their data goes, and a complete list of who has access to it and why.

6. Right Not To Be Sensed

Local communities have a right not to be sensed. Large scale city sensing projects must have a clear framework for how people are able to be involved or choose not to participate. All too often, sensing projects are established without any ethical framework or any commitment to informed consent. It is essential that the collection of any sensitive data, from social and mobile data to video and photographic records of houses, streets and individuals, is done with full public knowledge, community discussion, and the ability to opt out. One proposal is the #NoShare tag. In essence, this principle seeks to place “Data Philanthropy” in the hands of local communities and in particular individuals. Creating clear informed consent mechanisms is a requisite for data philanthropy.

7. Learning from Mistakes

Big Data and Resilience projects need to be open to face, report, and discuss failures. Big Data technology is still very much in a learning phase. Failure and the learning and insights resulting from it should be accepted and appreciated. Without admitting what does not work we are not learning effectively as a community. Quality control and assessment for data-driven solutions is notably harder than comparable efforts in other technology fields. The uncertainty about quality of the solution is created by the uncertainty inherent in data. Even good data scientist are struggling to assess the upside potential of incremental efforts on the quality of a solution. The correct analogy is more one a craft rather a science. Similar to traditional crafts, the most effective way is to excellence is to learn from ones mistakes under the guidance of a mentor with a collective knowledge of experiences of both failure and success.