I just had the pleasure of speaking with my new colleague Jakob Rogstadius from Madeira Interactive Technologies Institute (Madeira-TTI). Jakob is working on CrisisTracker, a very interesting platform designed to facilitate collaborative social media analysis for disaster response. The rationale for CrisisTracker is the same one behind Ushahidi’s SwiftRiver project and could be hugely helpful for crisis mapping projects carried out by the Standby Volunteer Task Force (SBTF).

From the CrisisTracker website:

“During large-scale complex crises such as the Haiti earthquake, the Indian Ocean tsunami and the Arab Spring, social media has emerged as a source of timely and detailed reports regarding important events. However, indivi-dual disaster responders, government officials or citizens who wish to access this vast knowledge base are met with a torrent of information that quickly results in information overload. Without a way to organize and navigate the reports, important details are easily overlooked and it is challenging to use the data to get an overview of the situation as a whole.”

We (Madeira University, University of Oulu and IBM Research) believe that volunteers around the world would be willing to assist hard-pressed decision makers with information management, if the tools were available. With this vision in mind, we have developed Crisis-Tracker.”

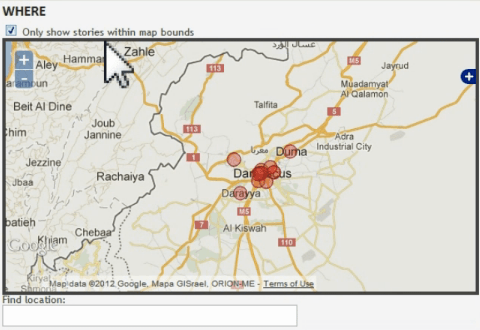

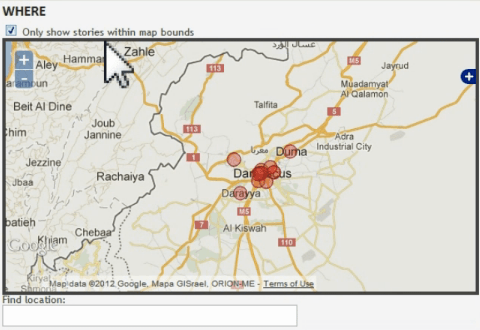

Like SwiftRiver, CrisisTracker combines some automated clustering of content with the crowdsourced curation of said content for further filtering. “Any user of the system can directly contribute tags that make it easier for other users to retrieve information and explore stories by similarity. In addition, users of the system can influence how tweets are grouped into stories.” Stories can be filtered by Report Category, Keywords, Named Entities, Time and Location. CrisisTracker also allows for simple geo-fencing to capture and list only those Tweets displayed on a given map.

Geolocation, Report Categories and Named Entities are all generated manually. The clustering of reports into stories is done automatically using keyword frequencies. So if keyword dictionaries exist for other languages, the platform could be used in these other languages as well. The result is a list of clustered Tweets displayed below the map, with the most popular cluster at the top.

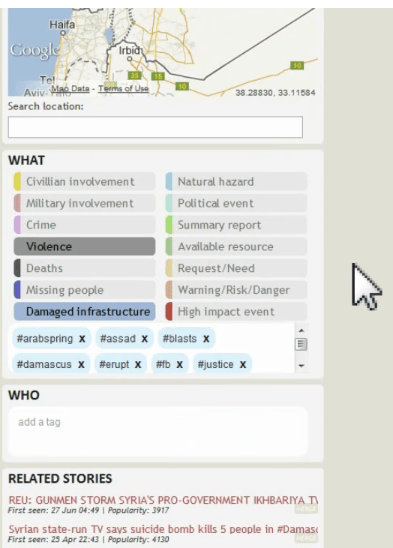

Clicking on an entry like the row in red above opens up a new page, like the one below. This page lists a group of tweets that all discuss the same specific event, in this case an explosion in Syria’s capital.

What is particularly helpful about this setup is the meta-data displayed for this story or event: the number of people who tweeted about the story, the number of tweets about the story, the first day/time the story was shared on twitter. In addition, the first tweet to report the story is listed along, which is very helpful. This list can be ranked according to “Size” which is a figure that reflects the minimum number of original tweets and the number of Twitter users who shared these tweets. This is a particularly useful metric (and way to deal with spammers). Users also have the option of listing the first 50 tweets that referenced the story.

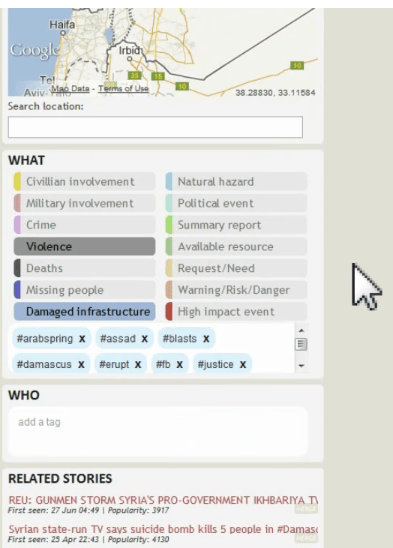

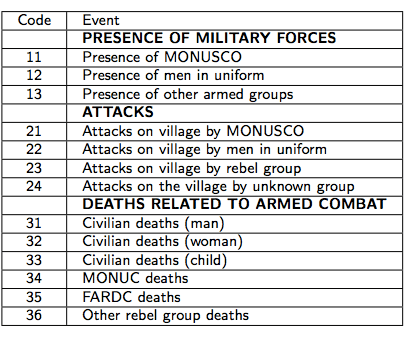

As you may be able to tell from the “Hide Story” and “Remove” buttons on the righthand-side of the display above, each clustered story and indeed tweet can be hidden or removed if not relevant. This is where crowdsourced curation comes in. In addition, CrisisTracker enable users to geo-tag and categorize each tweets according to report type (e.g., Violence, Deaths, Request/Need, etc.), general keywords (e.g., #assad, #blasts, etc.) and named entities. Note the the keywords can be removed and more high-quality tags can be added or crowdsourced by users as well (see below).

CrisisTracker also suggests related stories that may be of interest to the user based on the initial clustering and filtering—assisted manual clustering. In addition, the platform’s API means that the data can then be exported in XML using a simple parser. So interoperability with platforms like Ushahidi’s would be possible. After our call, Jakob added a link on each story page in the system (a small XML icon below the related stories) to get the story in XML format. Any other system can now take this URL and parse the story into its own native format. Jakob is also looking to build a number of extensions to CrisisTracker and a “Share with Ushahidi” button may be one such future extension. Crisis-Tracker is basically Jakob’s core PhD project, which is very cool, so he’ll be working on this for at least one more year.

In sum, this could very well be the platform that many of us in the crisis mapping space have been waiting for. As I wrote in February 2012, turning the Twitter-sphere “into real-time shared awareness will require that our filtering and curation platforms become more automated and collaborative. I believe the key is thus to combine automated solutions with real-time collaborative crowd-sourcing tools—that is, platforms that enable crowds to collaboratively filter and curate real-time information, in real-time. Right now, when we comb through Twitter, for example, we do so on our own, sitting behind our laptop, isolated from others who may be seeking to filter the exact same type of content. We need to develop free and open source platforms that allow for the distributed-but-networked, crowdsourced filtering and curation of information in order to democratize the sense-making of the firehose.”

Actually, I’ve been advocating for this approach since early 2009. So I’m really excited about Jakob’s project. We’ll be partnering with him and the Standby Volunteer Task Force (SBTF) in September 2012 to test the platform and provide him with expert feedback on how to further streamline the tool for collaborative social media analysis and crisis mapping. Jakob is also looking for domain experts to help on this study. In the meantime, I’ve invited Jakob to present Crisis-Tracker at the 2012 CrisisMappers Conference in Washington DC and very much hope he can join us to demo his tool to us in person. In the meantime, the video above provides an excellent overview of CrisisTracker, as does the project website. Finally, the project is also open source and available on Github here.

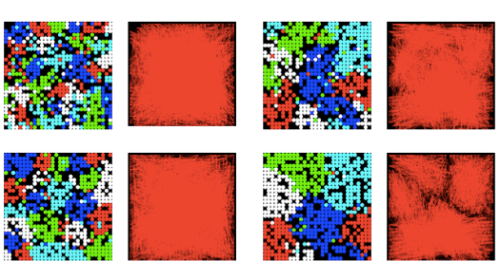

Epilogue: The main problem with CrisisTracker is that it is still too manual; it does not include any machine learning & artificial intelligence features; and has only focused on Syria. This may explain why it has not gained traction in the humanitarian space so far.