Aéroport de Port Vila – Bauerfield International Airport. As we land, thousands of uprooted trees could be seen in almost every direction.

Massive roots were not enough to save these trees from Cyclone Pam. The devastation reminds us how powerful nature is.

After getting clearance from the Australian Defense Force (ADF), we pack up our UAVs and head over to La Lagune for initial tests. Close collaboration with the military is an absolute must for humanitarian UAV missions. UAVs cannot operate in Restricted Operations Zones without appropriate clearance.

We’re in Vanuatu by invitation of the Government’s National Disaster Risk Management Office (NDMO). So we’re working very closely with our hosts to assess disaster damage and resulting needs. The government and donors need the damage quantified to assess how much funding is necessary for the recovery efforts; and where geographically that funding should be targeted.

Ceci n’est pas un drone; what we found at La Lagune, where the ADF has set up camp. At 2200 every night we send the ADF our flight plan clearance requests for the following day. For obvious safety reasons, we never deviate from these plans after they’ve been approved.

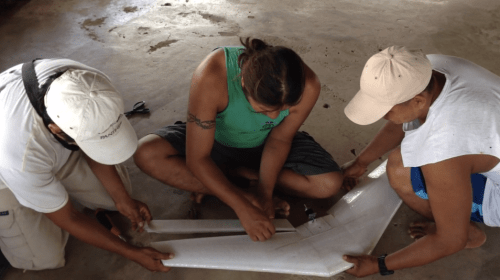

Unpacking and putting together the hexacopters can take a long time. The professional and certified UAV team from New Zealand (X-Craft) follows strict operational check lists to ensure safety and security. We also have a professional and certified team from Australia, Heliwest, which will be flying quadcopters. The UAV team from SPC is also joining our efforts. I’m proud to report that both the Australian & New Zealand teams were recruited directly from the pilot roster of the Humanitarian UAV Network.

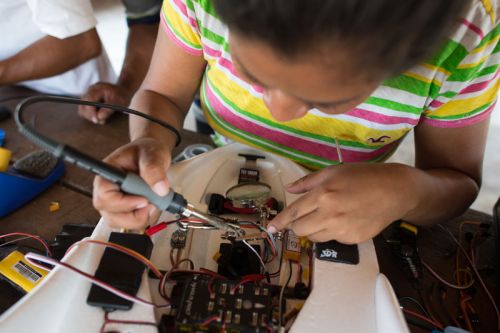

The payload (camera) attached to our hexacopters; not exactly a GoPro. We also have other sensors for thermal imaging, etc.

Programming the test flights. Here’s a quick video intro on how to program UAVs for autonomous flights.

Night falls fast in Vanuatu…

… So our helpful drivers kindly light up our work area.

After flawless test flights; we’re back at “HQ” to program the flight paths for tomorrow morning’s humanitarian UAV missions. The priority survey areas tend to change on a daily basis as the government gets more information on which outlying islands have been hardest hit. Our first mission will focus on an area comprised of informal settlements.

Dawn starts to break at 0500. We haven’t gotten much sleep.

At 0600, we arrive at the designated meeting point, the Beach Bar. This will be our base of operations for this morning’s mission.

The flight plans for the hexacopters are ready to go. We have clearance from Air Traffic Control (ATC) to fly until 0830 as manned aircraft start operating extensively after 0900. So in complex airspaces like this one in Vanuatu’s Port Vila, we only fly very early in the morning and after 1700 in the evening. We have ATC’s direct phone number and are in touch with the tower at all times.

Could this be the one and only SXSW 2015 bag in Vanuatu?

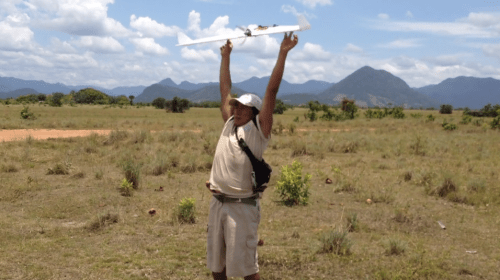

All our multirotor UAVs have been tested once again and are now ready to go. The government has already communicated to nearby villages that UAVs will be operating between 0630-0830. We aim to collect aerial imagery at a resolution of 4cm-6cm throughout our missions.

An old basketball court; perfect for take-off & landing.

And of course, when we’re finally ready to fly, it starts to pour. Other challenges include an ash cloud from a nearby volcano. We’ve also been told that kids here are pro’s with slingshots (which is one reason why the government informed local villagers of the mission; i.e., to request that kids not use the UAVs for target practice).

After some delays, we are airborne at last.

Operating the UAViators DJI Phantom…

… Which I’m using purely for documentary purposes. In coming days, we’ll be providing our government partners with a hands-on introduction on how to operate Phantom II’s. Building local capacity is key; which is why this action item is core to the Humanitarian UAV Network’s Code of Conduct.

Can you spot the hexacopter? While there’s only one in the picture below, we actually have two in the air at different altitudes which we are operating by Extended Line of Site and First Person View as a backup.

More aerial shots I took using the Phantom (not for damage assessment; simply for documentary purposes).

Can you spot the basketball court?

Large clouds bring back the rain; visibility is reduced. We have to suspend our flights; will try again after 1700.

Meanwhile, my Phantom’s GoPro snaps this close up picture on landing.

Stay tuned for updates and in particular the very high resolution aerial imagery that we’ll be posting to MapBox in coming days; along with initial analysis carried out by multiple partners including Humanitarian OpenStreetMap (HOT) and QCRI‘s MicroMappers. Many thanks to MapBox for supporting our efforts. We will also be overlaying the aerial imagery analysis over this MicroMappers crisis map of ground-based pictures of disaster damage in order to triangulate the damage assessment results. Check out the latest update here.

In the meantime, more information on this Humanitarian UAV Mission to Vanuatu–spearheaded by the World Bank in very close collaboration with the Government and SPC–can be found on the Humanitarian UAV Network (UAViators) Ops page here. UAViators is an initiative I launched at QCRI following Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in 2013. More on UAViators and the use of humanitarian UAVs in my new book Digital Humanitarians.

Important: this blog post is a personal update written in my personal capacity; none of the above is in any way shape or form a formal communique or press release by any of the partners. Official updates will be provided by the Government of Vanuatu and World Bank directly. Please contact me here for official media requests; kindly note that my responses will need to be cleared by the Government & Bank first.