Sarah Vieweg‘s doctoral dissertation from the University of Colorado is a must-read for anyone interested in the use of twitter during crises. I read the entire 300-page study because it provides important insights on how automated natural language processing (NLP) can be applied to the Twittersphere to provide situational awareness following a sudden-onset emergency. Big thanks to Sarah for sharing her dissertation with QCRI. I include some excerpts below to highlight the most important findings from her excellent research.

Introduction

“In their research on human behavior in disaster, Fritz and Marks (1954) state: ‘[T]he immediate problem in a disaster situation is neither un-controlled behavior nor intense emotional reaction, but deficiencies of coordination and organization, complicated by people acting upon individual…definitions of the situation.'”

“Fritz and Marks’ assertion that people define disasters individually, which can lead to problematic outcomes, speaks to the need for common situational awareness among affected populations. Complete information is not attained during mass emergency, else it would not be a mass emergency. However, the more information people have and the better their situational awareness, and the better equipped they are to make tactical, strategic decisions.”

“[D]uring crises, people seek information from multiple sources in an attempt to make locally optimal decisions within given time constraints. The first objective, then, is to identify what tweets that contribute to situational awareness ‘look like’—i.e. what specific information do they contain? This leads to the next objective, which is to identify how information is communicated at a linguistic level. This process provides the foundation for tools that can automatically extract pertinent, valuable information—training machines to correctly ‘understand’ human language involves the identification of the words people use to communicate via Twitter when faced with a disaster situation.”

Research Design & Results

Just how much situational awareness can be extracted from twitter during a crisis? What constitutes situational awareness in the first place vis-a-vis emergency response? And can the answer to these questions yield a dedicated ontology that can be fed into automated natural language processing platforms to generate real-time, shared awareness? To answer these questions, Sarah analyzed four emergency events: Oklahoma Fires (2009), Red River Floods (2009 & 2010) and the Haiti Earthquake (2010).

She collected tweets generated during each of these emergencies and developed a three-step qualitative coding process to analyze what kinds of information on Twitter contribute to situational awareness during a major emergency. As a first step, each tweet was categorized as either:

O: Off-topic

“Tweets do not contain any information that mentions or relates to the emergency event.”

R: On-topic and Relevant to Situational Awareness

“Tweets contain information that provides tactical, actionable information that can aid people in making decisions, advise others on how to obtain specific information from various sources, or offer immediate post- impact help to those affected by the mass emergency.”

N: On-topic and Not Relevant to Situational Awareness

“Tweets are on-topic because they mention the emergency by including offers of prayer and support in relation to the emergency, solicitations for donations to charities, or casual reference to the emergency event. But these tweets do not meet the above criteria for situational relevance.”

The O, R, and N coding of the crisis datasets resulted in the following statistics for each of the four datasets:

For the second coding step, on-topic relevant tweets were annotated with more specific information based on the following coding rule:

S: Social Environment

“These tweets include information about how people and/or animals are affected by a hazard, questions asked in relation to the hazard, responses to the hazard and actions to take that directly relate to the hazard and the emergency situation it causes. These tweets all include description of a human element in that they explain or display human behavior.”

B: Built Environment

“Tweets that include information about the effect of the hazard on the built environment, including updates on the state of infrastructure, such as road closures or bridge outages, damage to property, lack of damage to property and the overall state or condition of structures.”

P: Physical Environment

“Tweets that contain specific information about the hazard including particular locations of the hazard agent or where the hazard agent is expected or predicted to travel or predicted states of the hazard agent going forward, notes about past hazards that compare to the current hazard, and how weather may affect hazard conditions. These tweets additionally include information about the type of hazard in general […]. This category also subsumes any general information about the area under threat or in the midst of an emergency […].”

The result of this coding for Haiti is depicted in the figures below.

According to the results, the social environment (‘S’) category is most common in each of the datasets. “Disasters are social events; in each disaster studied in this dissertation, the disaster occurred because a natural hazard impacted a large number of people.”

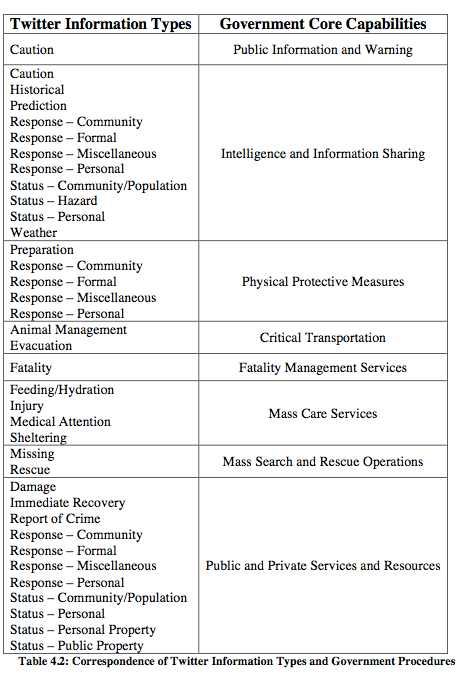

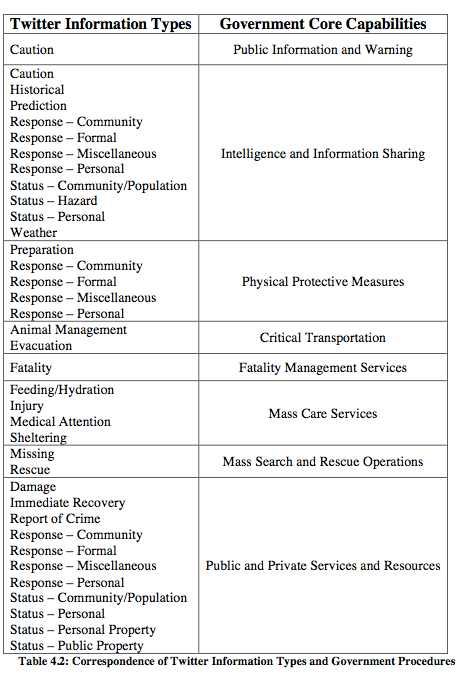

For the third coding step, Sarah created a comprehensive list of several dozen “Information Types” for each “Environment” using inductive, data-driven analysis of twitter communications, which she combined with findings from the disaster literature and official government procedures for disaster response. In total, Sarah identified 32 specific types of information that contribute to situational awareness. The table below compares the Twitter Information Types for all three environments as related to government procedures, for example.

“Based on the discourse analysis of Twitter communications broadcast during four mass emergency events,” Sarah identified 32 specific types of information that “contribute to situational awareness. Subsequent analysis of the sociology of disaster literature, government documents and additional research on the use of Twitter in mass emergency uncovered three additional types of information.”

In sum, “[t]he comparison of the information types [she] uncovered in [her] analysis of Twitter communications to sociological research on disaster situations, and to governmental procedures, serves as a way to gauge the validity of [her] ground-up, inductive analysis.” Indeed, this enabled Sarah to identify areas of overlap as well as gaps that needed to be filled. The final Information Type framework is listed below:

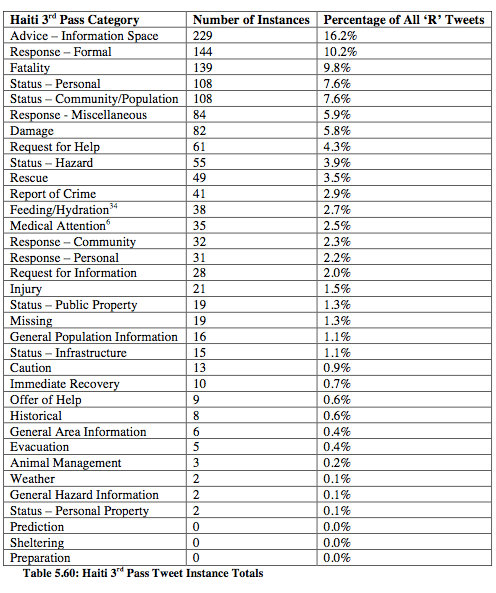

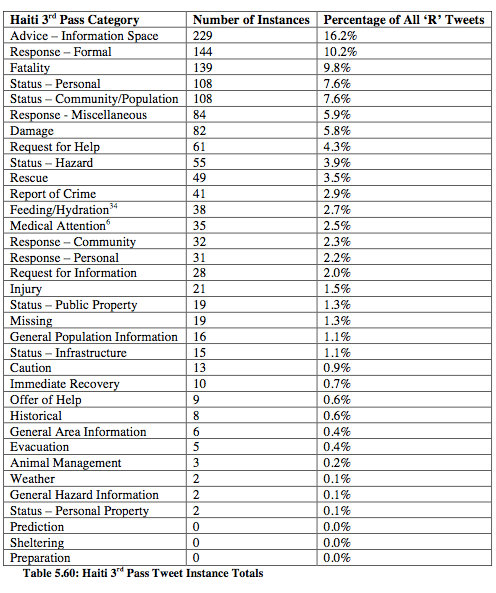

And here are the results of this coding framework when applied to the Haiti data:

“Across all four datasets, the top three types of information Twitter users communicated comprise between 36.7-52.8% of the entire dataset. This is an indication that though Twitter users communicate about a variety of informa-tion, a large portion of their attention is focused on only a few types of in-formation, which differ across each emergency event. The maximum number of information types communicated during an event is twenty-nine, which was during the Haiti earthquake.”

Natural Language Processing & Findings

The coding described above was all done manually by Sarah and research colleagues. But could the ontology she has developed (Information Types) be used to automatically identify tweets that are both on-topic and relevant for situational awareness? To find out, she carried out a study using VerbNet.

“The goal of identifying verbs used in tweets that convey information relevant to situational awareness is to provide a resource that demonstrates which VerbNet classes indicate information relevant to situational awareness. The VerbNet class information can serve as a linguistic feature that provides a classifier with information to identify tweets that contain situational awareness information. VerbNet classes are useful because the classes provide a list of verbs that may not be present in any of the Twitter data I examined, but which may be used to describe similar information in unseen data. In other words, if a particular VerbNet class is relevant to situational awareness, and a classifier identifies a verb in that class that is used in a previously unseen tweet, then that tweet is more likely to be identified as containing situational awareness information.”

Sarah identified 195 verbs that mapped to her Information Types described earlier. The results of using this verb-based ontology are mixed, however. “A majority of tweets do not contain one of the verbs in the identified VerbNet classes, which indicates that additional features are necessary to classify tweets according to the social, built or physical environment.”

However, when applying the 195 verbs to identify on-topic tweets relevant to situational awareness to previously unused Haiti data, Sarah found that using her customized VerbNet ontology resulted in finding 9% more tweets than when using her “Information Types” ontology. In sum, the results show that “using VerbNet classes as a feature is encouraging, but other features are needed to identify tweets that contain situational awareness information, as not all tweets that contain situational awareness information use one of the verb members in the […] identified VerbNet classes. In addition, more research in this area will involve using the semantic and syntactic information contained in each VerbNet class to identify event participants, which can lead to more fine-grained categorization of tweets.”

Conclusion

“Many tweets that communicate situational awareness information do not contain one of the verbs in the identified VerbNet classes, [but] the information provided with named entities and semantic roles can serve as features that classifiers can use to identify situational awareness information in the absence of such a verb. In addition, for tweets correctly identified as containing information relevant to situational awareness, named entities and semantic roles can provide classifiers with additional information to classify these tweets into the social, built and physical environment categories, and into specific information type categories.”

“Finding the best approach toward the automatic identification of situational awareness information communicated in tweets is a task that will involve further training and testing of classifiers.”

![]()