Friends Peter van der Windt and Gregory Asmolov are two of the sharpest minds I know when it comes to crowdsourcing crisis information and crisis response. So it was a real treat to catch up with them in Berlin this past weekend during the “ICTs in Limited Statehood” workshop. An edited book of the same title is due out next year and promises to be an absolute must-read for all interested in the impact of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) on politics, crises and development.

I blogged about Gregory’s presentation following last year’s workshop, so this year I’ll relay Peter’s talk on research design and methodology vis-a-vis the collection of security incidents in conflict environments using SMS. Peter and mentor Macartan Humphreys completed their Voix des Kivus project in the DRC last year, which ran for just over 16 months. During this time, they received 4,783 text messages on security incidents using the FrontlineSMS platform. These messages were triaged and rerouted to several NGOs in the Kivus as well as the UN Mission there, MONUSCO.

How did they collect this information in the first place? Well, they considered crowdsourcing but quickly realized this was the wrong methodology for their project, which was to assess the impact of a major conflict mitigation program in the region. (Relaying text messages to various actors on the ground was not initially part of the plan). They needed high-quality, reliable, timely, regular and representative conflict event-data for their monitoring and evaluation project. Crowdsourcing is obviously not always the most appropriate methodology for the collection of information—as explained in this blog post.

Peter explained the pro’s and con’s of using crowdsourcing by sharing the framework above. “Knowledge” refers to the fact that only those who have knowledge of a given crowdsourcing project will know that participating is even an option. “Means” denotes whether or not an individual has the ability to participate. One would typically need access to a mobile phone and enough credit to send text messages to Voix des Kivus. In the case of the DRC, the size of subset “D” (no knowledge / no means) would easily dwarf the number of individuals comprising subset “A” (knowledge / means). In Peter’s own words:

“Crowdseeding brings the population (the crowd) from only A (what you get with crowdsourcing) to A+B+C+D: because you give phones&credit and you go to and inform the phoneholds about the project. So the crowd increases from A to A+B+C+D. And then from A+B+C+D one takes a representative sample. So two important benefits. And then a third: the relationship with the phone holder: stronger incentive to tell the truth, and no bad people hacking into the system.”

In sum, Peter and Macartan devised the concept of “crowdseeding” to increase the crowd and render that subset a representative sample of the overall population. In addition, the crowdseeding methodology they developed genera-ted more reliable information than crowdsourcing would have and did so in a way that was safer and more sustainable.

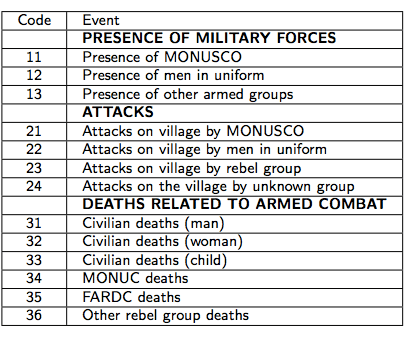

Peter traveled to 18 villages across the Kivus and in each identified three representatives to serve as the eyes and years of the village. These representatives were selected in collaboration with the elders and always included a female representative. They were each given a mobile phone and received extensive training. A code book was also shared which codified different types of security incidents. That way, the reps simply had to type the number corresponding to a given incident (or several numbers if more than one incident had taken place). Anyone in the village could approach these reps with relevant information which would then be texted to Peter and Macartan.

The table above is the first page of the codebook. Note that the numerous security risks of doing this SMS reporting were discussed at length with each community before embarking on the selection of 3 village reps. Each community decided to voted to participate despite the risks. Interestingly, not a single village voted against launching the project. However, Peter and Macartan chose not to scale the project beyond 18 villages for fear that it would get the attention of the militias operating in the region.

A local field representative would travel to the villages every two weeks or so to individually review the text messages sent out by each representative and to verify whether these incidents had actually taken place by asking others in the village for confirmation. The fact that there were 3 representatives per village also made the triangulation of some text messages possible. Because the 18 villages were randomly selected as part the randomized control trial (RCT) for the monitoring and evaluation project, the text messages were relaying a representative sample of information.

But what was the incentive? Why did a total of 54 village representatives from 18 villages send thousands of text messages to Voix des Kivus over a year and a half? On the financial side, Peter and Macartan devised an automated way to reimburse the cost of each text message sent on a monthly basis and in addition provided an additional $1.5/month. The only ask they made of the reps was that each had to send at least one text message per week, even if that message had the code 00 which referred to “no security incident”.

The figure above depicts the number of text messages received throughout the project, which formally ended in January 2011. In Peter’s own words:

“We gave $20 at the end to say thanks but also to learn a particular thing. During the project we heard often: ‘How important is that weekly $1.5?’ ‘Would people still send messages if you only reimburse them for their sent messages (and stop giving them the weekly $1.5)?’ So at the end of the project […] we gave the phone holder $20 and told them: the project continues exactly the same, the only difference is we can no longer send you the $1.5. We will still reimburse you for the sent messages, we will still share the bulletins, etc. While some phone holders kept on sending textmessages, most stopped. In other words, the financial incentive of $1.5 (in the form of phonecredit) was important.”

Peter and Macartan have learned a lot during this project, and I urge colleagues interested in applying their project to get in touch with them–I’m happy to provide an email introduction. I wish Swisspeace’s Early Warning System (FAST) had adopted this methodology before running out of funding several years ago. But the leadership at the time was perhaps not forward thinking enough. I’m not sure whether the Conflict Early Warning and Response Network (CEWARN) in the Horn has fared any better vis-a-vis demonstrated impact or lack thereof.

To learn more about crowdsourcing as a methodology for information collection, I recommend the following three articles: