Those who are still skeptical about the value of Twitter for real-time situational awareness during a crisis ought to ask why terrorists likely think otherwise. In 2008, terrorists carried out multiple attacks on Mumbai in what many refer to as the worst terrorist incident in Indian history. This study, summarized below, explains how the terrorists in question could have used social media for coor-dination and decision-making purposes.

The study argues that “the situational information which was broadcast through live media and Twitter contributed to the terrorists’ decision making process and, as a result, it enhanced the effectiveness of hand-held weapons to accomplish their terrorist goal.” To be sure, the “sharing of real time situational information on the move can enable the ‘sophisticated usage of the most primitive weapons.'” In sum, “unregulated real time Twitter postings can contribute to increase the level of situation awareness for terrorist groups to make their attack decision.”

According to the study, “an analysis of satellite phone conversations between terrorist commandos in Mumbai and remote handlers in Pakistan shows that the remote handlers in Pakistan were monitoring the situation in Mumbai through live media, and delivered specific and situational attack commands through satellite phones to field terrorists in Mumbai.” These conversations provide “evidence that the Mumbai terrorist groups understood the value of up-to-date situation information during the terrorist operation. […] They under-stood that the loss of information superiority can compromise their operational goal.”

Handler: See, the media is saying that you guys are now in room no. 360 or 361. How did they come to know the room you guys are in?…Is there a camera installed there? Switch off all the lights…If you spot a camera, fire on it…see, they should not know at any cost how many of you are in the hotel, what condition you are in, where you are, things like that… these will compromise your security and also our operation […]

Terrorist: I don’t know how it happened…I can’t see a camera anywhere.

A subsequent phone conversation reveals that “the terrorists group used the web search engine to increase their decision making quality by employing the search engine as a complement to live TV which does not provide detailed information of specific hostages. For instance, to make a decision if they need to kill a hostage who was residing in the Taj hotel, a field attacker reported the identity of a hostage to the remote controller, and a remote controller used a search engine to obtain the detailed information about him.”

Terrorist: He is saying his full name is K.R.Ramamoorthy.

Handler: K.R. Ramamoorthy. Who is he? … A designer … A professor … Yes, yes, I got it …[The caller was doing an internet search on the name, and a results showed up a picture of Ramamoorthy] … Okay, is he wearing glasses? [The caller wanted to match the image on his computer with the man before the terrorists.]

Terrorist: He is not wearing glasses. Hey, … where are your glasses?

Handler: … Is he bald from the front?

Terrorist: Yes, he is bald from the front …

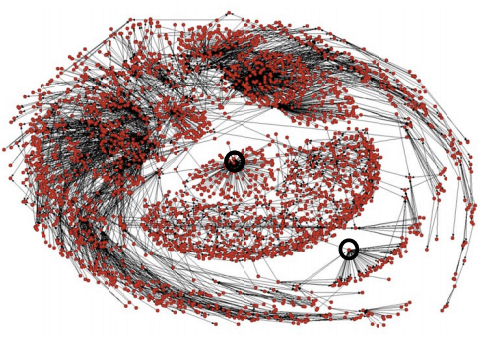

The terrorist group had three specific political agendas: “(1) an anti-India agenda, (2) an anti-Israel and anti-Jewish agenda, and (3) an anti-US and anti-Nato agenda.” A content analysis of 900+ tweets posted during the attacks reveal whether said tweets may have provided situational awareness information in support of these three political goals. The results: 18% of tweets contained “situa-tional information which can be helpful for Mumbai terrorist groups to make an operational decision of achieving their Anti-India political agenda. Also, 11.34% and 4.6% of posts contained operationally sensitive information which may help terrorist groups to make an operational decision of achieving their political goals of Anti-Israel/Anti-Jewish and Anti-US/Anti-Nato respectively.”

In addition, the content analysis found that “Twitter site played a significant role in relaying situational information to the mainstream media, which was monitored by Mumbai terrorists. Therefore, we conclude that the Mumbai Twitter page in-directly contributed to enhancing the situational awareness level of Mumbai terrorists, although we cannot exclude the possibility of its direct contribution as well.”

In conclusion, the study stresses the importance analyzing a terrorist group’s political goals in order to develop an appropriate information control strategy. “Because terrorists’ political goals function as interpretative filters to process situational information, understanding of adversaries’ political goals may reduce costs for security operation teams to monitor and decide which tweets need to be controlled.”

See also: Analyzing Tweets Posted During Mumbai Terrorist Attacks [Link]