“What is the optimal spatial resolution for the analysis of disaster damage?”

I posed this question during an hour-long presentation I gave to the World Bank in May 2015. The talk was on the use of remote sensing aerial robotics (UAVs) for disaster damage assessments; I used Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu and the double Nepal Earthquakes as case studies.

One advantage of aerial robotics over space robotics (satellites) is that the former can capture imagery at far higher spatial resolutions—sub 1-centimeter if need be. Without hesitation, a World Bank analyst in the conference room replied to my question: “Fifty centimeters.” I was taken aback by the rapid reply. Had I per chance missed something? Was it so obvious that 50 cm resolution was optimal? So I asked, “Why 50 centimeters?” Again, without hesitation: “Because that’s the resolution we’ve been using.” Ah ha! “But how do you know this is the optimal resolution if you haven’t tried 30 cm or even 10 cm?”

Lets go back to the fundamentals. We know that “rapid damage assessment is essential after disaster events, especially in densely built up urban areas where the assessment results provide guidance for rescue forces and other immediate relief efforts, as well as subsequent rehabilitation and reconstruction. Ground-based mapping is too slow, and typically hindered by disaster-related site access difficulties” (Gerke & Kerle 2011). Indeed, studies have shown that the inability of physically access damaged areas results in field teams underestimating the damage (Lemoine et al 2013). Hence one reason for the use of remote sensing.

We know that remote sensing can be used for two purposes following disasters. The first, “Rapid Mapping”, aims at providing impact assessments as quickly as possible after a disaster. The second, “Economic Mapping” assists in quantifying the economic impact of the damage. “Major distinctions between the two categories are timeliness, completeness and accuracies” (2013). In addition, Rapid Mapping aims to identify the relative severity of the damage (low, medium, high) rather than absolute damage figures. Results from Economic Mapping are combined with other geospatial data (building size, building type, etc) and economic parameters (e.g., cost per unit area, relocation costs, etc) to compute a total cost estimate (2013). The Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) is an example of Economic Mapping.

It is worth noting that a partially destroyed building may be seen as a complete economic loss, identical to a totally destroyed structure (2011). “From a casualty / fatality assessment perspective, however, a structure that is still partly standing […] offers a different survival potential” (2011).

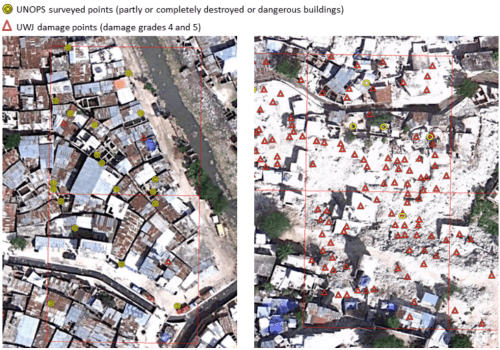

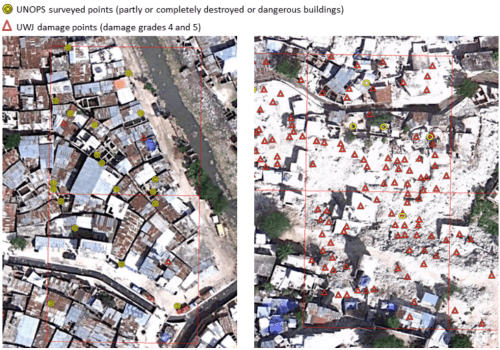

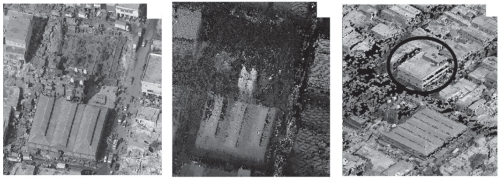

We also know that “damage detectability is primarily a function of image resolution” (2011). The Haiti Earthquake was “one of the first major disasters in which very high resolution satellite and airborne imagery was embraced to delineate the event impact (2013). It was also “the first time that the PDNA was based on damage assessment produced with remotely sensed data” (2013). Imagery analysis of the impact confirmed that a “moderate resolution increase from 41 cm to 15 cm has profound effects on damage mapping accuracy” (2011). Indeed, a number of validation studies carried out since 2010 have confirmed that “the higher detail airborne imagery performs much better [than lower resolution] satellite imagery” (2013). More specifically, the detection of very heavy damage and destruction in Haiti aerial imagery “is approximately a factor 8 greater than in the satellite imagery.”

Comparing the aerial imagery analysis with field surveys, Lemoine et al. find that “the number of heavily affected and damaged buildings in the aerial point set is slightly higher than that obtained from the field survey” (2013). The correlation between the results of the aerial imagery analysis and field surveys is sensitive to land-use (e.g., commercial, downtown, industrial, residential high density, shanty, etc). In highly populated areas such as shanty zones, “the over-estimation of building damage from aerial imagery could simply be a result of an incomplete field survey while, in downtown, where field surveys seem to have been conducted in a more systematic way, the damage assessment from aerial imagery matches very well the one obtained from the field” (2013).

In sum, the results from Haiti suggests that the “damage assessment from aerial imagery currently represents the best possible compromise between timeliness and accuracy” (2013). The Haiti case study also “showed that the damage derived from satellite imagery was underestimated by a factor of eight, compared to the damage derived from aerial imagery. These results suggest that despite the fast availability of very high resolution satellite imagery […], the spatial resolution of 50 cm is not sufficient for an accurate interpretation of building damage.”

In other words, even though “damage assessments depend very much on the timeliness of the aerial images acquisitions and requires a considerable effort of visual interpretation as an element of compromise; [aerial imagery] remains the best trade-of in terms of required quality and timeliness for producing detailed damage assessments over large affected areas compared to satellite based assessments (insufficient quality) and exhaustive field inventories (too slow).” But there’s a rub with respect to aerial imagery. While the above results do “show that the identification of building damage from aerial imagery […] provides a realistic estimate of the spatial pattern and intensity of damage,” the aerial imagery analysis still “suffers from several limitations due to the nadir imagery” (2013).

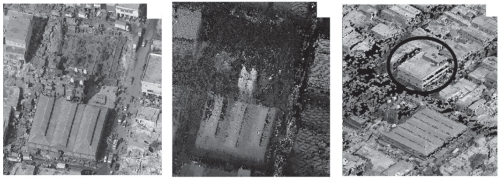

“Essentially all conventional airborne and spacebar image data are taken from a quasi-vertical perspective” (2011). Vertical (or nadir) imagery is particularly useful for a wide range of applications, for sure. But when it comes to damage mapping, vertical data have great limitations, particularly when concerning structural building damage (2011). While complete collapse can be readily identified using vertical imagery (e.g., disintegrated roof structures and associated high texture values, or adjacent rubble piles, etc), “lower levels of damage are much harder to map. This is because such damage effects are largely expressed along the façades, which are not visible in such imagery” (2011). According to Gerke and Kerle, aerial oblique imagery is more useful for disaster damage assessment than aerial or satellite imagery taken with a vertical angle. I elaborated on this point vis-a-vis a more recent study in this blog post.

Clearly, “much of the challenge in detecting damage stems from the complex nature of damage” (2011). For some types and sizes of damage, using only vertical (nadir) imagery will result in missed damage (2013). The question, therefore, is not simply one of spatial resolution but the angle at which the aerial or space-based image is taken, land-use and the type of damage that needs to be quantified. Still, we do have a partial answer to the first question. Technically, the optimal spatial resolution for disaster damage assessments is certainly not 50 cm since 15 cm proved far more useful in Haiti.

Of course, if higher-resolution imagery is not available in time (or at all), than clearly 50 cm imagery is infinitely more optimal than no imagery. In fact, even 5 meter imagery that is available within 24-48 hours of a disaster can add value if this imagery comes with baseline imagery, i.e., imagery of the location of interest before the disaster. Baseline data enables the use of automated change-detection algorithms that can provide a first estimate of damage severity and the location or scope of that severity. What’s more, these change-detection algorithms could automatically plot a series of waypoints to chart the flight plan of an autonomous aerial robot (UAV) to carry out closer inspection. In other words, satellite and aerial data can be complementary, and the drawbacks of low resolution imagery can be offset if said imagery is available at a higher temporal frequency.

On the flip side, just because the aerial imagery used in the Haiti study was captured at 15 cm resolution does not imply that 15 cm resolution is the most optimal spatial resolution for disaster damage. It could very well be 10 cm. This depends entirely on the statistical distribution of the size of damaged features (e.g, the size of a crack, a window, a tile, etc,), the local architecture (e.g., type of building materials used and so on) and the type of hazard (e.g, hurricane, earthquake, etc). That said, “individual indicators of destruction, such as a roof or façade damage, do not linearly add to a given damage class [e.g., low, medium, high]” (2011). This limitation is alas “fundamental in remote sensing where no assessment of internal structural integrity is possible” (2011).

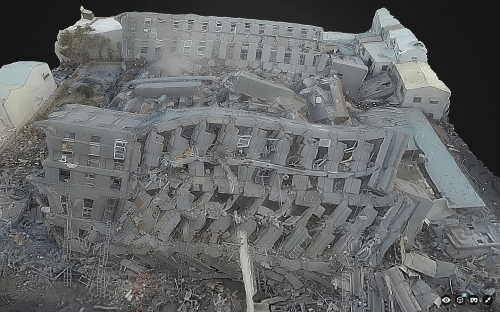

In any event, one point is certain: there was no need to capture aerial imagery (both nadir and obliques) at 5 centimeter resolution during the World Bank’s humanitarian UAV mission after Cyclone Pam—at least not for the purposes of 2D imagery analysis. This leads me to one final point. As recently noted during my opening Keynote at the 2016 International Drones and Robotics for Good Awards in Dubai, disaster damage is a 3D phenomenon, not a 2D experience. “Buildings are three-dimensional, and even the most detailed view at only one of those dimensions is ill-suited to describe the status of such features” (2011). In other words, we need “additional perspectives to provide a more comprehensive view” (2011).

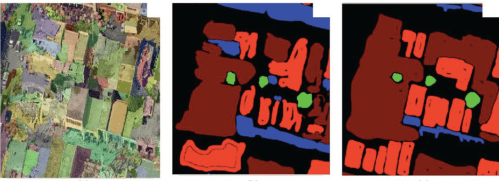

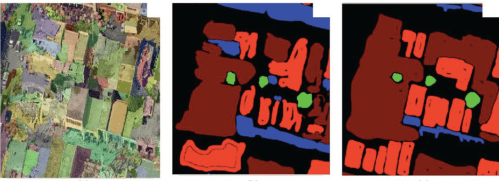

There are very few peer-reviewed scientific papers that evaluate the use of high-resolution 3D models for the purposes of damage assessments. This one is likely the most up-to-date study. An earlier research effort by Booth et al. found that the overall correlation between the results from field surveys and 3D analysis of disaster damage was “an encouraging 74 percent.” But this visual analysis was carried out manually, which could have introduced non-random errors. After all, “the subjectivity inherent in visual structure damage mapping is considerable” (2011). Could semi-automated methods for the analysis of 3D models thus yield a higher correlation? This is the research question posed by Gerke and Kerle in their 2011 study.

The authors tested this question using aerial imagery from the Haiti Earthquake. When 3D features were removed from their automated analysis, “classification performance declined, for example by some 10 percent for façades, the class that benefited most from the 3D derivates” (2011). The researchers also found that trained imagery analysts only agreed at most 76% of the time in their visual interpretation and assessments of aerial data. This is in part due to the lack of standards for damage categories (2011).

I made this point more bluntly in this earlier blog post. Just imagine when you have hundreds of professionals and/or digital volunteers analyzing imagery (e.g, through crowdsourcing) and no standardized categories of disaster damage to inform the consistent interpretation of said imagery. This collective subjectivity introduces a non-random error into the overall analysis. And because it is non-random, this error cannot be accounted for. In contrast, a more semi-automated solution would render this error more random, which means the overall model could potentially be adjusted accordingly.

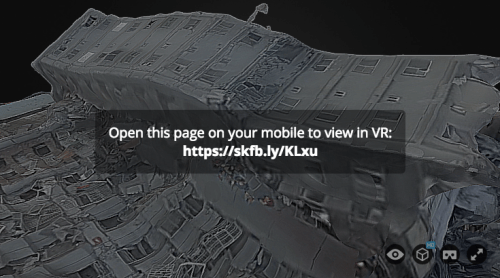

Gerke and Kerle conclude that high quality 3D models are “in principle well-suited for comprehensive semi-automated damage mapping. In particular façades, which are critical [to the assessment process], can be assessed [when] multiple views are provided.” That said, the methodology used by the authors was “still essentially based on projecting 3D data into 2D space, with conceptual and geometric limitations. [As such], one goal should be to perform the actual damage assessment and classification in 3D.” This explains why I’ve been advocating for Virtual Reality (VR) based solutions as described here.

Geek and Kerle also “required extensive training data and substantial subjective evidence integration in the final damage class assessment. This raises the question to what extent rules could be formulated to create a damage ontology as the basis for per-building damage scoring.” This explains why I invited the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) to create a damage ontology based on the aerial imagery from Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu. This ontology is based on 2D imagery, however. Ironically, very high spatial resolution 2D imagery can be more difficult to interpret than lower-res imagery since the high resolution imagery inevitably adds more “noise” to the data.

Ultimately, we’ll need to move on to 3D damage ontologies that can be visualized using VR headsets. 3D analysis is naturally more intuitive to us since we live in a mega-high resolution 3D world rather than a 2D one. As a result, I suspect there would be more agreement between different analysts studying dynamic, very high-resolution 3D models versus 2D static images at the same spatial res.

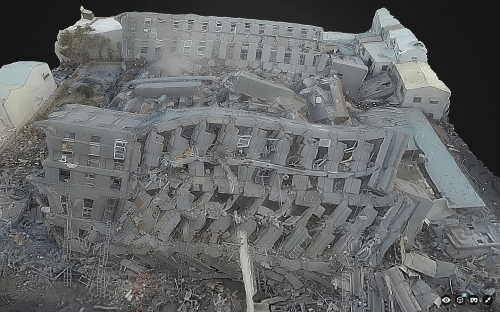

Taiwan’s National Cheng Kung University created this 3D model from aerial imagery captured by UAV. This model was created and uploaded to Sketchfab on the same day the earthquake struck. Note that Sketchfab recently added a VR feature to their platform, which I tried out on this model. Simply open this page on your mobile device to view the disaster damage in Taiwan in VR. I must say it works rather well, and even seems to be higher resolution in VR mode compared to the 2D projections of the 3D model above. More on the Taiwan model here.

But to be useful for disaster damage assessments, the VR headset would need to be combined with wearable technology that enables the end-user to digitally annotate (or draw on) the 3D models directly within the same VR environment. This would render the analysis process more intuitive while also producing 3D training data for the purposes of machine learning—and thus automated feature detection.

I’m still actively looking for a VR platform that will enable this, so please do get in touch if you know of any group, company, research institute, etc., that would be interested in piloting the 3D analysis of disaster damage from the Nepal Earthquake entirely within a VR solution. Thank you!