I have been writing and blogging about “information forensics” for a while now and thus relished Nieman Report’s must-read study on “Truth in the Age of Social Media.” My applied research has specifically been on the use of social media to support humanitarian crisis response (see the multiple links at the end of this blog post). More specifically, my focus has been on crowdsourcing and automating ways to quantify veracity in the social media space. One of the Research & Development projects I am spearheading at the Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) specifically focuses on this hybrid approach. I plan to blog about this research in the near future but for now wanted to share some of the gems in this superb 72-page Nieman Report.

In the opening piece of the report, Craig Silverman writes that “never before in the history of journalism—or society—have more people and organizations been engaged in fact checking and verification. Never has it been so easy to expose an error, check a fact, crowdsource and bring technology to bear in service of verification.” While social media is new, traditional journalistic skills and values are still highly relevant to verification challenges in the social media space. In fact, some argue that “the business of verifying and debunking content from the public relies far more on journalistic hunches than snazzy technology.”

I disagree. This is not an either/or challenge. Social computing can help every-one, not just journalists, develop and test hunches. Indeed, it is imperative that these tools be in the reach of the general public since a “public with the ability to spot a hoax website, verify a tweet, detect a faked photo, and evaluate sources of information is a more informed public. A public more resistant to untruths and so-called rumor bombs.” This public resistance to untruths can itself be moni-tored and modeled to quantify veracity, as this study shows.

David Turner from the BBC writes that “while some call this new specialization in journalism ‘information forensics,’ one does not need to be an IT expert or have special equipment to ask and answer the fundamental questions used to judge whether a scene is staged or not.” No doubt, but as Craig rightly points out, “the complexity of verifying content from myriad sources in various mediums and in real time is one of the great new challenges for the profession.” This is fundamentally a Social Computing, Crowd Computing and Big Data problem. Rumors and falsehoods are treated as bugs or patterns of interference rather than as a feature. The key here is to operate at the aggregate level for statistical purposes and to move beyond the notion of true/false as a dichotomy and to-wards probabilities (think statistical physics). Clustering social media across different media and cross-triangulation using statistical models is one area I find particularly promising.

Furthermore, the fundamental questions used to judge whether or not a scene is staged can be codified. “Old values and skills aren’t still at the core of the discipline.” Indeed, and heuristics based on decades of rich experience in the field of journalism can be coded into social computing algorithms and big data analytics platforms. This doesn’t mean that a fully automated solution should be the goal. The hunch of the expert when combined with the wisdom of the crowd and advanced social computing techniques is far more likely to be effective. As CNN’s Lila King writes, technology may not always be able to “prove if a story is reliable but offers helpful clues.” The quicker we can find those clues, the better.

It is true, as Craig notes, that repressive regimes “create fake videos and images and upload them to YouTube and other websites in the hope that news organizations and the public will find them and take them for real.” It is also true that civil society actors can debunk these falsifications as often I’ve noted in my research. While the report focuses on social media, we must not forget that off-line follow up and investigation is often an option. During the 2010 Egyptian Parliamentary Elections, civil society groups were able to verify 91% of crowd-sourced information in near real time thanks to hyper-local follow up and phone calls. (Incidentally, they worked with a seasoned journalist from Thomson Reuters to design their verification strategies). A similar verification strategy was employed vis-a-vis the atrocities commi-tted in Kyrgyzstan two years ago.

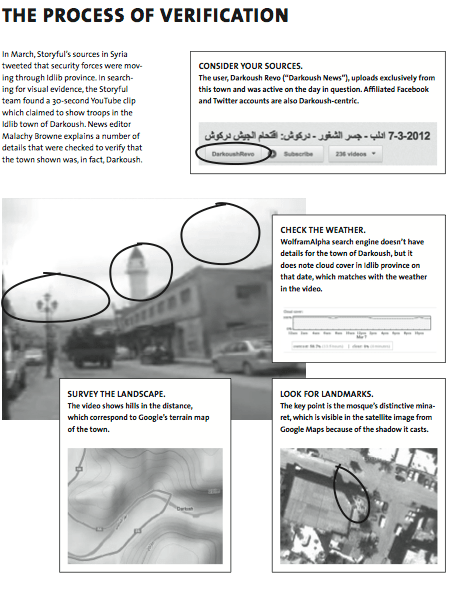

In his chapter on “Detecting Truth in Photos”, Santiago Lyon from the Associated Press (AP) describes the mounting challenges of identifying false or doctored images. “Like other news organizations, we try to verify as best we can that the images portray what they claim to portray. We look for elements that can support authenticity: Does the weather report say that it was sunny at the location that day? Do the shadows fall the right way considering the source of light? Is cloth- ing consistent with what people wear in that region? If we cannot communicate with the videographer or photographer, we will add a disclaimer that says the AP “is unable to independently verify the authenticity, content, location or date of this handout photo/video.”

Santiago and his colleagues are also exploring more automated solutions and believe that “manipulation-detection software will become more sophisticated and useful in the future. This technology, along with robust training and clear guidelines about what is acceptable, will enable media organizations to hold the line against willful image manipulation, thus maintaining their credibility and reputation as purveyors of the truth.”

David Turner’s piece on the BBC’s User-Generated Content (UGC) Hub is also full of gems. “The golden rule, say Hub veterans, is to get on the phone whoever has posted the material. Even the process of setting up the conversation can speak volumes about the source’s credibility: unless sources are activists living in a dictatorship who must remain anonymous.” This was one of the strategies used by Egyptians during the 2010 Parliamentary Elections. Interestingly, many of the anecdotes that David and Santiago share involve members of the “crowd” letting them know that certain information they’ve posted is in fact wrong. Technology could facilitate this process by distributing the challenge of collective debunking in a far more agile and rapid way using machine learning.

This may explain why David expects the field of “information forensics” to becoming industrialized. “By that, he means that some procedures are likely to be carried out simultaneously at the click of an icon. He also expects that technological improvements will make the automated checking of photos more effective. Useful online tools for this are Google’s advanced picture search or TinEye, which look for images similar to the photo copied into the search function.” In addition, the BBC’s UGC Hub uses Google Earth to “confirm that the features of the alleged location match the photo.” But these new technologies should not and won’t be limited to verifying content in only one media but rather across media. Multi-media verification is the way to go.

Journalists like David Turner often (and rightly) note that “being right is more important than being first.” But in humanitarian crises, information is the most perishable of commodities, and being last vis-a-vis information sharing can actual do harm. Indeed, bad information can have far-reaching negative con-sequences, but so can no information. This tradeoff must be weighed carefully in the context of verifying crowdsourced crisis information.

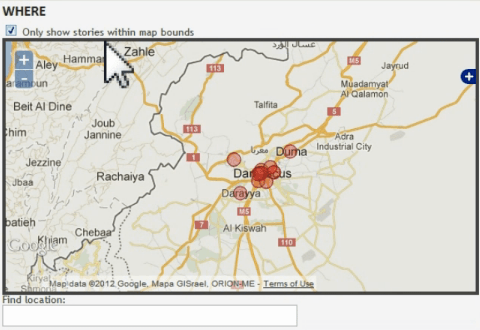

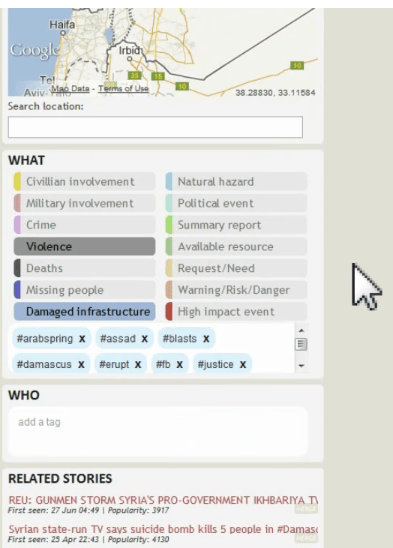

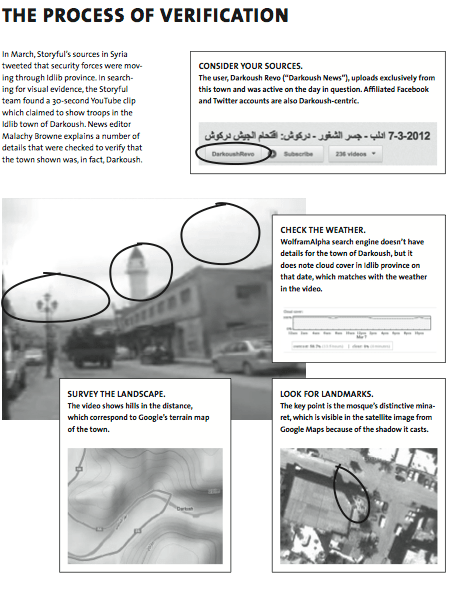

Mark Little’s chapter on “Finding the Wisdom in the Crowd” describes the approach that Storyful takes to verification. “At Storyful, we thinking a com-bination of automation and human skills provides the broadest solution.” Amen. Mark and his team use the phrase “human algorithm” to describe their approach (I use the term Crowd Computing). In age when every news event creates a community, “authority has been replaced by authenticity as the currency of social journalism.” Many of Storyful’s tactics for vetting authenticity are the same we use in crisis mapping when we seek to validate crowdsourced crisis information. These combine the common sense of an investigative journalist with advanced digital literacy.

In her chapter, “Taking on the Rumor Mill,” Katherine Lee rights that a “disaster is ready-made for social media tools, which provide the immediacy needed for reporting breaking news.” She describes the use of these tools during and after the tornado hat hit Alabama in April 2011. What I found particularly interesting was her news team’s decision to “log to probe some of the more persistent rumors, tracking where they might have originated and talking with officials to get the facts. The format fit the nature of the story well. Tracking the rumors, with their ever-changing details, in print would have been slow and awkward, and the blog allowed us to update quickly.” In addition, the blog format “gave readers a space to weigh in with their own evidence, which proved very useful.”

The remaining chapters in the Nieman Report are equally interesting but do not focus on “information forensics” per se. I look forward to sharing more on QCRI’s project on quantifying veracity in the near future as our objective is to learn from experts such as those cited above and codify their experience so we can leverage the latest breakthroughs in social computing and big data analytics to facilitate the verification and validation of crowdsourced social media content. It is worth emphasizing that these codified heuristics cannot and must not remain static, nor can the underlying algorithms become hardwired. More on this in a future post. In the meantime, the following links may be of interest:

- Information Forensics: Five Case Studies on How to Verify Crowdsourced Information from Social Media (Link)

- How to Verify and Counter Rumors in Social Media (Link)

- Data Mining to Verify Crowdsourced Information in Syria (Link)

- Analyzing the Veracity of Tweets During a Crisis (Link)

- Crowdsourcing for Human Rights: Challenges and Opportunities for Information Collection & Verification (Link)

- Truthiness as Probability: Moving Beyond the True or False Dichotomy when Verifying Social Media (Link)

- The Crowdsourcing Detective: Crisis, Deception and Intrigue in the Twittersphere (Link)

- Crowdsourcing Versus Putin (Link)

- Wiki on Truthiness resources (Link)

- My TEDx Talk: From Photosynth to ALLsynth (Link)

- Social Media and Life Cycle of Rumors during Crises (Link)

- Wag the Dog, or How Falsifying Crowdsourced Data Can Be a Pain (Link)