Buddhist Temples adorn Nepal’s blessed land. Their stupas, like Everest, stretch to the heavens, yearning to democratize the sky. We felt the same yearning after landing in Kathmandu with our UAVs. While some prefer the word “drone” over “UAVs”, the reason our Nepali partners use the latter dates back some 3,000 years to the spiritual epic Mahabharata (Great Story of Bharatas). The ancient story features Drona, a master of advanced military arts who slayed hundreds of thousands with his bow & arrows. This strong military connotation explains why our Nepali partners use “UAV” instead, which is the term we also used for our Humanitarian UAV Mission in the land of Buddha. Our purpose: to democratize the sky.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are aerial robots. They are the first wave of robotics to impact the humanitarian space. The mission of the Humanitarian UAV Network (UAViators) is to enable the safe, responsible and effective use of UAVs in a wide range of humanitarian and development settings. We thus spearheaded a unique and weeklong UAV Mission in Nepal in close collaboration with Kathmandu University (KU), Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL), DJI and Pix4D. This mission represents the first major milestone for Kathmandu Flying Labs (please see end of this post for background on KFL).

Our joint UAV mission combined both hands-on training and operational deployments. The full program is available here. The first day comprised a series of presentations on Humanitarian UAV Applications, Missions, Best Practices, Guidelines, Technologies, Software and Regulations. These talks were given by myself, KU, DJI, KLL and the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) of Nepal. The second day focused on direct hands-on training. DJI took the lead by training 30+ participants on how to use the Phantom 3 UAVs safely, responsibly. Pix4D, also on site, followed up by introducing their imagery-analysis software.

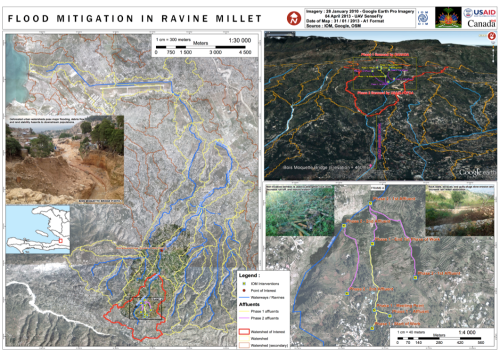

The second-half of the day was dedicated to operations. We had already received written permission from the CAA to carry out all UAV flights thanks to KU’s outstanding leadership. KU also selected the deployment sites and enabled us to team up with the very pro-active Community Disaster Management Committee (CDMC-9) of Kirtipur to survey the town of Panga, which had been severely affected by the earthquake just months earlier. The CDMC was particularly keen to gain access to very high-resolution aerial imagery of the area to build back faster and better, so we spent half-a-day flying half-a-dozen Phantom 3’s over parts of Panga as requested by our local partners.

The best part of this operation came at the end of the day when we had finished the mission and were packing up: Our Nepali partners politely noted that we had not in fact finished the job; we still had a lot more area to cover. They wanted us back in Panga the following day to complete our mapping mission. We thus changed our plans and returned the next day during which—thanks to DJI & Pix4D—we flew several dozen additional UAV flights from four different locations across Panga (without taking a single break; no lunch was had). Our local partners were of course absolutely invaluable throughout since they were the ones informing the flight plans. They also made it possible for us to launch and land all our flights from the highest rooftops across town. (Click images to enlarge).

Meanwhile, back at KU, our Pix4D partners provided hands-on training on how to use their software to analyze the aerial imagery we had collected the day before. KLL also provided training on how to use the Humanitarian Open Street Map Tasking Manager to trace this aerial imagery. Incidentally, we flew well over 60 UAV flights all in all over the course of our UAV mission, which includes all our training flights on campus as well as our aerial survey of a teaching hospital. Not a single incident or accident occurred; everyone followed safety guidelines and the technology worked flawlessly.

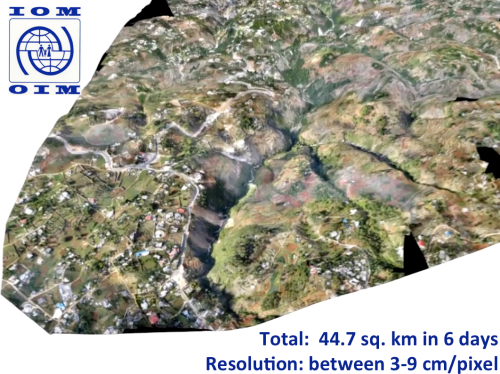

With more than 800 aerial photographs in hand, the Pix4D team worked through the night to produce a very high-resolution orthorectified mosaic of Panga. Here are some of the results.

Compare these results with the resolution and colors of the satellite imagery for the same area (maximum zoom).

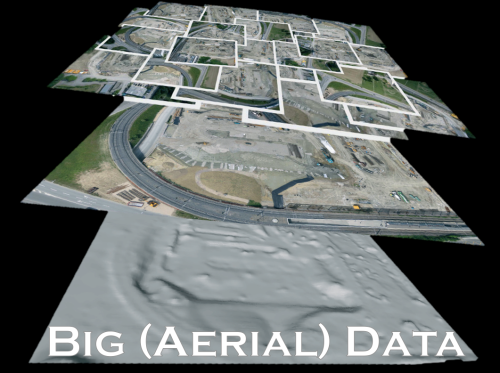

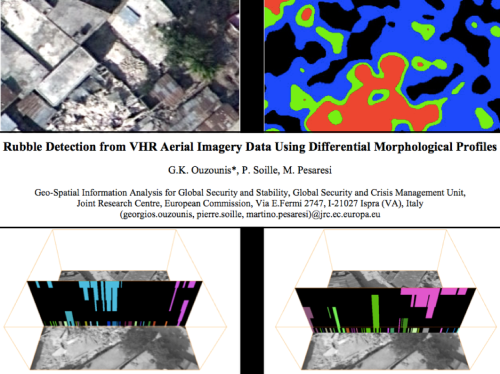

We can now use MicroMappers to crowdsource the analysis & digital annotation of oblique aerial pictures and videos collected throughout the mission. This is an important step in the development of automated feature-detection algorithms using techniques from computer vision and machine learning. The reason we want automated solutions is because aerial imagery already presents a Big Data challenge for humanitarian and development organizations. Indeed, a single 20- minute UAV flight can generate some 800 images. A trained analyst needs at least one minute to analyze a single image, which means that more than 13 hours of human time is needed to analyze imagery captured from just one 20-minute UAV flight. More on this Big Data challenge here.

Incidentally, since Pix4D also used their software to produce a number of stunning 3D models, I’m keen to explore ways to crowdsource 3D models via MicroMappers and to explore possible Virtual Reality solutions to the Big Data challenge. In any event, we generated all the aerial data requested by our local partners by the end of the day.

While this technically meant that we had successfully completed our mission, it didn’t feel finished to me. I really wanted to “liberate” the data completely and place it directly into the hands of the CDCM and local community in Panga. What’s the point of “open data” if most of Panga’s residents are not able to view or interact with the resulting maps? So I canceled my return flight and stayed an extra day to print out our aerial maps on very large roll-able and waterproof banners (which are more durable than paper-based maps).

We thus used these banner-maps and participatory mapping methods to engage the local community directly. We invited community members to annotate the very-high resolution aerial maps themselves by using tape and color-coded paper we had brought along. In other words, we used the aerial imagery as a base map to catalyze a community-wide discussion; to crowdsource and to visualize the community’s local knowledge. Participatory mapping and GIS (PPGIS) can play an impactful role in humanitarian and development projects, hence the initiative with our local partners (more here on community mapping).

In short, our humanitarian mission combined aerial robotics, computer vision, waterproof banners, tape, paper and crowdsourcing to inform the rebuilding process at the community level.

The engagement from the community was absolutely phenomenal and definitely for me the highlight of the mission. Our CDMC partners were equally thrilled and excited with the community engagement that the maps elicited. There were smiles all around. When we left Panga some four hours later, dozens of community members were still discussing the map, which our partners had hung up near a popular local teashop.

There’s so much more to share from this UAV mission; so many angles, side-stories and insights. The above is really just a brief and incomplete teaser. So stay tuned, there’s a lot more coming up from DJI and Pix4D. Also, the outstanding film crew that DJI invited along is already reviewing the vast volume of footage captured during the week. We’re excited to see the professionally edited video in coming weeks, not to mention the professional photographs that both DJI and Pix4D took throughout the mission. We’re especially keen to see what our trainees at KU and KLL do next with the technology and software that are now in their hands. Indeed, the entire point of our mission was to help build local capacity for UAV missions in Nepal by transferring knowledge, skills and technology. It is now their turn to democratize the skies of Nepal.

Acknowledgements: Some serious acknowledgements are in order. First, huge thanks to Lecturer Uma Shankar Panday from KU for co-sponsoring this mission, for hosting us and for making our joint efforts a resounding success. The warm welcome and kind hospitality we received from him, KU’s faculty and executive leadership was truly very touching. Second, special thanks to the CAA of Nepal for participating in our training and for giving us permission to fly. Third, big, big thanks to the entire DJI and Pix4D Teams for joining this UAViators mission and for all their very, very hard work throughout the week. Many thanks also to DJI for kindly donating 10 Smartisan phones and 10 Phantom 3’s to KU and KLL; and kind thanks to Pix4D for generously donating licenses of their software to both KU and KLL. Fourth, many thanks to KLL for contributing to the training and for sharing our vision behind Kathmandu Flying Labs. Fifth, I’d like to express my sincere gratitude to Smartisan for co-sponsoring this mission. Sixth, deepest thanks to CDMC and Dhulikhel Hospital for partnering with us on the ops side of the mission. Their commitment and life-saving work are truly inspiring. Seventh, special thanks to the film and photography crew for being so engaged throughout the mission; they were absolutely part of the team. In closing, I want to specifically thank my colleagues Andrew Schroeder from UAViators and Paul & William from DJI for all the heavy lifting they did to make this entire mission possible. On a final and personal note, I’ve made new friends for life as a result of this UAV mission, and for that I am infinitely grateful.

Kathmandu Flying Labs: My colleague Dr. Nama Budhathoki and I began discussing the potential role that small UAVs could play in his country in early 2014, well over a year-and-half before Nepal’s tragic earthquakes. Nama is the Director of Kathmandu Living Labs, a crack team of Digital Humanitarians whose hard work has been featured in The New York Times and the BBC. Nama and team create open-data maps for disaster risk reduction and response. They use Humanitarian OpenStreetMap’s Tasking Server to trace buildings and roads visible from orbiting satellites in order to produce these invaluable maps. Their primary source of satellite imagery for this is Bing. Alas, said imagery is both low-resolution and out-of-date. And they’re not sure they’ll have free access to said imagery indefinitely either.

So Nama and I decided to launch a UAV Innovation Lab in Nepal, which I’ve been referring to as Kathmandu Flying Labs. A year-and-a-half later, the tragic earthquake struck. So I reached out to DJI in my capacity as founder of the Humanitarian UAV Network (UAViators). The mission of UAViators is to enable the safe, responsible and effective use of UAVs in a wide range of humanitarian and development settings. DJI, who are on the Advisory Board of UAViators, had deployed a UAV team in response to the 6.1 earthquake in China the year before. Alas, they weren’t able to deploy to Nepal. But they very kindly donated two Phantom 2’s to KLL.

A few months later, my colleague Andrew Schroeder from UAViators and Direct Relief reconnected with DJI to explore the possibility of a post-disaster UAV Mission focused on recovery and rebuilding. Both DJI and Pix4D were game to make this mission happen, so I reached out to KLL and KU to discuss logistics. Professor Uma at KU worked tirelessly to set everything up. The rest, as they say, is history. There is of course a lot more to be done, which is why Nama, Uma and I are already planning the next important milestones for Kathmandu Flying Labs. Do please get in touch if you’d like to be involved and contribute to this truly unique initiative. We’re also exploring payload delivery options via UAVs and gearing up for new humanitarian UAV missions in other parts of the planet.