Disaster-affected communities are increasingly becoming “digital” communities. That is, they increasingly use mobile technology & social media to communicate during crises. I often refer to this user-generated content as Big (Crisis) Data. Humanitarian crisis computing seeks to rapidly identify informative, actionable and credible content in this growing stack of real-time information. The challenge is akin to finding the proverbial needle in the haystack since the vast majority of reports posted on social media is often not relevant for humanitarian response. This is largely a result of the demand versus supply problem described here.

In any event, the few “needles” of information that are relevant, can relay information that is vital and indeed-life saving for relief efforts—both traditional top-down efforts and more bottom-up grassroots efforts. When disaster strikes, we increasingly see social media traffic explode. We know there are important “pins” of relevant information hidden in this growing stack of information but how do we find them in real-time?

Humanitarian organizations are ill-equipped to managing the deluge of Big Crisis Data. They tend to sift through the stack of information manually, which means they aren’t able to process more than a small volume of information. This is represented by the dotted green line in the picture below. Big Data is often described as filter failure. Our manual filters cannot manage the large volume, velocity and variety of information posted on social media during disasters. So all the information above the dotted line, Big Data, is completely ignored.

This is where Advanced Computing comes in. Advanced Computing uses Human and Machine Computing to manage Big Data and reduce filter failure, thus allowing humanitarian organizations to process a larger volume, velocity and variety of crisis information in less time. In other words, Advanced Computing helps us push the dotted green line up the information stack.

In the early days of digital humanitarian response, we used crowdsourcing to search through the haystack of user-generated content posted during disasters. Note that said content can also include text messages (SMS), like in Haiti. Crowd-sourcing crisis information is not as much fun as the picture below would suggest, however. In fact, crowdsourcing crisis information was (and can still be) quite a mess and a big pain in the haystack. Needless to say, crowdsourcing is not the best filter to make sense of Big Crisis Data.

Recently, digital humanitarians have turned to microtasking crisis information as described here and here. The UK Guardian and Wired have also written about this novel shift from crowdsourcing to microtasking.

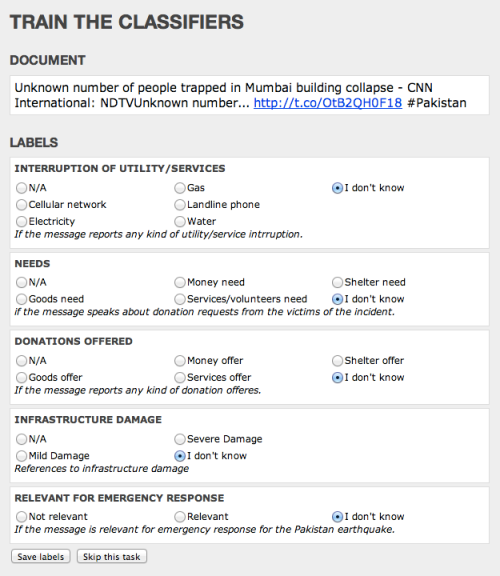

Microtasking basically turns a haystack into little blocks of stacks. Each micro-stack is then processed by one ore more digital humanitarian volunteers. Unlike crowdsourcing, a microtasking approach to filtering crisis information is highly scalable, which is why we recently launched MicroMappers.

The smaller the micro-stack, the easier the tasks and the faster that they can be carried out by a greater number of volunteers. For example, instead of having 10 people classify 10,000 tweets based on the Cluster System, microtasking makes it very easy for 1,000 people to classify 10 tweets each. The former would take hours while the latter mere minutes. In response to the recent earthquake in Pakistan, some 100 volunteers used MicroMappers to classify 30,000+ tweets in about 30 hours, for example.

Machine Computing, in contrast, uses natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML) to “quantify” the haystack of user-generated content posted on social media during disasters. This enable us to automatically identify relevant “needles” of information.

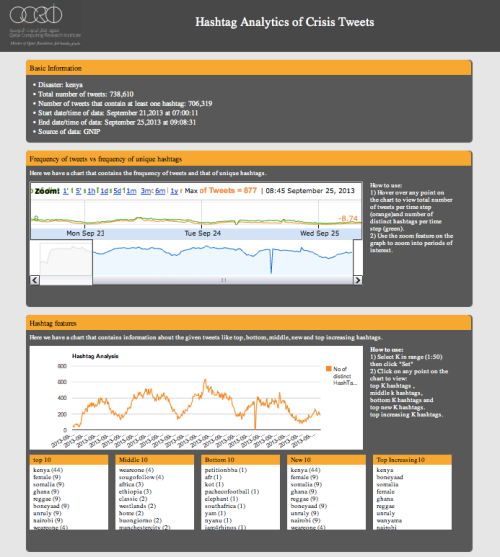

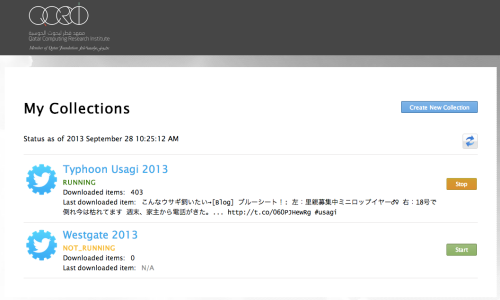

An example of a Machine Learning approach to crisis computing is the Artificial Intelligence for Disaster Response (AIDR) platform. Using AIDR, users can teach the platform to automatically identify relevant information from Twitter during disasters. For example, AIDR can be used to automatically identify individual tweets that relay urgent needs from a haystack of millions of tweets.

The pictures above are taken from the slide deck I put together for a keynote address I recently gave at the Canadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.