Unlike analog information, “digital information inherently leaves a trace that can be analyzed (in real-time or later on).” But the “crux of the ‘Big Data’ paradigm is actually not the increasingly large amount of data itself, but its analysis for intelligent decision-making (in this sense, the term ‘Big Data Analysis’ would actually be more fitting than the term ‘Big Data’ by itself).” Martin Hilbert describes this as the “natural next step in the evolution from the ‘Information Age’ & ‘Information Societies’ to ‘Knowledge Societies’ […].”

Hilbert has just published this study on the prospects of Big Data for inter-national development. “From a macro-perspective, it is expected that Big Data informed decision-making will have a similar positive effect on efficiency and productivity as ICT have had during the recent decade.” Hilbert references a 2011 study that concluded the following: “firms that adopted Big Data Analysis have output and productivity that is 5–6 % higher than what would be expected given their other investments and information technology usage.” Can these efficiency gains be brought to the unruly world of international development?

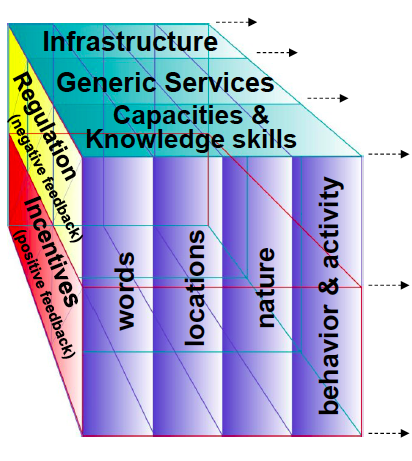

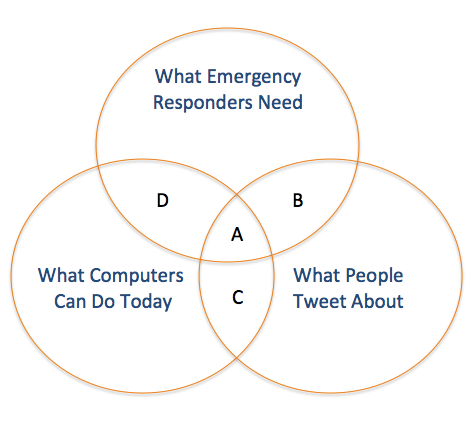

To answer this question, Hilbert introduces the above conceptual framework to “systematically review literature and empirical evidence related to the pre-requisites, opportunities and threats of Big Data Analysis for international development.” Words, Locations, Nature and Behavior are types of data that are becoming increasingly available in large volumes.

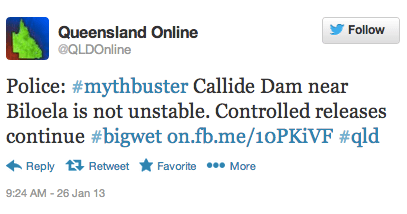

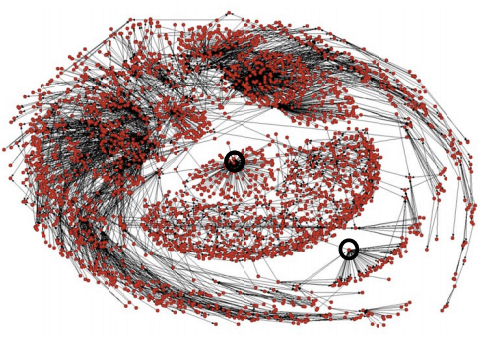

“Analyzing comments, searches or online posts [i.e., Words] can produce nearly the same results for statistical inference as household surveys and polls.” For example, “the simple number of Google searches for the word ‘unemployment’ in the U.S. correlates very closely with actual unemployment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Hilbert argues that the tremendous volume of free textual data makes “the work and time-intensive need for statistical sampling seem almost obsolete.” But while the “large amount of data makes the sampling error irrelevant, this does not automatically make the sample representative.”

The increasing availability of Location data (via GPS-enabled mobile phones or RFIDs) needs no further explanation. Nature refers to data on natural processes such as temperature and rainfall. Behavior denotes activities that can be captured through digital means, such as user-behavior in multiplayer online games or economic affairs, for example. But “studying digital traces might not automatically give us insights into offline dynamics. Besides these biases in the source, the data-cleaning process of unstructured Big Data frequently introduces additional subjectivity.”

The availability and analysis of Big Data is obviously limited in areas with scant access to tangible hardware infrastructure. This corresponds to the “Infra-structure” variable in Hilbert’s framework. “Generic Services” refers to the production, adoption and adaptation of software products, since these are a “key ingredient for a thriving Big Data environment.” In addition, the exploitation of Big Data also requires “data-savvy managers and analysts and deep analytical talent, as well as capabilities in machine learning and computer science.” This corresponds to “Capacities and Knowledge Skills” in the framework.

The third and final side of the framework represents the types of policies that are necessary to actualize the potential of Big Data for international develop-ment. These policies are divided into those that elicit a Positive Feedback Loops such as financial incentives and those that create regulations such as interoperability, that is, Negative Feedback Loops.

The added value of Big Data Analytics is also dependent on the availability of publicly accessible data, i.e., Open Data. Hilbert estimates that a quarter of US government data could be used for Big Data Analysis if it were made available to the public. There is a clear return on investment in opening up this data. On average, governments with “more than 500 publicly available databases on their open data online portals have 2.5 times the per capita income, and 1.5 times more perceived transparency than their counterparts with less than 500 public databases.” The direction of “causality” here is questionable, however.

Hilbert concludes with a warning. The Big Data paradigm “inevitably creates a new dimension of the digital divide: a divide in the capacity to place the analytic treatment of data at the forefront of informed decision-making. This divide does not only refer to the availability of information, but to intelligent decision-making and therefore to a divide in (data-based) knowledge.” While the advent of Big Data Analysis is certainly not a panacea,”in a world where we desperately need further insights into development dynamics, Big Data Analysis can be an important tool to contribute to our understanding of and improve our contributions to manifold development challenges.”

I am troubled by the study’s assumption that we live in a Newtonian world of decision-making in which for every action there is an automatic equal and opposite reaction. The fact of the matter is that the vast majority of development policies and decisions are not based on empirical evidence. Indeed, rigorous evidence-based policy-making and interventions are still very much the exception rather than the rule in international development. Why? “Account-ability is often the unhappy byproduct rather than desirable outcome of innovative analytics. Greater accountability makes people nervous” (Harvard 2013). Moreover, response is always political. But Big Data Analysis runs the risk de-politicize a problem. As Alex de Waal noted over 15 years ago, “one universal tendency stands out: technical solutions are promoted at the expense of political ones.” I hinted at this concern when I first blogged about the UN Global Pulse back in 2009.

In sum, James Scott (one of my heroes) puts it best in his latest book:

“Applying scientific laws and quantitative measurement to most social problems would, modernists believed, eliminate the sterile debates once the ‘facts’ were known. […] There are, on this account, facts (usually numerical) that require no interpretation. Reliance on such facts should reduce the destructive play of narratives, sentiment, prejudices, habits, hyperbole and emotion generally in public life. […] Both the passions and the interests would be replaced by neutral, technical judgment. […] This aspiration was seen as a new ‘civilizing project.’ The reformist, cerebral Progressives in early twentieth-century American and, oddly enough, Lenin as well believed that objective scientific knowledge would allow the ‘administration of things’ to largely replace politics. Their gospel of efficiency, technical training and engineering solutions implied a world directed by a trained, rational, and professional managerial elite. […].”

“Beneath this appearance, of course, cost-benefit analysis is deeply political. Its politics are buried deep in the techniques […] how to measure it, in what scale to use, […] in how observations are translated into numerical values, and in how these numerical values are used in decision making. While fending off charges of bias or favoritism, such techniques […] succeed brilliantly in entrenching a political agenda at the level of procedures and conventions of calculation that is doubly opaque and inaccessible. […] Charged with bias, the official can claim, with some truth, that ‘I am just cranking the handle” of a nonpolitical decision-making machine.”

See also: